Is Yu the Great a historical figure?

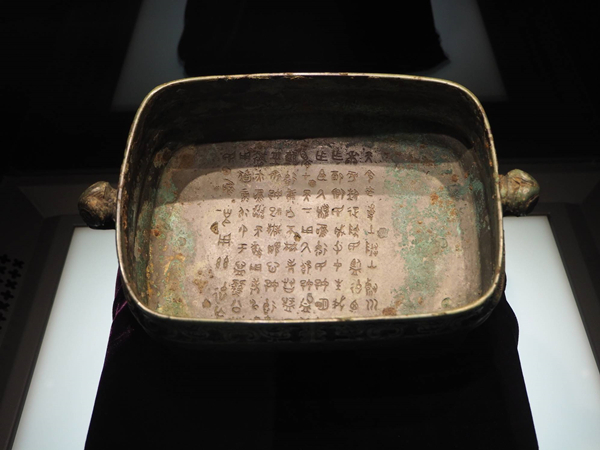

FILE PHOTO: The inscription on the Xu vessel of Duke Sui is currently the earliest recorded mention of Yu found in unearthed texts.

In Confucian teachings, Yu, or Yu the Great, generally known as the Tamer of the Flood and reputed founder of China’s Xia Dynasty, is venerated as the foremost of the “Three Kings” [the founders of Xia, Shang, and Zhou dynasties]. While various schools of thought have selectively augmented or adapted the accounts of Yu’s deeds, his major accomplishments have remained consistent across traditions. However, in the 1920s and 1930s, the Doubting Antiquity School, led by Gu Jiegang, launched a controversial debate centered on Yu, arguing that Yu was a mythological rather than historical figure. This revolutionary perspective sparked significant societal reactions, and its influence persists to this day. In recent years, the discovery of newly unearthed texts and archaeological artifacts has opened up fresh avenues for investigating Yu.

Yu in unearthed texts

In 2002, the Poly Art Museum in Beijing acquired a bronze object known as the Xu vessel of Duke Sui, dating to the early Western Zhou period. The inscription on the vessel is currently the earliest recorded mention of Yu found in unearthed texts. It recounts Yu’s divine mandate to map the land, delineate the Nine Regions [a pre-Qin concept referring to the entirety of China], manage waterways, and organize tribute systems—a testament to his monumental achievements. Similarly, the recently discovered Tsinghua Bamboo Manuscripts document the dialogues between King Wu of Zhou and his official, Hou Fu. In the beginning of the manuscripts, King Wu states: “I have heard of Yu... who was blessed by Heaven with people to establish the Xia Dynasty after he succeeded in controlling the floods.” This reflects the Zhou people’s acknowledgment of Yu as the founder of the Xia Dynasty.

Among Yu’s numerous contributions, his efforts in flood control and territorial administration, collectively referred to as “Yu’s Tracks,” stand out as his most celebrated in early archives. The Shangshu admonishes the descendants of King Wen of Zhou to maintain military readiness, ensuring their dominion matched the extent of “Yu’s Tracks,” encompassing all lands to the sea. Similar sentiments are echoed in later bronze inscriptions.

While the inscriptions on the Xu vessel of Duke Sui place the earliest records of Yu no earlier than the Western Zhou period—chronologically distant from Yu himself—it is common for later evidence to corroborate earlier traditions. Scholar Du Yong argues that the reason later evidence is used to corroborate earlier traditions lies in China’s long-standing emphasis on recording and preserving history, coupled with its system of official historiographers. This tradition ensured that even ancient civilizations, which lacked written records, were able to pass down their history. While certain details may have been distorted over time, the fundamental framework and key figures are not fabrications, but are rooted in historical reality.

Yu in archaeological evidence

Advances in interdisciplinary methods have made archaeology one of the fastest-growing fields in the humanities, yielding discoveries that further illuminate Yu’s story.

The story of Yu and his father, Gun, both tasked with flood control, is widely known. The Classic of Mountains and Seas records: “The great flood rose to Heaven, and Gun stole the divine soil from the Heavenly Emperor to block the floodwaters, defying the emperor’s command. In response, the Heavenly Emperor ordered Zhu Rong to execute Gun near Mount Feather. After Gun’s death, his body gave birth to Yu. The Heavenly Emperor then commanded Yu to lead his people in using earth to stabilize the Nine Regions and control the flood. Yu adopted the method of channeling and diverting the waters, successfully taming the flood and bringing stability.”

In 2016, Wu Qinglong, a research fellow at Nanjing Normal University, published a report in Science titled “Outburst Flood in 1920 BCE Supports Historicity of China’s Great Flood and the Xia Dynasty.” This study identified massive flooding around 1900 BCE in the upper Yellow River’s Jishi Gorge, caused by earthquake-induced landslide dams. The subsequent dam breaches resulted in catastrophic flooding downstream, lending scientific credence to the legend of Gun and Yu’s flood control efforts.

Simultaneously, research on the stalagmites in Wuya Cave, Gansu Province, pinpointed extreme rainfall events on the Loess Plateau around 4000 years (±48 years) ago, which may have lasted approximately 20 years. These prolonged rains on the upper reaches of the Yellow River likely caused persistent flooding downstream. Notably, the date of 4000±48 a BP aligns closely with the year 2070 BCE (4020 a BP) proposed by the Xia-Shang-Zhou Chronology Project as the founding of the Xia Dynasty. Furthermore, in terms of flood control, Gun spent 9 years and Yu spent 13 years, totaling 22 years of flood management. This corresponds closely to the 20-year period of intense rainfall identified in studies. This research not only enhances the objectivity of the Gun-Yu flood control narrative but also, to some extent, supports the historical authenticity of the Xia Dynasty.

According to the ancient texts Zuozhuan and Shuangshu, Yu’s achievements culminated in the famed gathering of regional lords at Mount Tu after flood control, where he solidified his leadership and married. Mount Tu, therefore, holds dual significance as both the site of Yu’s political consolidation and his familial legacy. However, for centuries, there have been significant divergences in the scholarly examination of the “Yu’s Assembly at Mount Tu” event.

In 2006, excavations began in Yuhui Village, south of Mount Tu in modern-day Bengbu, Anhui. Over the course of five years, archaeologists uncovered a prehistoric site spanning 500,000 square meters, dating to the late Longshan Culture—contemporaneous with Yu’s era. The site is believed to be a large ritual complex. Numerous one-time-use ritual artifacts and simple shed-like structures were unearthed at the site, which was in use for a period spanning one to two centuries. Professor Wang Zhenzhong believes that if the sites one-to-two-century use duration is linked to the local population, then its temporary nature is very likely to be closely associated with the legendary Yu’s Assembly at Mount Tu.

According to ancient texts, conflicts between the Central Plains tribes and the Sanmiao tribes had already occurred multiple times during the reigns of Yao and Shun [legendry rulers predating Yu]. By Yu’s time, these conflicts had escalated into more intense warfare. This war appears to have been a sudden attack launched by Yu against the Sanmiao under the unusual celestial phenomena of a solar eclipse and a rain of blood. After the war, the Sanmiao were “suppressed and extinguished, leaving no successors in later generations” (Shangshu).

Archaeological evidence indicates that around 4,500 years ago, during the late Shijiahe culture, with the resurgence and prosperity of Central Plains culture, the Central Plains Longshan culture continuously expanded southward. In a relatively short period, it not only reclaimed regions in northwestern Hubei and southwestern Henan, which had been occupied by the Qijialing culture’s northward expansion, but also pushed further south along the Han River valley into the Jianghan Plain. This reversed the developmental direction of Neolithic cultures in the middle Yangtze River region, giving rise to a new archaeological culture with characteristics and cultural connotations similar to the Wangwan Phase III culture, referred to as the “Post-Shijiahe Culture.”

Regarding the historical background of this cultural transition, scholars believe it is linked to the legendary account of “Yu’s campaign against the Sanmiao tribes.” They argue that after Yu’s conquest, the Sanmiao declined, and the Shijiahe culture was replaced by the Central Plains Longshan culture.

Further conclusions

Yu remains shrouded in mystery due to the diversity and complexity of pre-Qin historical records. However, thanks to research in archaeology and natural sciences, we now have a clearer understanding that the seemingly bizarre or absurd accounts in ancient texts were not baseless, but rather reflect the distinct characteristics of narratives from different eras and sources.

Before the advent of written characters, the preservation of ancient history largely depended on oral transmission by historiographers. Although some details may have been distorted over time, the basic framework of history and major figures remained consistent. According to Du Yong, after Confucius established private schools, scholarly cultivation gradually spread downwards, allowing more people to access education and engage in scholarly discussions. The dissemination of earlier historical information was thus significantly broadened. Moreover, during the intense social upheaval of the Warring States period, many scholars, eager to offer solutions to societal problems, turned to earlier history and debates over various schools of thought in support of their proposals. As James Frazer pointed out, the Warring States period was not only the age of the rise of rationality and the retreat of ignorance; parallel to this trend was another movement of irrationalism, which featured the mythologizing of historical figures. Under the influence of this movement, many historical figures underwent a transformation from human to deity, forming the characteristic late-stage mythology of ancient China.

Zhao Yanjiao is a research fellow from the Institute of History at Shandong Academy of Social Sciences.

Copyright©2023 CSSN All Rights Reserved