The humanities: Looking back and looking ahead

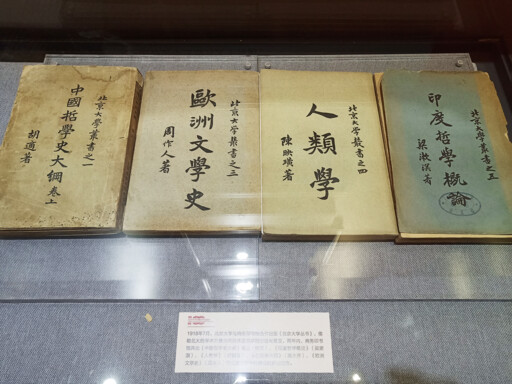

In July 1918, Peking University, in collaboration with the Commercial Press, launched a book series titled “Peking University Series,” aiming to promote the introduction and dissemination of Western learning through the university’s academic resources. Photo: TUCHONG

Although China has nurtured a deep humanistic tradition for millennia, the humanities as an institutionalized field of study are a relatively recent creation of the 20th century. The disciplinary structure of Chinese universities did not evolve directly from the classical taxonomy of knowledge but was deeply influenced by academic models originating in Europe and the United States. This article examines the historical preconditions for the emergence of modern humanities in China and the challenges they face in the contemporary context—for instance, how to reflect on the relationship between the humanities and diverse humanistic traditions, and how to redefine the mission of the humanities in the 21st century.

Classification of knowledge, birth of Chinese humanities

China has long cultivated a rich and continuous humanistic tradition, yet the classificatory principles of classical learning differ fundamentally from those of the modern academic system. Except for a few areas, early forms of knowledge organization cannot easily be categorized into what we now call “disciplines.” Within the framework of classical scholarship, no theoretical presupposition sharply separated the natural sciences from the humanities. The concept of “the humanities” as we understand it today is a modern construct. It was only in the 20th century that the term “humanities” came to be systematically rendered into Chinese as renwen xueke.

Although core humanistic fields such as literature, history, and philosophy had long taken shape in China, there was no clear distinction between the humanities and the social sciences for much of the modern era. The tripartite division of knowledge into the natural sciences, social sciences, and humanities only stabilized in the post–Cold War period. Since their inception, Chinese humanities have displayed a persistent dual tendency across all fields—literature, history, philosophy, and beyond: a trend toward the globalization (or Westernization) of disciplines and norms, and a countervailing effort to assert the autonomy of Chinese humanistic scholarship. The former is reflected in disciplinary classification, institutional structure, theoretical frameworks, methods, terminology, and the continual renewal of academic trends; the latter, in the movement to reconnect contemporary scholarship with classical traditions by re-examining methods, concepts, and perspectives, and in the recurrent reappearance of categories once superseded by early modern humanistic thought—such as jingxue (Chinese classical studies), guoxue (national learning), and certain forms of religious knowledge.

Over the past three decades, this dual tendency has become increasingly pronounced. On the one hand, disciplinary globalization—indeed, Americanization—has intensified through the state-driven campaign to build “world-class universities” in China, large-scale recruitment of overseas talent, and a growing alignment of scholarly standards with Western academia. On the other hand, many scholars have sought to reconnect modern research with the intellectual traditions of both classical and modern China, thereby re-establishing a culturally grounded sense of identity for Chinese humanistic scholarship.

A clear rupture separates the classificatory principles of classical scholarship from those of the modern humanities—each representing a distinct system of rules shaped by different historical contexts. Chinese systems of knowledge classification differ from those of modern Europe in origin and function, bearing a stronger resemblance to bibliographic cataloguing. Since the late Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), as large-scale translation and introduction of Western learning took place, Chinese intellectuals began to reassess traditional knowledge in light of Western categories and methods.

Given that classical Chinese learning centered on ancient texts and their taxonomic organization, it was possible—according to the standards of European humanism—to subsume this body of knowledge under the general rubric of the humanities. In practice, this knowledge was indeed reclassified and reorganized according to modern disciplinary principles and methodologies, thereby constructing a continuous and universally applicable genealogy of the humanities. The subjects, themes, and methods encompassed by humanistic study are now immensely diverse, yet from the outset, the birth of the modern Chinese university and its humanities was closely linked to national destiny and the encounter between Eastern and Western civilizations—persistently animated by questions such as: Why did China fall behind and suffer humiliation? Why did the West achieve prosperity and power? What are the essential differences between Chinese and Western civilizations?

Mutual inspiration between the humanities and intellectual movements

Modern Chinese humanities emerged through the continual interaction between intellectual movements and institutional reforms. Taking the humanities at Peking University and Tsinghua University in the 1920s as examples, whether radical or conservative in orientation, their leading figures were largely drawn from the two generations that had participated in the Revolution of 1911, the May Fourth Movement, and the New Culture Movement. These scholars either sought to “collate and systematize the national heritage” (zhengli guogu) through scientific methods or endeavored to rediscover the contemporary significance of classical traditions from a new historical perspective—what came to be known as “New Humanism” or “New Classicism.” Through these efforts, literature, philosophy, and history were re-established as the core disciplines of the humanities. In this sense, although the humanities developed their own internal trajectory, their evolution cannot be understood apart from the mutual stimulation between academic inquiry and broader intellectual and political movements.

From the 1980s—when old norms were overturned—to the 1990s, when new norms took shape, humanistic scholars played an especially vital role. The 1980s ended amid profound transformations in both China and the world. Although the momentum of that decade did not entirely vanish in the wake of the Cold War’s end (1989–1991), the historical shift was undeniable. From the early 1990s onward, the humanities and social sciences exhibited two concurrent trends: an increasingly globalized academic movement in terms of norms and standards, and a continuing intellectual effort to explore the distinctiveness and indigenization of Chinese scholarship.

Among the new disciplines that arose after the 1990s, guoxue became particularly prominent. Its revival, along with the re-establishment of research institutes devoted to it—at Peking University, Tsinghua University, Renmin University of China, and elsewhere—now stand as hallmarks of contemporary Chinese humanities. The question “What is guoxue?” has evolved from a binary reflection on the relationship between Chinese and Western learning into a broader inquiry into the relations between Confucian-centered classical knowledge and the cultural traditions and epistemologies of China’s many ethnic groups. Amid the identity crises produced by globalization and its counter-movements, this line of inquiry reveals one of the central questions facing the contemporary Chinese humanities: How should we reimagine China? What is “China’s world,” and what is “the world’s China”?

Challenges facing the humanities

The establishment of modern humanities rests on several important premises, yet in the contemporary context, these premises are faced with fundamental challenges.

First, modern humanistic knowledge established its foundation by breaking away from and critically re-evaluating the Confucian classical tradition. Broadly speaking, the humanities came to embody post-theological or post-jingxue values. How, then, should we understand the relationship between modern humanistic knowledge and the renewed vitality of classical and religious learning amid contemporary revivals?

Second, the humanities emerged within the matrix of modern science and its differentiated branches, yet their claim to autonomy rested on a methodological distinction from the sciences. As artificial intelligence and genetic technology transform both the production of knowledge and the conditions of human existence, to what extent does this claim to autonomy preserve the dignity and vitality of the humanities—and to what extent does it confine them to the limited sphere of human life? How might the humanities draw sustenance from scientific development while maintaining a critical distance from it?

Third, the tripartite classification of literature, history, and philosophy is derived directly from European systems of knowledge. Although it bears traces of continuity with traditional Chinese learning, structurally it is entirely different. How might we reconsider the meanings of these knowledge formations and classificatory systems across different cultural and regional contexts?

Fourth, the early formation of humanistic knowledge in China is closely related to successive cultural movements driven by the new intellectual strata that emerged on the historical stage in the late 19th century. The cultural movements of the 1980s and the intellectual debates of the 1990s similarly paved the way for the evolution of the contemporary humanities. As broad-based intellectual movements have waned today, how can the humanities and humanistic education again become sources of new ideas? How might the “intellectual sphere” be reshaped amid professionalization, marketization, and the pervasive influence of media?

Fifth, the development of transportation, the internet, and other information technologies has greatly enhanced the circulation and interaction of cultures. The classical norms of the modern humanities were established with reference to European and American models. Under present conditions, it is not enough to re-examine the premises of the humanities solely within their own historical lineage. The task also involves expanding the boundaries of the humanities, enriching their cultural and historical substance, and transcending both outdated Eurocentrism and various forms of self-centeredness. Only in this way can we foster a vibrant humanistic field that enhances sensitivity to and understanding of cultural diversity.

The contemporary world is experiencing profound crises within the multiple orders established after World War II. Yet it is precisely amid these challenges that the humanities may find new vitality. Within China’s great tradition, a deep consciousness of crisis has long served as an inner driving force for cultural renewal and development. The future of Chinese humanities is already present in our ongoing inquiries into the past and the present.

Wang Hui is a professor from the School of Humanities at Tsinghua University. This article has been edited and excerpted from Open Times, Issue 3, 2025.

Editor:Yu Hui

Copyright©2023 CSSN All Rights Reserved