Seeking truth from facts: Guo Moruo’s academic tradition

FILE PHOTO: Guo Moruo, celebrated Chinese writer, historian, and archaeologist

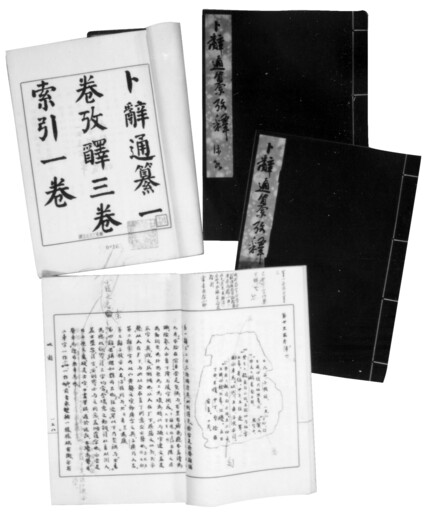

FILE PHOTO: A Comprehensive Compilation of Oracle Bone Inscriptions written by Guo Moruo

Seeking truth from facts is a longstanding principle of Marxist historiography and Chinese scholarship. Guo Moruo (1892–1978), the celebrated writer, historian, and archaeologist, attached particular importance to this principle: “Anyone who is able to seek truth from facts will, in terms of stance, viewpoint, and method, inevitably draw closer to Marxism-Leninism until they finally converge.” Throughout his more than fifty-year academic career, Guo consistently upheld this approach and made pioneering and significant contributions across many fields.

Comprehensive collection of historical materials

Adhering to “seeking truth from facts” requires research to be firmly grounded in solid historical evidence. Guo placed great emphasis on historical materials: “The study of history, like the study of any other discipline, does not allow for recklessness. It is of primary importance to grasp a correct and scientific historical outlook—this is a prerequisite. However, even with the correct outlook, if there is no rich and accurate material, or if the chronology of the material is unclear, then no correct conclusion can be drawn.”

In the Editorial Foreword to the inaugural issue of Historical Research, Guo explained the editorial approach to contributions: “If there are friends who have already mastered the application of Marxism-Leninism and are able to ‘conduct concrete analysis based on detailed materials,’ thereby producing ‘theoretical conclusions,’ then such friends and their works are, of course, most welcome. But even if, for the time being, one cannot reach ‘theoretical conclusions,’ as long as one can ‘conduct concrete analysis based on detailed materials,’ or even simply provide ‘detailed materials’ or newly discovered sources, all these are equally welcomed by us. Any research must first be based on acquiring as many materials as can be accessed, then on concrete analysis, and then on drawing conclusions. As long as one can conscientiously and truthfully accomplish any of these steps, it constitutes valuable work.” This exposition fully reflects his emphasis on historical sources.

Whenever Guo began new research, he first sought to gather relevant sources as comprehensively as possible, insisting that investigation should begin with evidence rather than assumption. When he turned to the study of oracle bone and bronze inscriptions, he built close ties with Japanese scholars, exchanging materials and sharing resources. He also corresponded with leading domestic scholars such as Rong Geng and Dong Zuobin, asking them to help purchase materials and rubbings; his requests were almost always met with enthusiasm. He continued to track newly unearthed artifacts and related publications, continuously expanding his fields of inquiry, revising and refining his own arguments. Through this process he made tremendous contributions to the study of ancient Chinese scripts.

During the stalemate phase of the Chinese People’s War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression, Guo concentrated on the study of pre-Qin philosophy, for which he had made thorough preparations: “As for materials prior to the Qin and Han dynasties, I have more or less gone through them all in detail. In archaeology, philology, paleography, phonology, and Buddhist logico-epistemology, within the limits of what I could reach, I have done all the preparation and exploration possible.”

In the 1950s, Guo resolved to collate Guanzi [an ancient Chinese political and philosophical text named for and traditionally attributed to the 7th century BCE philosopher Guan Zhong]. To this end, he collected numerous editions and borrowed manuscripts from various places, eventually gathering 17 editions of Guanzi dating from the Song Dynasty onward, along with nearly 50 annotated editions and studies from both China and Japan since the 12th century. By sheer breadth of collection, Guo far surpassed his predecessors.

In 1957, during a discussion with researchers at the Institute of History of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, renowned historian Qiu Xigui asked Guo why, on the issue of periodizing ancient history, scholars working with essentially the same sources often arrived at different conclusions. Guo countered by asking: “Have you gathered all the sources there are?” This question spurred Qiu to consult historical materials with even greater diligence.

Guo attached great importance to excavated artifacts, regarding them as first-hand materials. When he began researching ancient Chinese society in 1928, he relied primarily on ancient classic texts like The Book of Songs, The Book of Documents, and The Book of Changes. Yet after completing “Social Transformations in the Age of the Book of Songs and Their Intellectual Reflections,” he began to doubt their reliability: These works, “though generally believed to be reliable, have been transmitted for thousands of years, filled with countless interpretations from previous generations. Their compilations inevitably contain errors and confusions, and the texts have undergone repeated copying. Most problematic is that none of the three books has a definite chronological standard. Thus, the vision of antiquity I constructed from them carried the risk of being little more than a mirage. I therefore deeply felt the necessity of studying archaeology and related fields. My research into oracle bone inscriptions and the bronze inscriptions of the Shang and Zhou dynasties began from this realization.”

He later remarked that excavated materials often held the key to resolving historical questions, underscoring his emphasis on archaeological evidence. Guo grew adept at “reversing verdicts,” mainly by using excavated artifacts to challenge transmitted texts. For example, he argued that the Zhouguan (Rites of Zhou) could not be a work of the Western Zhou period, since many concepts it mentioned were absent from bronze inscriptions of that period [as bronze inscriptions were popular mainly during the late Shang and Western Zhou dynasties]. Similarly, he contended that the transmitted Preface to the Orchid Pavilion Gathering [a work of Chinese calligraphy generally attributed to the well-known calligrapher Wang Xizhi] was in fact not written by Wang Xizhi, as excavated steles and manuscripts revealed no comparable running-script style from that era. Beginning with unearthed materials, Guo paid particular attention to the physical forms of writing and offered incisive discussions on issues such as the techniques of oracle bone inscriptions and the evolution of Chinese characters.

Distinguishing sources to clarify historical laws

Exerting every effort to collect materials can only establish a foundation for research—the next step is to determine their authenticity and chronology. Guo repeatedly stressed the importance of textual verification: “Once historical sources are in hand, one must distinguish the true from the false, examine their dates, discard the dross, and retain the essence. This process of scrutiny is what is called kaoju [textual criticism, a research method that examines documents and historical sources, compiling and analyzing evidence in order to verify facts and reach conclusions]. Such work is indispensable and must be affirmed.”

He put this principle into practice in major works distinguished by rigorous textual criticism, such as “The Dating of the Mao Gong Ding,” “A Critical Inquiry into the ‘Rites of Zhou,’” and “The Time of Compilation of the ‘Zhouyi.’” When collating the Ya Zhou Zhi [a local gazetteer from the Qing Dynasty], he personally inspected the shores of mountains, leapt across stone cliffs, searched along remote paths, and traced the weathered stone inscriptions from more than seven centuries earlier in order to verify and correct the original text. Though certain of his conclusions may be debatable, his scholarly approach was widely recognized within the academic community.

For Guo, seeking truth from facts could not be confined to textual criticism alone. Historian Fu Sinian once argued that modern historiography was merely the study of sources, but Guo disagreed. He maintained that textual criticism is only the preliminary stage of historical research. Without sources, history cannot be studied, but sources alone do not constitute historiography. In the past, he argued, traditional historians had stagnated at this preliminary stage and mistook it for the whole of scholarship—a serious error.

Textual criticism, then, was only a beginning. Scholarly research must extract patterns from abundant facts: “To truly seek truth from facts, history must be studied with a new historical outlook. Once the sources have been gathered and organized, how to use them becomes the more important issue in historical research. If one possesses sources but does not apply the methods of dialectical materialism and historical materialism to analyze and study them, it is like a cook who has fish, meat, vegetables, and tofu but has not prepared them—hardly a proper dish. The aim of historical research is to use abundant sources to concretely explain the laws of social development.”

Thus, in Guo’s view, “the ultimate purpose of ‘compilation’ lies in ‘seeking truth from facts.’ Our spirit of ‘criticism’ must aim to uncover the reasons behind facts. The method of ‘compilation’ can only achieve knowledge of ‘what is so’; our spirit of ‘criticism’ must attain knowledge of ‘why it is so.’ ‘Compilation’ is certainly a necessary step in the process of ‘criticism,’ but it cannot be the only step to which we confine ourselves.”

Updating academic views based on reality

In academic research, adhering to the principle of seeking truth from facts also means constantly revising one’s scholarly views in light of actual circumstances. Guo believed that “mistakes are inevitable, but what matters is not to conceal them, and to correct them with courage. Take myself as an example: Over the past twenty-odd years, my own views have changed several times, and it is almost as if the ‘me of today’ is constantly struggling with the ‘me of yesterday.’”

When writing Studies on Ancient Chinese Society, Guo misjudged the chronology of certain sources, following existing research and mistakenly treating the Shang Dynasty as belonging to the late stage of primitive society. He later revised this view multiple times. In the 1950s, he specifically stated: “More than twenty years ago I held a very mistaken opinion, namely that I regarded the Shang Dynasty as both the Chalcolithic Age and the final stage of primitive clan society. A few friends are still influenced by me even now, and I ought to confess my mistake openly. That view, from today’s perspective, is certainly wrong; but even at the time when I first held it, I already felt it was not entirely sound. In particular, when I was writing the section ‘Explanation of the Heavenly Stems and Earthly Branches,’ I realized that the level of astronomical knowledge at the time was fairly advanced—something hardly explicable within the framework of primitive clan society. Yet I stubbornly clung to my earlier interpretation and glossed it over. This deserves self-criticism: When doing scholarship, I did not sufficiently uphold the principle of seeking truth from facts.” “I sincerely repeat: The responsibility is truly mine. It was I who erred in identifying the Shang Dynasty with the Chalcolithic Age and the end of primitive clan society. I hope my friends will seek truth from facts and discard such an incorrect judgment in light of historical evidence.”

It was precisely because Guo consistently upheld “seeking truth from facts” that he was able to ground his scholarship in solid and abundant evidence, continually revise his views in light of new discoveries, and extract historical laws. In doing so, he opened new horizons in the study of ancient history and became a founding figure and leading authority in Chinese Marxist historiography.

Li Bin is a research fellow from the Research Management Division of Chinese Academy of History under Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

Copyright©2023 CSSN All Rights Reserved