Lin’an as a cultural symbol in Southern Song literature

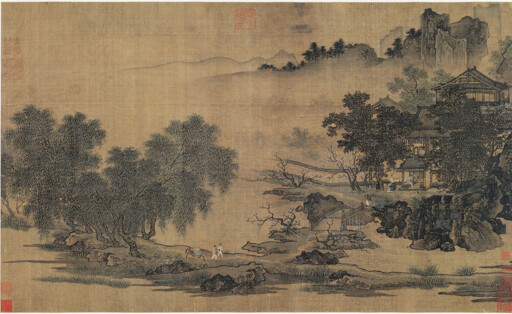

FILE PHOTO: One of the "Landscape of the Four Seasons" by Southern Song artist Liu Songnian, depicting the charm of the West Lake in Lin'an in four seasons

Among the capitals of ancient China, Lin’an [present-day Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province], the capital of the Southern Song Dynasty (1127—1279), holds a particularly distinctive place. As the political, economic, and cultural center of the relocated Song court, Lin’an embodied a fusion of Central Plains traditions with Wu-Yue culture from the Jiangnan region. It also coexisted with northern minority regimes such as the Jin and Yuan. From a broader temporal perspective, Lin’an was situated in the era of social transformation between the Tang and Song dynasties, foreshadowing the prosperous, affluent, and relatively open configuration of early modern society. The evolving structure of the capital and the shifting historical context provided fertile ground for the development of Southern Song urban literature.

Southern Song capital literature rendered Lin’an in vivid detail, capturing its urban layout, marketplace life, and natural scenery. The city’s structural framework was most clearly recorded in the so-called “Three Gazetteers of Lin’an”: the Qiandao Lin’an Zhi, the Chunyou Lin’an Zhi, and the Xianchun Lin’an Zhi. Compiled during the Southern Song, these were the earliest surviving local gazetteers of Hangzhou. Among them, the Xianchun Lin’an Zhi was the most detailed and best preserved. Its special section “Records of the Temporary Court” documented palaces, temples, ministries, schools, Daoist establishments, and gardens, accompanied by four maps—of the palace city, the capital, Zhejiang, and West Lake—that sketched the layout of Lin’an’s urban form.

The texture of daily life was vividly captured in urban miscellanies such as Mengliang Lu (The Notes of Bianliang Dreams), Ducheng Jisheng (Record of the Splendors of the Capital), and Wulin Jiushi (Reminiscences of Wulin). These works not only recorded wards and streets in detail, but also painted intricate portraits of marketplace life and everyday scenes, providing the very fabric of Lin’an’s image. Complementing this was the literary celebration of West Lake, which became the quintessential emblem of Lin’an’s natural beauty. The lake, described as “ever enchanting in light or heavy makeup,” appeared in diverse guises in the writings of Southern Song literati. Some even established poetry societies on its banks, turning West Lake into both a literary subject and a social space.

Southern Song capital literature offered a comprehensive portrayal of daily life across social classes, highlighting Lin’an’s distinctive lifestyle and infusing the city with a sense of intimacy. Miscellanies enumerate various trades, reflecting economic prosperity; describe festivals such as the Lantern Festival, Qingming, and the Dragon Boat Festival, showing the endurance of cultural traditions; and record entertainments, revealing the aesthetic tastes and consumer culture of the urban populace.

Court ceremonies, in which commoners were allowed to participate as spectators, were also documented. Scholar-officials themselves moved fluidly between public duty and private leisure. Yang Wanli, serving as lecturer to the Crown Prince, passed through the flower market by the northern palace gate and was captivated by the beauty of peonies and surprise lilies, exclaiming, “A momentary glance at this sea of red—what a reward for a second year in the capital city.” In contrast, Fan Chengda, weary from official burdens, lamented, “The nine thoroughfares’ dust stains my robe; beyond the Qiantang Gate lies a garden.” For him, the serene landscapes of West Lake offered brief respite and spiritual cleansing. Such writings endowed Lin’an’s image with dimensionality, much like delineating the speech and behavior of a living person, imbuing the city with vitality.

The literature of Lin’an was suffused with the complex emotions of its inhabitants, granting the city a rich affective dimension. Above all was the reluctant southward migration of the Song court [In 1127, the Jurchen–led Jin Dynasty invaded northern China, capturing the Song capital of Kaifeng, forcing the Song court to flee south, eventually establishing a new capital at Lin’an], and the yearning to recover the Central Plains. The Song-Jin peace accords brought temporary stability, enabling the flourishing of the new capital. Yet beneath this prosperity lay a constant undercurrent of crisis. The famous line—“The fragrant spring breeze leaves travelers drunk, so that they mistake Hangzhou for Bianzhou,” which expresses a momentary confusion or nostalgic longing for the northern capital Bianjing—encapsulates the paradox of simultaneous ease and unease. This tension produced conflicted emotions among visiting scholars.

With the fall of the Southern Song, Lin’an assumed the status of a “former capital.” Zhang Yan mournfully described West Lake as “Hidden amid a thousand shades of green, the banks of Xiling Bridge once thronged with lively crowds; now, only a wisp of desolate evening smoke lingers.” Such sorrowful scenes marked the final, tear-stained chapter of Southern Song capital literature.

Zhou Jianzhi is a professor from the College of Chinese Language and Literature at Beijin Normal University.

Copyright©2023 CSSN All Rights Reserved