Dai Yi speaks on Qing history national compilation project

Author : GUO FEI Source : Chinese Social Sciences Today 2020-04-25

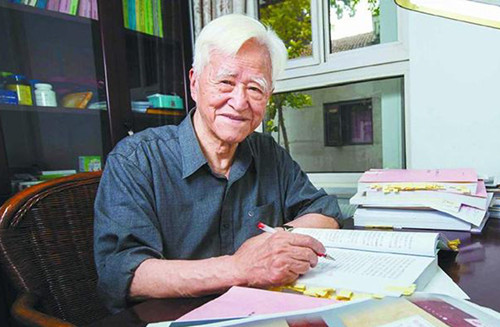

Dai Yi is one of the pioneering scholars who have elevated the history of the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911) into a discipline. In 2002, the National Project for the Compilation of Qing History was started. Director of the National Qing History Compilation Committee, Dai has committed painstaking efforts to the development of this project, whose achievements are in the midst of a review process. In an interview with Chinese Social Sciences Today (CSST), Dai speaks on the compilation project and the role of big data in historical research.

CSST: As a master scholar in the study of Qing history, can you talk about your understanding of the field?

Dai Yi: The history of the Qing Dynasty is an emerging research field. It has only been a little more than a century since the dynasty’s collapse, and China has undergone tremendous changes. After the Qing’s downfall, society in general held a low opinion about the dynasty, assuming that its reign was good for nothing and exemplified by political corruption, numerous cases of literary inquisitions and the massacre of ordinary people. Judgments of this kind show no objectivity. Before 1949, there were few scholars studying Qing history beyond the first generation of Qing history scholars, such as Meng Sen and Xiao Yishan, thus the field failed to grow into a systematic discipline.

Circumstances got a lot better after the founding of the People’s Republic of China. The first sign of improvement was an emphasis on the study of Chinese history after the Opium War (1840–1842). Historical studies of modern China came to fruition due to the establishment of the Institute of Modern History under the Chinese Academy of Sciences in 1950 and the recruitment of professionals. The institute now is affiliated to the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (which was established in 1977). Most of these studies, however, have a singular focus on the period after 1840, pushing the peak of the research toward late Qing history. Comparatively speaking, there was a long time in which few Qing history experts looked at the period before the Opium War. It was not until 1978 that the academic community began to attach importance to studying the entire Qing history.

At that time, there was an evident shift in academic circles’ attitude toward the Qing Dynasty. We know that the Qing court, during its late period, lost almost all wars with foreign countries, but it also had some contributions. For example, the territory of the Qing Dynasty basically laid out the territory of China today. Such a large territory has been rarely seen in world history. I think the Qing’s vast territory has provided the country with the foundation and premise for its development, at least. This was the Qing Dynasty’s most precious wealth passed down to its descendants. Therefore, the Qing Dynasty was not completely corrupt; it also left many valuable legacies.

The Qing Dynasty had five wars with foreign countries in its late period, which were the First Opium War (1840–42), the Second Opium War (1856–60), the Sino-French War (1883–85), the Sino-Japanese War (1894–95) and the invasion of the Eight-Power Allied Forces in 1900. The Qing court failed to win any of them. It was defeated but the nation was not discouraged. In fact, the Chinese People’s War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression (1937–45) was a victory. Moreover, the entire Chinese nation participated in the war with all ethnic groups united, repelling the aggression. This was a huge change.

Without a thorough study, we might think the reign of the Qing Dynasty was unbearable. After careful analysis and study, however, we will find that the entire Qing Dynasty does have qualities worth inheriting and learning from. This thinking pattern, if adopted to expand research, may lead us to a more comprehensive and objective understanding of the Qing Dynasty.

CSST: You have been devoted to the National Project for the Compilation of Qing History. Please briefly talk about the compilation work in terms of content and features.

Dai Yi: The Qing Dynasty lasted for about 300 years, and that is not a short time. It also marked the transition where ancient society began to move towards modern society. The dynasty was the outset of the modernization of Chinese society. In the late Qing, society started to change in multiple ways as many new things mushroomed. Social life became much more diverse. Therefore, being all-encompassing, the compilation of Qing history highlights the role of the people in its content. Also, the project is innovative in its style.

During the compilation of the chronicle of Qing history, we classified the new content we discovered. For example, we added the newspaper category by designing a statistical table of Qing Dynasty newspapers. What newspapers were there at the time? When and where did they appear? How long did they exist? Who operated them? Regarding these issues, we have done our best to collect and sort out the pertinent information. We also made tables for treaties and regulations signed with foreign countries. In the late Qing Dynasty, railways emerged in China. The steamship sector also evolved, and there were many banks. Familiar names like Beijing-Zhangjiakou Railway, China Merchants’ Steam Navigation Company, the Imperial Bank of China and the Bank of Communications were all established during this period. Therefore, we compiled histories of railways, steamships and banks respectively. Even a stock market took shape at the time, like the rubber stocks. These terms can be discovered in historical materials though they were poorly documented.

It deserves mentioning that since the Opium War, the importance of customs work and regulations elevated continuously due to the gradual development of trade. Right up to the outbreak of the Revolution of 1911, the Qing court’s annual customs revenue exceeded the total of its other revenues. There is a section introducing the financial situation of the Qing Dynasty, and we added a history of customs, because the customs situation in the late Qing period was too vital to ignore. Furthermore, the project includes compiled records of borders and territorial seas.

We have absorbed many new things in the process of compiling Qing history. One of the major features is our highlighting of the people. As for the cultural part, in addition to poetry and prose, items such as novels, dramas, Peking opera, acrobatics, embroidery and clay figurines were noted, while categorizing various forms of skills and juggling. New biographies of famous craftsmen were added. In history books, we want to reflect the real lives of ordinary people in a broader scope.

After finding information on the craftsmen who could make the best rice paper, ink, inkstones and writing brushes, we will write biographies and books for them. As for Go and Chinese chess, we found documents about some national players at the time and included them in the compilation. We also covered many martial arts players. Martial arts used to be considered unrefined by the old society, but we think they were created by the working people. After the Opium War, photography became available in China, and many people thus took photos. We selected 8,000 photos from more than 200,000. In this way, the compilation of Qing history is like an encyclopedia. We hope to present a comprehensive and profound work brimming with concrete details.

CSST: Since you published the article “Retrospect and Prospect of Historical Study in China at Turn of Century” in 1999, more than two decades have passed. What research fields should the focus of Chinese historiography today?

Dai Yi: I have invested all my energy into the Qing history compilation project. My thoughts on historical study in general have dwindled. Regarding the study of history, we should pay attention to the impact of big data and artificial intelligence, but only time will tell how much the impact will be. Currently, big data already plays a large role, as it can help collect abundant materials. As we all know, the study of history requires reams of archival materials. The advantage of using a computer to search for information is convenience and speed. Time is precious.

When writing Emperor Qianlong and His Time, I read the entire section on the emperor in the Veritable Records of the Qing Dynasty in addition to his collection of poetry and prose. To date, the emperor is credited with writing more than 40,000 poems over his life, and I read them all. There were immense collections of books written during the Qing Dynasty. Over the past two decades, artificial intelligence and computer technology have made huge strides, and now big data search technology has been widely applied to historical study. In the past, it was very tedious to collect newspapers. Without the aid of big data, it is almost impossible for one to gather information comprehensively.

In recent years, the field of historical research has continuously expanded. Since the reform and opening up, Chinese academic circles have increasingly interacted with their international counterparts. There have been some new achievements as Chinese scholars consciously examine Chinese history in a global context for comparative studies. Although there are many books in the field of history, most of them are concerned with relatively micro and fragmented issues, displaying the feature of fragmentation and a lack of grand influence. But I believe that sooner or later our academic endeavors will produce more influential works.

(Edited and translated by MA YUHONG)

Ye Shengtao made Chinese fairy tales from a wilderness

Ye Shengtao (1894–1988) created the first collection of fairy tales in the history of Chinese children’s literature...

-

How northern ethnicities integrated into Chinese nation

2023-09-18

-

Mogao caves

2023-09-12

-

Mogao Grottoes as ‘a place of pilgrimage’

2023-09-12

-

Time-honored architectural traditions in China

2023-08-29

-

Disentangling the civilizational evolution of China

2023-08-28

-

AI ethics in science fiction

2023-08-23

2011-2013 by www.cssn.cn. All Rights Reserved

2011-2013 by www.cssn.cn. All Rights Reserved