The convents and priestesses of the Tigris and Euphrates river basins in ancient Babylon

Author : Source : Chinese Social Sciences Today 2013-12-25

When the word “convent” is mentioned, images of the convents and nuns of medieval Europe spring to mind. In fact a similar kind of convent had already appeared in the Tigris and Euphrates river basins as early as 2000 BC, at the time of Ancient Babylon. In these convents there dwelt a number of priestesses, who came to constitute a particular social class. They enjoyed the same social status as men and could engage in all kinds of political, economic and religious activities, and they made their own contribution to the prosperity and development of the culture of Babylon.

The priestesses who dwelt in the convents would engage in religious and economic activities

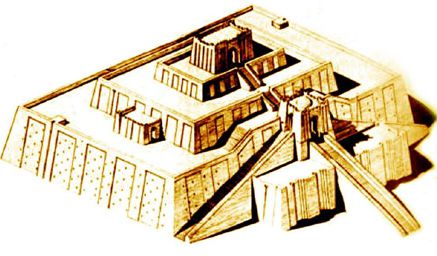

At the time, a convent would constitute an important part of a temple. It would be surrounded by high walls, and maintenance would periodically be carried out under the authority of the king of Babylon. The entrance of the convent was the place where priestesses would conduct economic transactions with the outside, and it would be guarded by people specially assigned. There were numerous houses available for the priestesses, the officials and the female weavers employed by the convent. The most important building would be the one used for recording the management of the convent and its granaries. The area occupied by a convent was usually quite large, but only a small part of it would be taken up by fields of castor-oil plants.

Although the convents had a large degree of autonomy, they were still subjected to the supervision of the Temple of Shamash. The staff of the convents was usually divided into two sections, one which managed public affairs, and another which managed and looked after the personal affairs of the priestesses. The American Assyriologist Harris estimated that there would be 200 to 500 priestesses and officials dwelling in a convent. The priestesses always owned their own houses, housekeepers, clerks and slaves. They therefore enjoyed easy lives and could conduct various economic activities with the outside. The convents were thus not only places of worship but also economic entities.

The classification and status of the priestess

Priestesses in ancient Babylon could be divided into two groups: those who lived inside the convents and those who did not. Some priestesses were not allowed to give birth to children, including the Nadītu of Shamash. This particular priestess enjoyed an extremely high status within society in general, as well as in economic and religious affairs. She could adopt a child as her successor, and the child would usually be her niece or a slave.

Surprisingly, a few of the priestesses could get married with ordinary men and remain with them, including the Nadītu of Marduk. She was however not allowed to give birth to children. In order to leave offspring for her husband, she would normally adopt a child or let other women give birth to a baby for her. These women had to obey the priestess, otherwise they would receive a harsh punishment or be sold into slavery.

The emergence of convents and priestesses was boosted by economic factors

In ancient Babylon, there were numerous factors which lead to the emergence of convents and priestesses, including various economic factors. At the time only a little of the society’s wealth was concentrated in the hands of the royal court and the temples, while the rest was in the hands of private individuals. In order to prevent a loss of wealth, most upper-class families chose to send their daughters to convents. This was because if their daughters got married they would take a part of the family assets away with them, and it could never be recovered. If they became priestesses they would also be provided with a dowry, but their family could recover that part of their assets after their death. In addition, these priestesses created wealth which would belong to their families. The social and economic circumstances of ancient Babylon thus encouraged the emergence of convents and priestesses. As ancient Babylon perished, its convents and priestesses gradually made their exit from the stage of history.

The author is from the School of History and Culture of Southwest University.

The Chinese version appeared in Chinese Social Sciences Today, No. 538, 18th December, 2013.

Chinese link: http://www.csstoday.net/xueshuzixun/guoneixinwen/86713.html

Translated by Chen Meina

Revised by Gabriele Corsetti

Ye Shengtao made Chinese fairy tales from a wilderness

Ye Shengtao (1894–1988) created the first collection of fairy tales in the history of Chinese children’s literature...

-

How northern ethnicities integrated into Chinese nation

2023-09-18

-

Mogao caves

2023-09-12

-

Mogao Grottoes as ‘a place of pilgrimage’

2023-09-12

-

Time-honored architectural traditions in China

2023-08-29

-

Disentangling the civilizational evolution of China

2023-08-28

-

AI ethics in science fiction

2023-08-23

2011-2013 by www.cssn.cn. All Rights Reserved

2011-2013 by www.cssn.cn. All Rights Reserved