Appropriate confrontation conducive to Chinese and Western cultures

Author : BAI LE Source : Chinese Social Sciences Today 2017-04-24

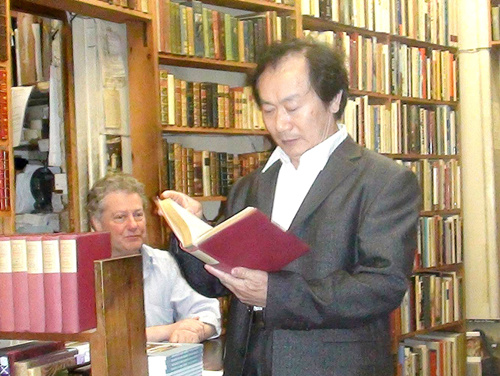

Born in 1951, Gu Zhengkun is the former director of the Institute of World Literature Study at Peking University. He is also the co-president of the International Association for Comparative Studies of China and the West, and the chairman of the Society for Shakespeare Study under the China Association of Foreign Literatures. He masters English and is able to read French, German, Ancient Greek, Latin, Japanese and Esperanto literature. He has published more than 50 books and is the editor-in-chief of RSC (Royal Shakespeare Company) Edition of Complete Works of Shakespeare (Chinese Version.)

He is not only a foremost expert on Shakespeare in China, but also a known scholar in the field of comparative culture. He wrote in 1988 that in the future, China would reform its hukou, or household registration, system to narrow the development gap between urban and rural areas, and currently, hukou reform is one of China’s priorities. On the eve of the Iraq War, he borrowed the words of Lao Zi to warn against the aftermath of the possible war: “Military actions usually invite great retaliation and famine.” Years later, an economic crisis broke out in America from which the country has not fully recovered.

Online, he has been hailed as sagacious, profound and far sighted. He has also been called astonishingly erudite and praised for his proficiency in Chinese and English as one of the nation’s best translators. A CSST reporter recently interviewed Professor Gu Zhengkun, who was also the first guest invited to lecture on the similarities and differences between Chinese and Western cultures on the CCTV program Lecture Room.

CSST: In your opinion, different disciplines are closely linked and related to each other, and this is why you stress comprehensive multi-disciplinary reading. As a scholar of humanities, you have a good knowledge of natural science. Therefore, you advocate generalist education. Please talk about the relationship between professional specialization and general knowledge in academic study.

Gu Zhengkun: I have had an ardent love for reading since childhood. Other than reading, thinking, discussion and writing, I have almost no other hobbies that was how I spent my past life years. I love reading books of any discipline, with great relish and gusto, and what I am mostly diligent on are books about Buddhism. I have read for more than 50 years and altogether more than 5,000 books have been read, bringing me great pleasure. What I learned from extensive reading is that being encyclopedic (resembling what is called the generalist education) is the basis and being professional is the enhancement. Scholarship and thinking is like the pyramid if the basis is solid, it can be firm even if it towers into the sky; if the basis is weak, forcing it upward creates the danger of collapse. Therefore, I have always recommended being a thorough master by making comparative studies: between the past and the present, between the humanities and sciences, between the Chinese and the foreign. Being professional could be better achieved only if it is based on being general.

This interview question involves the issue of the global education system. Today, most countries education systems do not encourage achieving a general mastery of knowledge that much, but instead encourage professional specialization. Experts and specialties are preferred because they solve concrete, practical problems. General studies (in encyclopedic sense) as a major is almost nonexistent globally. In fact, today’s doctoral graduates usually possess a narrow range of knowledge. They are only able to conduct research and write essays on particular topics under a particular discipline; a doctor produced in the context of the modern education system is different from, and even the polar opposite of someone who is erudite in the traditional sense.

In my opinion, an ideal educational system should ensure that 85 percent of the graduates are specialists and 15 percent are generalists; the former are people like Guan Yu, Zhang Fei, and Zhao Yun who were generals under warlords in the Three Kingdoms period in Chinese history, and the latter category includes people like Zhuge Liang, a politician of the same era. If there are only specialists but no generalists, the management mechanism of society must be defective. However, the disciplinary divisions across the world tend to be overly specific. I think China could absolutely reform its education system in the sphere of disciplinary integration and generalist education so as to overtake the global education.

CSST: You predicted as early as 1980s that there will be renewed interest and boom among Chinese academics in Sinology. Today, the boom is taking place as you said. On what grounds did you make this prediction? Meanwhile, some scholars argue that the renewed interest is overheated and we need “cold, detached thinking” about it. Do you agree?

Gu Zhengkun: I made many predictions and most of them have come true. I predicted during the period of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution that China would definitely take the path of a market economy years later. With regard to my basis for making the prediction, it is really complicated to say—each prediction is underpinned by a number of parameters.

I agree with the argument that the renewed interest in Sinology is necessary but should not be excessively heated up, which would otherwise be unwholesome. What is Sinology? The Modern Chinese Dictionary says that Sinology means the traditional Chinese classics, scholarship and culture, including philosophy, history, archaeology, literature and linguistics—this has been the conventional definition of Sinology since the late Qing Dynasty (1636-1912) and early Republic of China (1912-1949) period. However, it is flawed. Although it is an impartial list, implying that Sinology includes more than aforementioned five disciplines, actually the definition emphasizes these five.

In recent years, I have been lecturing on Sinology and I propose to redefine it, which, as I perceive, is the renewed integration of the traditional, modern and contemporary Chinese classics, scholarship and culture—in other words, the sum total of the unique Chinese scholarly and cultural achievement spanning from the ancient times to today. From my point of view, the range of Sinology can be expanded broadly to include the I Ching study, geography, linguistics and philology, religion, philosophy, ethics, politics, economics, law, ritual study, literature, art, education, sports science, traditional Chinese medical science, musicology, astronomy, agronomy and engineering technology science. Sinology should cover at least 20 disciplines, with each discipline subdivided into many categories. For example, religion includes Taoism and Buddhism while politics includes Legalist, Confucianist, Mohist, Taoist and other schools of thought. In addition, Sinology needs to connote uniquely Chinese civilization that is distinctive from modern Western scholarship and culture.

According to the aforementioned definition, there are three major defects of the current renewed interest and trends in Sinology: Many mistakenly perceive it as partially the study of Confucianism, which, in fact, is an important branch of Sinology but should not be overstated. In addition to Confucianism, there are 20 other disciplines that need to be advocated for Sinology. Sinology should also include Marxism, Mao Zedong Thought as well as modern and contemporary Chinese cultural achievement.

In addition, Sinology is not limited to the traditional Chinese moral values and notions. Take Confucianism for an example. The essential moral and ethical notions of Confucianism are no more advanced than those upheld by the Communism of the New Age. Confucianism, fundamentally and ultimately, preaches the feudal hierarchical concept. Estranged from the egalitarian, self-reliant, independent and open concept encouraged by the modern world, Confucianism should not be completely accepted. Filial piety might be one major merit of Confucian concepts, which should be insisted upon, but in fact, it is not peculiar to Confucianism. Most creeds emphasize devotion to parents, respect for the elderly and care for the young—just to different extents.

CSST: You lectured on Western philosophy in Peking University. You said that some of the most surprising thoughts and theories of Western philosophy emerged in Chinese philosophy far earlier, a fact that we unfortunately neglect.

Gu Zhengkun: I said so. Take one example. Heraclitus, the great Ancient Greek philosopher, characterized all existing entities by pairs of contrary properties, and he even insisted that the deity is equal to the union of opposites. This was a remarkably and astonishingly important idea in the West. However, in traditional China, the ancient Yin-Yang schools and I Ching experts who lived in a far earlier period, had already had such ideas. They believed all existing entities of the universe are constituted by Yin and Yang, the two complementary but opposite, contrary forces that interact to form a dynamic system. As is stated in the Chinese classic I Ching, Yin and Yang are components of a Oneness that is also equated with the Tao. Furthermore, Lao Zi interpreted the opposition theory of Yin and Yang by connecting it to the Tao. From Lao Zi’s perspective, Tao means non-being and Yin-Yang means being. Yin and Yang emerge from the Tao, that is to say, steming from non-being; being and non-being produce each other. It can be seen that the dialectic relations between being and non-being as a unity of opposite expounded by Lao Zi were more ingenious and masterly than Heraclitus’s theory of unity of opposites. And Lao Zi, about 30 years older than Heraclitus, put forth these ideas much earlier.

CSST: Francis Fukuyama in his book The End of History and the Last Man asserted that the United States would embrace its heyday after the collapse of the Soviet Union. You wrote at the same time that the history did not end but just began. The disintegration of the Soviet Union was hardly a good sign for the United States which would decline from then on. But a centipede does not topple over even after it has been dead and the United States will linger on for quite a long time span instead of falling apart soon.

Gu Zhengkun: I talked about this issue in the International Conference of Cultural Dialogue and Misreading in 1995 and the original English speech was later published by the University of Sydney Press. I said that the development of culture itself always comes to a standstill wherever cultural contradictions are completely eliminated. Just to give one simple example. With the disintegration of the Eastern European socialist camps, especially the Soviet Union, the ideological confrontation between the two countries—America and Soviet Union—ended. Americans have reason to see this as their victory.

But from a long-term point of view, the Americans may not have really gained great advantages by unfair means. They should understand that for decades, there had been a strong confrontation between the Soviet Union and the United States in terms of cultural ideology, such as the violent criticism of the capitalist ideology on the part of the socialist ideology, which has undoubtedly promoted the US ruling groups to make corresponding improvements in their political, economic and cultural institutions to varied degrees.

In other words, the competition between the Soviet Union and US has played a positive stimulating effect on the development of the two countries. Without the confrontation and threat from the Eastern European socialist camp led by the Soviet Union, it would have been difficult for the Western capitalist camp to achieve the so-called prosperity that they have achieved today. This is just a verification of a Western proverb that “Wind kite rises against a little opposition.” Now, the socialist camp in Eastern Europe is occupied by the Western capitalist political and economic systems, the old rivals of the United States seem to have turned into friends. But I can firmly assert that the aforementioned situation is hardly a good sign for the US. The absence of confrontation is bound to hinder the winner. Or in terms of Toynbee, no challenge, no response. Moreover, Eastern Europe is waiting for American charity. It is no longer an opponent for America in cultural ideology, but it will become an economic burden of the Americans and potential economic competitors. The United States was a winner in the gamble, but when it comes to the final financial settlement, it will probably find itself actually to have lost capital. The same logic can be used to explain today’s Eastern-Western cultural confrontations. Western scholars of insight may see that preserving China as the world’s largest socialist experimental field and as an opponent to the Western capitalist camp, is undoubtedly conducive to the development of the West.

I wrote in another article that the whole world should advocate the protection of traditional Chinese culture from the perspective of cultural ecology. The world’s cultural scholars, especially Western cultural scholars, should be aware of the importance of protecting the traditional Chinese culture. All the cultural scholars of the globe should be aware of the importance of protecting primitive communism and traditional socialist beliefs. With the collapse of the Soviet socialist camp, history has not ended as Fukuyama happily announced but rather has just started. I can boldly predict that an attempt at truly mature communism or socialism will flourish in the near future. And the United States will most likely be the next country where the new socialist experiment begins.

Perhaps my prediction that the United States will be where the new socialist experiment begins is the boldest prediction I have ever made. I really hope that those who have read this interview-article would have the opportunity to witness the advent of this day in their lifetime.

Ye Shengtao made Chinese fairy tales from a wilderness

Ye Shengtao (1894–1988) created the first collection of fairy tales in the history of Chinese children’s literature...

-

How northern ethnicities integrated into Chinese nation

2023-09-18

-

Mogao caves

2023-09-12

-

Mogao Grottoes as ‘a place of pilgrimage’

2023-09-12

-

Time-honored architectural traditions in China

2023-08-29

-

Disentangling the civilizational evolution of China

2023-08-28

-

AI ethics in science fiction

2023-08-23

2011-2013 by www.cssn.cn. All Rights Reserved

2011-2013 by www.cssn.cn. All Rights Reserved