Three Theories of Inflation In China

Author : Source : Chinese Social Sciences Net 2012-07-11

In May 2012, the year-on-year growth rate of China’s consumer price index (CPI) dropped to 3.0%, the low point since June 2010. In the same month the year-on-year growth rate of China’s producer price index (PPI) also fell to 1.4%, the third consecutive month of negative growth since March 2012. The decline of inflationary pressure has enlarged the space for the central bank to ease the currency policy. The central bank recently cut the legal deposit-reserve ratio once, and then cut the benchmark interest rates again. If China’s macroeconomic and asset price trends depended largely on monetary policy in the future, and the latter depended on the inflationary pressure, then it would be of vital significance to analyze the trends of China’s inflation. How should we judge China’s inflation trends? If we understood the following three theories on China’s inflation, we might be able to have a relatively complete analytical framework for China’s inflation trends.

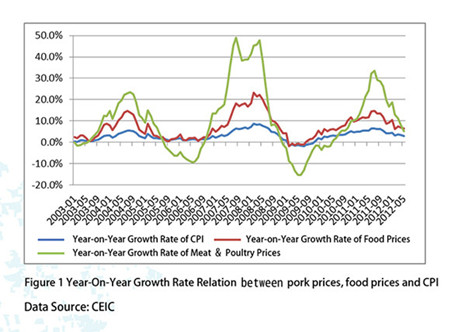

The first theory of China’s inflation is "food prices (pork prices) determinism." The core idea of the theory is that the trends of China’s CPI are largely decided by the trends of food prices, and the trends of food prices depend on the changes of pork prices. As shown in figure 1, first of all, in the past 10 years, there were significant positive correlations on year-on-year growth between the CPI, food prices and meat & poultry prices. Secondly, the fluctuation range of meat & poultry prices is significantly larger than that of food prices, and the fluctuation range of food prices is far larger than that of the CPI. Thirdly, in most cases, the change of the meat & poultry prices were ahead of that of the food prices, and the changes of the food prices in turn ran ahead of the CPI changes. Finally, the changes of the year-on-year CPI growth rate, food prices and meat & poultry prices were cyclical, and a full cycle lasted roughly three years.

How to understand "food prices determinism"? In China’s CPI basket, food accounts for 30%, and meat & poultry account for one third within the food category. Generally speaking, the fluctuation range of meat & poultry prices is larger than that of other kinds of food, and relative to other commodities, the fluctuation range of food price is larger. Therefore, the fluctuation of pork price leads to the fluctuation of food prices, and it is not difficult to understand that the fluctuation of food prices leads to the whole CPI fluctuation. In addition, the fluctuation cycle of the CPI, food prices and meat & poultry prices is generally called "the pig cycle", and the frequency of this cycle is related to the farmers’ pig-raising behavior. When pork prices start to rise, farmers begin to increase the rearing of piglets, and the cycle from rearing to selling is usually of one year and a half or so. This means that it takes around a year and a half for the market supply of pork to go from a shortage of supply to supply-demand balance. It is not difficult to see that the economic logic of “the pig cycle” is similar to the famous "spider web model."

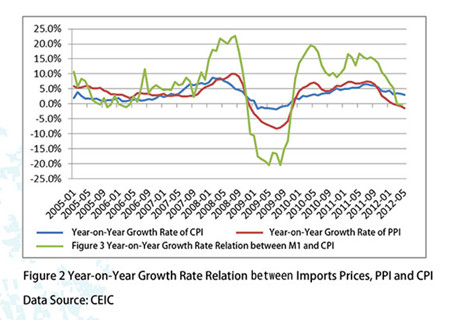

The second theory of China’s inflation is "imports prices determinism." Its core message is that, the fluctuation of import prices determines PPI fluctuation, and PPI fluctuation determines CPI fluctuation. As shown in figure 2, since 2007, there have been significant positive correlations for year-on-year growth between import prices, PPI and CPI. Secondly, the fluctuation range of import prices was notably larger than the PPI fluctuation range, and the PPI fluctuation range was larger on average than the CPI fluctuation range. Thirdly, in most cases, the change of the import prices was ahead of the PPI, and the change of the PPI was ahead of the CPI. Finally, there was no definite rule for these three periodic fluctuations.

How to understand "imports prices determinism"? At present, China’s manufacturing industry depends mainly on imported energy and bulk commodities. If the prices of international energy and commodities went up, it would first lead to an increase of production costs in most Chinese importing enterprises, and then cause the PPI to go up. The manufactured goods with a raised price then enter in the market circulation, which causes the CPI to go up. With the increasing dependence of China’s manufacturing on imported raw materials and intermediate products, “import price determinism” will become more and more important.

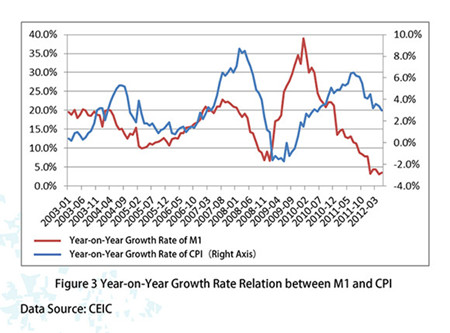

The third theory of China’s inflation is "monetary amount determinism." The core idea is that China’s inflation is determined by the amount of currency issued by the central bank. As Friedman said, inflation is a monetary phenomenon at anytime and anywhere. As shown in figure 3, in the past 10 years, there has been a significant positive correlation between the monetary base (M1) and the year-on-year growth rate of the CPI. The change in the year-on-year growth rate of the M1 is ahead of that of the CPI, but the length of time from the M1 inflection point to the CPI inflection point is not consistent, about a year and a half.

From the three stories, we can have a systematic framework for analysis of the inflation trends in China. As shown in figure 1, at present, the year-on-year growth rates of meat & poultry prices and food prices is falling. As shown in figure 2, the year-on-year growth rate of the imported prices index and the PPI is also declining. As shown in figure 3, the year-on-year growth rate of the M1 has not yet got out of its downturn so far, being still at historic low. The three theories predict that in the second half of 2012, the year-on-year growth rate of China’s CPI will remain low. The year-on-year growth rate of the CPI in 2012 might be around 3% and this will broaden the space for the central bank to ease monetary policy. Once the monetary policy becomes clear, there would be a soft landing of China’s economy and we can be optimistic about the prospect of China’s asset prices in the second half of 2012.

The last interesting question is whether China’s inflation is endogenous or exogenous. If you agree with “food prices determinism” and “monetary amount determinism,” it seems China’s inflation is mainly endogenous, and domestic macroeconomic trends and monetary policy determine the fluctuation of China’s inflation. If you agree with “import price determinism”, it seems China’s inflation is mainly exogenous, and the trends of international energy and commodity prices determine the fluctuation of China’s inflation. We can make a further analysis, to a certain extent, by pointing out that Chinese pork price is related to the corn price (corn is one of the main feeds for pigs), and corn price is related to energy price (that crude oil price goes up would propel the development of biofuels, and corn is the main raw material for biofuel ethanol). This means that the fluctuation of China’s food prices is partly affected by the fluctuations of global energy and commodity prices.

How to combine the above two ideas in our analysis? In fact, as far as we know, in the past 10 years, the import demand from China to a large extent influenced the trends of international energy and bulk commodity prices, and the so-called "imported inflation" in fact may also be endogenous. Of course, the conclusion needs to be tested by more strict empirical analysis, and it is not within the scope of this article.

The author is a research associate of the Research Center for International Finance, CASS.

Translated by Chen Meina

Ye Shengtao made Chinese fairy tales from a wilderness

Ye Shengtao (1894–1988) created the first collection of fairy tales in the history of Chinese children’s literature...

-

How northern ethnicities integrated into Chinese nation

2023-09-18

-

Mogao caves

2023-09-12

-

Mogao Grottoes as ‘a place of pilgrimage’

2023-09-12

-

Time-honored architectural traditions in China

2023-08-29

-

Disentangling the civilizational evolution of China

2023-08-28

-

AI ethics in science fiction

2023-08-23

2011-2013 by www.cssn.cn. All Rights Reserved

2011-2013 by www.cssn.cn. All Rights Reserved