The interweaving of word and image in ancient Chinese art

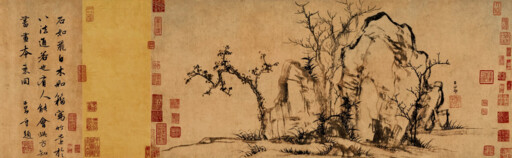

FILE PHOTO: “Elegant Rocks and Sparse Bamboo” by the Yuan artist Zhao Mengfu

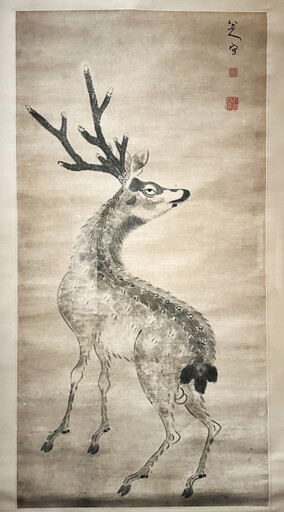

“Deer” by the early Qing artist Bada Shanren. The eyes of animals in his paintings are one of his most striking and recognizable features: bulging, staring, sometimes rolling upward, carrying a sense of alienation, mockery, or hidden sorrow — his signature psychological undertone. Photo: Ren Guanhong/CSST

The theory of “calligraphy and painting as one” [an idea emphasizing that calligraphy and painting share the same essence], first advanced by the Tang Dynasty art critic Zhang Yanyuan, sought to reveal the intrinsic commonality between calligraphy and painting in their fundamental attributes, aesthetic paradigms, and cultural psychology. By the Yuan Dynasty, calligraphers and painters had organically integrated poetry, calligraphy, and painting, extending the theory beyond aesthetics to a broader cultural significance. Artists emphasized expressing inner sentiments through the acts of “writing and painting.” Thereafter, as calligraphy and painting permeated and influenced one another, they merged into a unified tradition that helped shape the distinctive aesthetic ideals and cultural spirit of the Chinese nation.

Artistic connotations and technical fusion of calligraphy and painting

As early as antiquity, “In the early period, calligraphy and painting were interconnected in form and had not yet fully diverged, both relying on concise brushstrokes to depict objects” (Records of Historical Famous Paintings, a book by Zhang Yanyuan). Hexagrams, characters, and paintings were all collectively termed “images,” indicating that writing and painting jointly served as vehicles of visual expression and information transmission in early human culture. Later, in pursuit of more precise and efficient means to convey abstract thought and emotion, people developed “calligraphy,” while to vividly reproduce natural and cultural scenes, they created “painting.” Thus it was said: “When meaning cannot be conveyed, there is writing; when form cannot be shown, there is painting” (Records of Historical Famous Paintings). The differentiation between writing and painting not only reflected humanity’s pursuit of diverse modes of expression but also marked the emergence of specialization and refinement in the arts.

Yet writing and painting were never completely separate. From an aesthetic perspective, they remained “different in name yet one in essence.” This suggests that while distinct in form and terminology, calligraphy and painting share profound affinities in artistic nature, aesthetic pursuit, and cultural function. Together, they constitute a vital branch of visual art, showcasing creativity and aesthetic intelligence.

Later generations of artists, building on Zhang Yanyuan’s theory, further elaborated this artistic proposition. In the Northern Song Dynasty, art critic Guo Ruoxu asserted in Experiences in Painting that “the brushwork for painting garments, trees, and rocks is entirely akin to calligraphy,” suggesting the essential unity of technique and expression in both arts. Yuan Dynasty painters developed this view more vividly. A poem inscribed on “Elegant Rocks and Sparse Bamboo” [a painting by the Yuan artist Zhao Mengfu] declared: “Depicting rocks is akin to writing in the fei bai style [a calligraphic technique characterized by partially broken strokes that reveal the brush’s texture], while depicting trees resembles writing in the zhou script [an ancient large-seal style]. To paint bamboo, one must first comprehend the ‘Eight Methods of Calligraphy’ [the fundamental brush techniques codified in Chinese writing]. Anyone who can grasp this principle will recognize that painting and calligraphy are, in essence, one and the same.” Through these vivid metaphors, painters and calligraphers linked calligraphic techniques such as fei bai and zhou script to pictorial elements like rocks, bamboo, and trees, thereby underscoring the intrinsic connection between calligraphy and painting and further deepening the meaning of “calligraphy and painting as one.”

Ke Jiusi, a Yuan painter and calligrapher, also observed: “When painting tree trunks, one employs the brush of seal script, producing lines that are thick, rounded, and imbued with an archaic gravity. Tree branches are rendered with the methods of cursive script, their strokes flowing continuously with lively variation. Leaves are drawn with the brush techniques of clerical script (bafen style), giving the strokes a dynamic and expressive quality. One may also adopt the slanting brushstroke of the great Tang calligrapher Yan Zhenqing, emphasizing strength and vigor. In depicting trees and rocks, painters make use of brush methods reminiscent of the ‘hairpin stroke’ (resembling the parallel traces of hairpins) and the ‘leaking-roof mark’ (like the traces left by dripping water from a roof), thereby conveying solidity of texture and a natural rhythm.”

By aligning pictorial elements with calligraphic strokes, Ke reinforced the principle of technical integration between calligraphy and painting. By the Yuan period at the latest, the theory of “calligraphy and painting as one” had already gained wide consensus among artists, becoming a creative principle. Inspired by this theory, successive generations explored innovative modes of integration, thereby advancing the development of Chinese art.

Expressive sentiment and concept of ‘Writing Painting’

Both calligraphy and painting embody the artist’s unique emotions and sentiments, articulating their inner world. Zhang Yanyuan’s proposition of “calligraphy and painting as one” revealed their shared artistic essence, endowing both forms with richer and more diverse capacity for emotional expression.

Before the Northern Song, painting emphasized the faithful representation of objective scenes, focusing on the “likeness in form.” During the Northern Song, however, it evolved from “emphasizing form” toward xie yi (写意, expressive or idea-based painting). By the Yuan Dynasty, “likeness in form” and realism had been relegated to secondary importance—painters placed greater emphasis on self-expression and the articulation of their own subjective sentiments. Consequently, xie yi became a defining feature of Yuan calligraphy and painting.

The Yuan understanding of xie yi carried both aesthetic and cultural significance. Aesthetically, calligraphy and painting demanded the same brushwork and linear mastery; painting was to be executed with the techniques of writing—“using calligraphy in painting”—thereby achieving a perfect integration of brush technique and pictorial expression. Culturally, it meant expressing one’s inner emotions through painting.

In his Treatise on Painting, the Yuan artist Tang Hou wrote: “Painting plum blossoms, bamboo, and orchids are not merely painting, but ‘writing.’ To ‘write’ plum, bamboo, or orchids is, in fact, to ‘write’ the heart, intention, and emotion. In other words, the ‘intention’ (意, yi) must be realized through ‘writing’ (写, xie). Xie yi does not aim at visual likeness; rather, it uses plum, bamboo, and orchids as vehicles to convey the spirit and emotional depth within the artist’s heart.” Thus, the concept of “writing painting” transcends purely aesthetic concerns, taking on a cultural dimension as a medium for expressing inner sentiment.

By the Yuan Dynasty, the notions of “calligraphy and painting as one” and “writing painting” (xie hua) had become major guiding principles of artistic creation. This approach continued into the Ming and Qing dynasties. In xie yi painting, Xu Wei was especially accomplished, while later artists such as Bada Shanren [a painter and calligrapher known for his highly expressive and unconventional style] and the Eight Eccentrics of Yangzhou [a group of eight painters known for their unconventional styles and disregard for orthodox norms] elevated it to new heights.

Embodiment of humanistic character

Having undergone preliminary development in the Tang and Song, by the Yuan Dynasty the theory of “calligraphy and painting as one” had transcended its original framework, evolving into a richer cultural proposition. Yuan artists not only emphasized “bringing calligraphy into painting” and combining poetry and painting, but also stressed the embodiment of personal character.

The aesthetic standard of yi (逸, untrammeled) as an independent criterion first emerged in the Tang Dynasty. Art theorist Zhu Jingxuan, in his Record of Famous Painters of the Tang, was among the first to use yi in evaluating painting. By the Song Dynasty, its aesthetic value had been greatly elevated. Fundamentally, this stems from the fact that a work of yi could transcend the tangible and finite to reach the intangible and infinite, aligning closely with the artist’s expressive intent.

The Yuan Dynasty inherited the Song tradition, and yi reached its fullest expression in painting. Yuan painters no longer adhered strictly to precise depiction of objects, nor did they deliberately pursue likeness. Instead, they emphasized a spiritual and lyrical integration with nature, creating works that convey a sense of depth, delicacy, subtlety, and refinement. In artistic creation, conveying artistic conception far outweighed faithful visual rendering. This pursuit of yi reflected the artist’s concern for personal character and spirit, embodying the literati’s serene and detached mindset in the Yuan period.

The Yuan painters’ admiration for yi developed into a major cultural trend by the Ming and Qing dynasties. In the works of Yuan masters such as Ni Zan, the pursuit of yi coexisted with a certain degree of fidelity to natural forms. By the Ming and Qing periods, however, artists such as Shi Tao, Bada Shanren, and the Eight Eccentrics of Yangzhou further abandoned the concept of likeness, allowing personal inspiration and emotional expression to dominate the creative process. In their works, individual sentiment, mood, and philosophical reflection flowed freely, and the artist’s unique character was expressed more fully than ever before. This transformation not only propelled Chinese painting toward greater freedom and diversity but also allowed the aesthetic pursuit of yi to flourish brilliantly in Ming and Qing art.

Liu Xiuzhe is a lecturer at the Literature College of Heilongjiang University.

Copyright©2023 CSSN All Rights Reserved