Dream of the Red Chamber reconstructed through modern screen adaptations

FILE PHOTO: A 2017 series, featuring an all-child cast, focusing on the story “Granny Liu Visits the Grand View Garden”

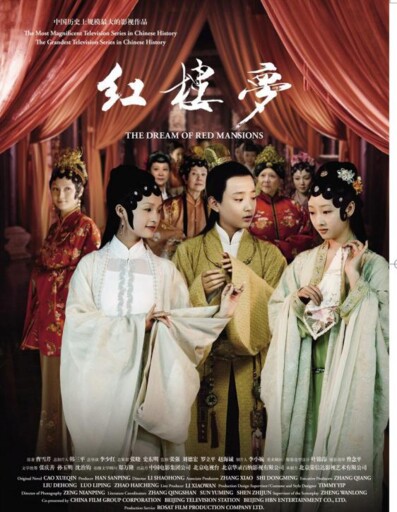

FILE PHOTO: A 2010 TV series based on the novel

FILE PHOTO: The 1987 TV series “Dream of the Red Chamber”

As an outstanding representative of classical Chinese literature, Dream of the Red Chamber pioneered cross-media creation as early as the era of the Zhiyanzhai annotated edition. From the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911) opera “Legend of Dream of the Red Chamber” to the modern dramas of the Republican era (1912–49), and from 20th-century spoken drama, Yueju opera, and Kunqu opera to contemporary stage and screen adaptations, these cross-media recreations bear vivid witness to the creative transformation and innovative development of China’s fine traditional culture. Among the many forms of adaptation, film and television—by virtue of their visual immediacy and wide reach—have become a primary means through which modern audiences encounter this classic. Whether through rigorous historical reconstruction, bold reinterpretation, or playful deconstruction, these works continually rewrite the tragic motif of “shared sorrow among countless beauties,” together forming a diverse, interwoven cinematic universe of the “Red Chamber.”

Classic interpretation of the 1987 TV series

The 1987 CCTV television series “Dream of the Red Chamber” remains both faithful to the original and creatively transformative. The episodes based on the novel’s first 80 chapters closely follow the original text, while those of the latter 40 boldly reimagine the ending. The early episodes preserve the novel’s narrative structure almost intact, whereas the final ones abandon Gao E’s continuation, instead drawing on the Zhiyanzhai commentary and the latest redology research of the time to reimagine the tragic finale of “leaving behind a vast, barren land, clean and empty.” This approach to adapting the work reflected the producers’ scholarly courage.

Visually, the series achieved a systematic act of cultural archaeology. With renowned writer Shen Congwen serving as consultant, the costume design drew inspiration from classical paintings to reconstruct the aristocratic dress code—mainly in Song (960–1279) and Ming (1368–1644) styles with selective Qing elements—so that color palettes subtly echoed each character’s temperament and fate. The production team scouted real historical gardens across China and, under the guidance of experts in garden design and ancient architecture, realistically recreated the Grand View Garden and major ceremonial scenes such as the imperial visit.

In character portrayal, Lin Daiyu’s poetic temperament was conveyed through subtle “dewy eyes” and “mist-wreathed brows” makeup and a restrained performance, while Wang Xifeng’s commanding personality was vividly expressed through her dramatic entrance—“her voice heard before her presence seen.” The soundtrack integrated classical poetry with modern musical composition: “Vain Longing” combined Kunqu tonal patterns with modern harmonies, and “Flower Burial Chant” adopted distinctive musical structures to echo traditional poetic rhythm. The enduring value of this adaptation lies in how it set a model for screen versions that both honor and reinterpret literary classics, demonstrating that the key to recreating a masterpiece is creative transformation grounded in deep understanding of its spiritual essence.

Modern attempt of the 2010 TV version

With the rapid rise of consumer culture, the boundary between high art and popular culture has increasingly blurred, and film and television have become a vital part of popular aesthetic life. It was in this context that Li Shaohong’s 2010 adaptation of Dream of the Red Chamber emerged—a boldly subversive reconstruction of the literary classic. This version restores narrative elements absent from the 1987 series, such as the “Illusory Land of Great Void,” and adopts a “complete presentation” approach covering all 120 chapters of the novel, including Gao E’s long-debated continuation. In pursuit of narrative completeness, the series employs a modern cinematic language of “voice-over narration plus fast cuts.” Quick scene transitions and extensive off-screen narration accelerate the plot, enhancing narrative efficiency but simultaneously diminishing the subtle, lingering charm of the original text. Some changes, however, proved to be missteps—most notably the controversial “Daiyu’s naked death” scene, an excessive interpretation that seeks visual shock at the expense of the traditional aesthetic spirit. Visually, the series integrates elements of Kunqu opera facial makeup into character design, attempting to create a surreal, dreamlike theatrical effect, though the results fell short. The use of soft focus and somber tones further intensify the dreamlike atmosphere, yet the overall sense of gloom and eeriness undermines the Grand View Garden’s intended vitality and poetic grace.

Cinematization and derivative works of the novel

In recent years, screen adaptations of the novel have exhibited increasing diversity, highlighting the enduring vitality of this classic IP in the digital era. The 12-episode series “Dream of the Red Chamber of Child Actors—Granny Liu Visits the Grand View Garden” (2017), created as an homage to the 1987 version, took an innovative approach by featuring an all-child cast. The young actors’ clear, articulate diction and proper etiquette imbue the production with a distinctive sense of childlike innocence. The series downplays the romance between Jia Baoyu and Lin Daiyu, centering instead on the storyline of “Granny Liu’s Visit to the Grand View Garden,” while retaining classic scenes such as “Baoyu and Daiyu’s First Meeting.” The creators placed particular emphasis on the inheritance and promotion of fine traditional Chinese culture—costumes, props, and ceremonial details were all designed with scholarly precision to faithfully recreate the atmosphere of the original novel. As a result, this adaptation serves as an ideal introduction for young audiences to engage with the novel.

Hu Mei’s 2024 film “Dream of the Red Chamber: The Love of Gold and Jade” seeks to reinterpret the classic from a youthful, commercialized modern perspective, aiming to guide the internet-native generation back to the literary original through cinema. Following this reconstructive logic, the film extracts the “Baoyu–Daiyu–Baochai” love triangle as its main narrative thread, employing a nonlinear storytelling structure to connect major scenes such as “Daiyu Burying the Flowers,” intensifying emotional conflicts and dramatic tension to cater to audience tastes. Yet the novel’s complex and profound social critique is reduced to a story of “the Jia family plots for Lin’s wealth” and youthful love’s pain. This tendency toward “lightening the heaviness” and “short-dramatization” inevitably dilutes the original’s intellectual depth. Moreover, the film’s chaotic timeline, mixed dialogic forms, and pursuit of heightened sensuality—seen in the over-dramatization of Baoyu and Daiyu’s passionate scenes and the newly invented subplot in which Wang Xifeng and Jia Lian conspire to seize the Lin family’s fortune—severely distort the spirit of the original work and undermine its subtle, restrained aesthetic.

In recent years, a number of film and television adaptations based on online novels have reinterpreted Dream of the Red Chamber through the creative appropriation of its motifs—mimicking its narrative segments, transforming its classical allusions, and borrowing or reassembling its dialogue. This strategy of “adaptive transformation” reconstructs the original text in contemporary cultural forms. For instance, “Joy of Life” portrays its protagonist Fan Xian as an ardent admirer of Dream of the Red Chamber. After being transported into an alternate historical world, Fan Xian—armed with his modern-day memories—reproduces the novel from memory, allowing it to circulate in the fictional realm and creating a “play-within-a-play” metaphorical structure. Meanwhile, recreation works on platforms like Bilibili and Douyin (Chinese version of TikTok) showcase the younger generation’s personalized interpretations of the classic. Through humor and sharp wit, they deconstruct iconic scenes, offering new and diverse reinterpretations. Although some verge on over-entertainment, their use of contemporary expression enables traditional Chinese culture to shine anew in modern times.

Balancing faithfulness and innovation

The enduring value of a literary classic lies in its capacity for continual rediscovery. The timelessness of Dream of the Red Chamber resides in the wisdom and philosophy of “seeing through the ways of the world,” in its vivid portrayal of humanity behind “pages full of absurd words,” and in the linguistic brilliance refined through “ten years of writing and multiple rounds of revision.” Therefore, any adaptation of such a classic must be grounded in a deep understanding of the original’s spiritual essence—approaching it with reverence to safeguard the cultural roots it embodies, and with creativity to awaken its resonance in a new era.

Looking back on the novel’s screen adaptations, creators have consistently sought to resolve two enduring challenges: how to strike a balance between fidelity to the novel’s spirit and the demands of audiovisual media, and how to achieve a creative synthesis of traditional aesthetics with modern sensibilities. From research-based restoration to deconstructive experimentation, from operatic conventions to animation, each reconstruction constitutes a cross-temporal dialogue between new artistic languages and the classic text. These adaptations reflect evolving Chinese aesthetic preferences, technological progress, and cultural values, reminding us that adaptation is never simple imitation but a demanding process of reconstruction—at once an homage to the classic and a profound reinterpretation that breathes new life into it. In the digital-intelligence era, fast-paced narrative editing may better suit contemporary viewing habits, but the novel’s lingering charm and delicate psychological portrayals still deserve preservation. Experimental visual styles can enhance artistic expressiveness, but must never come at the cost of sacrificing character authenticity or emotional logic.

Gu Shubo is an associate professor from the School of Humanities at Communication University of China.

Copyright©2023 CSSN All Rights Reserved