Sanxingdui reveals shared origins of Chinese ritual civilization

Various Zhang (jade blades) of Sanxingdui Photo: Lu Hang/CSST

Bronze phoenix bird unearthed at Sanxingdui Photo: Lu Hang/CSST

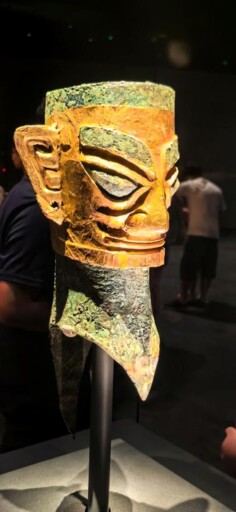

A bronze head with a gold mask Photo: Lu Hang/CSST

“Radiocarbon dating shows that No. 3, 4, 6, and 8 sacrificial pits of the Sanxingdui site were buried between 1201 and 1012 BCE with a 95.4% probability, corresponding to the late Shang Dynasty (c. 16th–11th century BCE). Fragments of identical artifacts that can be reassembled were found in No. 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, and 8 pits, indicating that they were buried in the same era,” said Ran Honglin, director of the Sanxingdui Site workstation at the Sichuan Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology and deputy curator of the Sanxingdui Museum, presenting the latest multidisciplinary research results on the site at the 2025 Sanxingdui Forum. These findings provide key evidence for establishing a precise chronological framework for the Sanxingdui site and sacrificial pits.

The dating of Sanxingdui’s sacrificial pits has long been a central focus for scholars and the public alike. Radiocarbon data indicate that the bronze-filled pits date from roughly 3,226 to 3,037 years ago, a period when both the Yinxu site in the Yellow River basin and Sanxingdui in the upper Yangtze were flourishing during the late Shang Dynasty. This raises an enduring question: Did the ancient Shu kingdom of Sanxingdui maintain contact with the Shang or Western Zhou dynasties in the Central Plains?

A distinct cultural identity

The civilizations of Xia (c. 21st–16th century BCE), Shang, and Zhou (c. 11th century–256 BCE)—representing China’s Bronze Age—shared a defining feature: a ritual system centered on bronze vessels symbolizing state power and hierarchical order. This ritual system of bronze vessels not only marked the formation of early Chinese civilization but also profoundly influenced the broader cultural development of East Asia. According to Huo Wei, a professor from the School of History and Culture at Sichuan University, archaeological discoveries at the Sanxingdui site reached a peak with the excavation of two major sacrificial pits in 1986. The finds included colossal bronze human figures, enigmatic bronze masks, bronze heads with varied hairstyles overlaid with gold masks, towering bronze “divine trees,” and gold scepters—all reflecting a unique and sophisticated cultural style. Subsequent discoveries at the Jinsha and Shi’erqiao sites in Chengdu, Sichuan Province, further confirmed a cohesive Sanxingdui cultural system, enriching our understanding of East Asian Bronze Age civilizations.

Situated in Guanghan City on the Chengdu Plain, the Sanxingdui site covers approximately 12 square kilometers, with a 4-square-kilometer core city area. Apart from a natural river to the north, the ancient city was enclosed on three sides by rammed-earth walls, with clearly defined functional zones inside. Excavations of eight sacrificial pits, together with large architectural remains at Qingguanshan and multiple rammed-earth “small cities” from different periods, have led scholars to regard Sanxingdui as the crowning achievement of ancient Shu civilization. Sun Hua, a professor from the School of Archaeology and Museology at Peking University and academic dean of the Sanxingdui Research Institute, explained that the site is a large-scale settlement with long occupation and broad spatial range, encompassing three major developmental periods: the Baodun culture, the Sanxingdui culture, and the Shi’erqiao culture. These periods are linked by continuity yet marked by notable differences. During the Baodun period, rival communities built walled settlements, but Sanxingdui ultimately annexed them, emerging as the dominant central settlement of the plain.

“Major transformations occurred at the beginning of Sanxingdui’s third phase, which caused the Sanxingdui city to decline from a national capital to an ordinary city. During this transition, wars for the capital might have occurred,” Sun speculated. “In these wars, parts of Sanxingdui’s city walls were destroyed, the water system was altered, the original functions of the large building areas were lost, and the religious sacrificial sites ceased to exist.” Thereafter, residents concentrated in the small northwestern town of Sanxingdui, while others migrated elsewhere, thus giving rise to the proliferation of Shi’erqiao-phase settlements on the Chengdu Plain and across the Sichuan Basin and ushering in a new stage of social development.

Technical innovation and localized expression

Sanxingdui bronzes include vessels resembling zun and lei (both ritual wine vessels) from the Central Plains, though no ding (ritual tripod vessels) have yet been discovered. Huo noted that there is currently no evidence to suggest an intuitive imitation of the Central Plains’ “display of ding” system (a set of ding vessles comprising an odd number with identical shapes and progressively decreasing sizes) in the Sanxingdui civilization. However, these bronze zun and lei largely adopt the forms of similar Central Plains vessels, but decorated with distinctly local motifs such as dragons, tigers, birds, large-eyed beast faces, and other enigmatic animal images. These styles are also closely related to the bronze system of southern China.

“The ancestors of Sanxingdui were not completely unaware of the Central Plains bronze ritual vessel system,” Huo said. For example, a bronze figure holding a zun over its head suggests the vessel’s high ceremonial status, comparable to its use in Central Plains ritual contexts. Some Sanxingdui zun and lei contained small jade or shell artifacts, and one newly excavated altar base featured a small kneeling bronze figure carrying a lei on its back, perhaps representing the offering of the most precious ritual goods—wine, meat, jade, or shells—at the very center of the altar. These examples indicate deep reverence the Sanxingdui people held for zun and lei, regarded as among the most ritually significant “national treasures” in the Central Plains bronze civilization.

Some Sanxingdui bronzes were cast using techniques identical to those in the Central Plains. Previous studies have detected highly radiogenic lead isotopes in bronzes unearthed at Yinxu. After testing 53 bronze samples from the Sanxingdui sacrificial pits, researchers found that as many as 50 belonged to this high-radiogenic lead category, indicating metallurgical interaction and exchange between the Central Plains and the upper Yangtze. According to Huo, this suggests that Sanxingdui likely absorbed diverse surrounding cultural influences, standing as an early symbol of East-West interaction within China.

Shared origins of ritual civilization

Beyond bronzes, Sanxingdui has yielded large quantities of pottery, jade, and stone artifacts. Jade relics include zhang (jade blades), bi (jade discs with circular holes in the center), and cong (tube-shaped jade), which are almost identical to those excavated at Erlitou and Yinxu, all serving as sacrificial ritual instruments. In early Chinese civilization, jade complemented bronze as a key symbol of ritual order. The form of Sanxingdui zhang closely resembles that of the Central Plains and most parts of China. The use of jade, symbolizing communication between heaven and earth, deity and human, originated in the Neolithic period and formed a distinct ritual system in early Chinese civilization—a special cultural phenomenon not found in other ancient civilizations of the world.

Deng Cong, a professor from the School of Archaeology at Shandong University, has long studied yazhang (jade blades carved with teeth-like notches). He found that the earliest yazhang unearthed in China appeared over 4,000 years ago in Shandong and spread westward across the Yellow River basin. Around 3,600 years ago, they appeared in the middle Yellow River region, particularly at the Erlitou site, where a large number were found with a “dragon” transformation, which included a protruding “tooth” appearing on either side. About 3,300 years ago, this style spread south to the Sanxingdui and Jinsha sites, where the yazhang unearthed are predominantly dragon-tooth yazhang. In addition to dragon yazhang, these sites also yielded locally specific yazhang, which incorporated elements of phoenix culture. The Yangtze River basin and Lingnan (a region encompassing Guangdong, Hainan, Guangxi, and parts of Yunnan and Fujian) were centers of phoenix culture, with Sichuan located in the upper Yangtze. Similar artifacts have since been unearthed in Southeast Asia, including northern Vietnam. To Deng, this implies that the yazhang found in northern Vietnam were likely influenced by the ancient Shu culture.

The civilizations of Xia, Shang, and Zhou established a system centered on ritual. The people of Sanxingdui selectively adopted elements from this system, using ritual vessels in their own sacrificial ceremonies. While they abandoned the Central Plains’ “display of ding” system, they expressed reverence through other forms, such as kneeling figures holding zun vessels. These bronze ritual vessels can be seen in various sacred scenes adorning altars.

Huo concluded that the Sanxingdui bronze culture, located in the upper Yangtze and contemporaneous with the late Shang dynasty, corresponds to the ancient Shu civilization recorded in historical literature and legend. Although currently the chronology and periodization of the Sanxingdui bronze culture are difficult to match one-to-one with the legendary successive kings of the ancient Shu kingdom, this cultural system shares many commonalities with the Central Plains Shang bronze civilization. These commonalities are fully reflected in jades, the ritual vessel category among bronzes (such as zun and lei), the shapes and decorative motifs of bronze vessels, manufacturing techniques, and raw materials. This demonstrates a close and harmonious relationship between Sanxingdui and the Central Plains bronze civilizations. It also indicates that during the formation and development of the Xia, Shang, and Zhou civilizations, the Sanxingdui bronze civilization in the southwestern border was deeply influenced by the Central Plains bronze ritual system and can even be regarded as a member of the broader Central Plains civilization system.

Copyright©2023 CSSN All Rights Reserved