Yuan’s postal system facilitated East-West trade, cultural exchange

Author : WUYUN GAOWA Source : Chinese Social Sciences Today 2017-04-13

At its peak, the Yuan Dynasty stretched as far north as Mongolia and Siberia while traversing the South China Sea. To the west, it included Tibet and Yunnan while it encompassed eastern Xinjiang in the northwest and bordered the Okhotsk Sea in the northeast. The perfected postal network helped maintain imperial rule over the vast territory.

The Yuan Empire (1206-1368) was the first national regime established by a northern nomadic tribe. After Genghis Khan conquered the Mongolian tribes and founded the Mongol Empire, his grandson Kublai Khan unified the territory of China into a nation of multiple ethnic groups and cultures.

What remained consistent was the regime’s commitment to building post stations and a postal system. It not only created an effective transportation network for people-to-people exchanges, foreign and domestic tribute, trade and cultural communication between the Central Plains and neighboring states, Central, West and East Asia as well as Eastern Europe but also was instrumental to its rule over subjugated populations throughout the empire, thus promoting ethnic integration and cross-cultural dialogues.

A post is called zhanchi, which is the Chinese transliteration of the Mongolian jamci, in which jam means “road and transportation.” The Mongolian jamci was also understood by Western travelers to mean a “manager of postal relay stations,” and it bore the connotation of a guide. The origins of the Mongol jamci system, however, remain obscure.

Vast, broad network

In antiquity, the Chinese had their own postal relay systems that rivaled those of the Persians and the Romans in transmission and delivery of official documents and military intelligence. The Yuan rulers inherited an old and established tradition of postal relay systems. They endeavored to expand the network to cover the extent of their territories and enforce effective regulations.

The Mongol postal service was under the supervision of the Bureau of Transmission (Tongzheng yuan), an agency of the central government. Most officials in the bureau were Mongols and semu people, or Western and Central Asians, even Europeans, because of their proficiency in the Mongolian language. The decree was also written in Mongolian.

Genghis Khan first ordered the building of postal stations, and Ogodei Khan later linked the various networks that were under the control of his brothers in other khanates into one system, contributing positively to East-West communication.

Once the system was established, households were assigned to various posts called zhanhu, or “post station household,” and they were responsible for meeting the needs of relay horses, staff and official travelers by providing food, shelter and whatever else necessary.

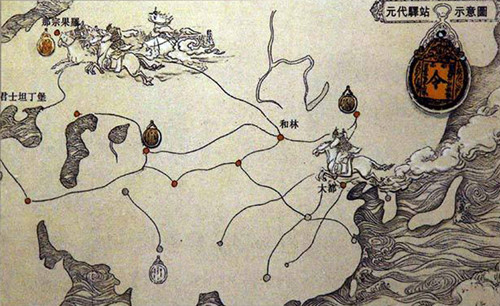

Under the reign of Kublai Khan, the Yuan Dynasty established a network of post stations radiating from the imperial center that served the messengers in the Great Khan’s efficient postal system. China had more than 1,500 postal stations on land and sea across the breadth and length of the empire at the time.

There was a post station every 60 li, a Chinese unit of distance that has varied over time. Traveling envoys and royal families carried an identification pass, known as paizi in Chinese, made out of wood, silver, gold, or bronze, and other official documents that granted them special privileges to use the facilities and obtain food.

In addition to providing facilities for lodging and postal services, the Yuan rulers also set up an express delivery system, in which couriers were soldiers who traveled on horseback or on foot to pass on documents and intelligence. The couriers boasted a speed of 400-500 li in a day, or in some accounts, even up to 700 to 800 li.

Prosperous imperial center

Kublai Khan thought highly of Confucianism and adopted the Han nationality’s ruling philosophy. Upon taking the throne, he invited envoys, members of the royal family as well as other foreign and domestic guests to pay tribute in the capital city.

In 1276, a special accommodation quarter, Hostel for Foreign Envoys, or huitong guan in Chinese, was set up by the Yuan government to house foreign envoys and merchants visiting the imperial center.

It was indeed not only the Khan’s residence for visiting guests, but also became an institution that facilitated the flow of trade. Those merchants who bought and sold goods in huitong guan would be encouraged and rewarded by the emperors. Moreover, it was a center of language studies because many interpreters worked there to facilitate the exchange of trade and diplomacy.

In the end, merchants and others came in great numbers on business, pleasure, and political matters, making the capital a prosperous center for trade, culture and intelligence.

Multiple functions

The Yuan emperors were in essence from nomadic tribes in the north. Though they placed great emphasis on Confucianism and Han philosophy and inherited customs from the Tang and Song dynasties, Mongol management of the postal system was quite distinctive.

However, as broad and vast as the Yuan empire was, it could not adopt a unified model for governing the postal system, which is why its rules, horses and couriers varied on a regional basis in line with the differentiated geographical features in the Central Plains, northeastern forests and southern China.

It is worth noting that post stations and hotels in the Yuan Dynasty offered food with strong nomadic characteristics, especially those located in the north. For example, lamb was a major source of sustenance for foreign ambassadors and merchants. If lamb was not available, the substitute would be chicken.

In terms of functions, the Mongol posts and hotels served a variety of functions. Primarily, it facilitated communication throughout the vast empire, and played a key role in defense of borders.

In addition, the postal system shouldered multiple tasks, such as bureaucratic administration, escort for visiting envoys, transportation of materials, locations for trade, cultural services and the gathering of intelligence.

At every post, visiting guest could not only get food, horses and shelter, they could also acquire the guidance of postal servants. As a result, commerce began to thrive in the Yuan Empire and the capital became the center of trade where various sources of goods converged.

In the meantime, religious personnel, such as missionaries and monks also made full use of the postal system so that Taoism, Buddhism, Islam, Christianity and Hinduism could all thrive in the imperial state.

Land, sea trade routes

In the Liao and Jin dynasties, the Western Xia regime (1038-1227) occupied the area around the Hexi Corridor, a stretch of the Silk Road, the most important trade route between North China and Central Asia, and the trade route was suddenly interrupted. Merchants were forced to use the northern grassland silk route to continue trade between the Central Plains and the West.

After Genghis Khan created a unified empire from the nomadic tribes of northeast Asia and his descendants extended the Mongolian Empire across most of Eurasia, the central and local post stations built by the Yuan government revived both the Silk Road and the Maritime Silk Road and saw them reach their zenith.

Thanks to the postal network, Persian and Arabic culture was transmitted to the Central Plains and northern China. In cuisine, the Western Regions, Mongol and Han interacted. For example, the oat noodles in the Western Regions were quite popular among Mongols.

The Yuan government adopted a religious tolerance policy, and all sorts of religions were welcomed and allowed to develop freely. Phagpa was the fifth leader of the Sakya school of Tibetan Buddhism. Kublai Khan granted him regencies over the thirteen myriarchies of Tibet. He was granted the title Chogyal, or “Dharma King.” Tibetan monks used the post stations to commute between the capital and Tibet, contributing significantly to the development of Tibetan Buddhism in the Central Plains.

In the meantime, the Maritime Silk Road was also active. With posts along rivers and coastlines, goods from the capital were transported to harbors, such as Quanzhou, Guangzhou and Ningbo via the Great Cannon, then sent to East and Central Asia, to faraway Europe.

Fragrant goods from India and Southeast Asia, cloth from the West and other commodities were also transported to the Yuan Empire via the South and West China Sea, then to various domestic markets, largely promoting the development of trade, making the Yuan Empire far more prosperous than the Han and Tang dynasties.

Wuyun Gaowa is from the Institute of History at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

Ye Shengtao made Chinese fairy tales from a wilderness

Ye Shengtao (1894–1988) created the first collection of fairy tales in the history of Chinese children’s literature...

-

How northern ethnicities integrated into Chinese nation

2023-09-18

-

Mogao caves

2023-09-12

-

Mogao Grottoes as ‘a place of pilgrimage’

2023-09-12

-

Time-honored architectural traditions in China

2023-08-29

-

Disentangling the civilizational evolution of China

2023-08-28

-

AI ethics in science fiction

2023-08-23

2011-2013 by www.cssn.cn. All Rights Reserved

2011-2013 by www.cssn.cn. All Rights Reserved