45 beans rewrite origins of East Asian agriculture

The carbonized adzuki beans unearthed at the Xiaogao site in Zibo, Shandong Province Photo: SDU

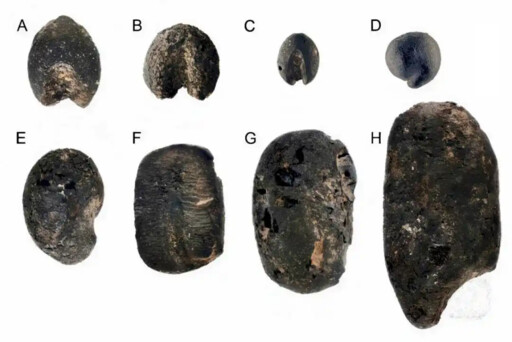

Archaeological samples of adzuki beans and modern adzuki beans Photo: SDU

Chinese scholars discover 9,000-year-old carbonized adzuki beansAt the Xiaogao site in Zibo, East China’s Shandong Province, 45 carbonized adzuki beans hid quietly under the soil for 9,000 years. Measuring just 2.3 millimeters long and 1.6 millimeters wide, these relics have resurfaced to rewrite the story of East Asian agriculture. In a recent article in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, an international research team led by Chinese scholars reported the discovery of these carbonized adzuki beans—dated to roughly 9,000 years ago—pushing back the origins of northern China’s millet-and-legume dryland farming system to the same period. Their findings challenge the “single-origin” narrative of crop domestication and provide compelling evidence for a multi-regional origin of adzuki beans, reshaping our understanding of how early agriculture took root across East Asia.

Major agricultural transitions in lower Yellow River basin

The Xiaogao site, situated on the alluvial plains at the northern foothills of the Tai-Yi Mountains, is a representative site of the Houli culture. In 2017, a joint archaeological team from the Shandong Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology and Shandong University (SDU) uncovered, beneath this seemingly ordinary stretch of land, a crucial chapter in the story of prehistoric Chinese agriculture.

“When we identified the carbonized adzuki beans in the ash pits and house remains, the entire laboratory was thrilled,” recalled Chen Xuexiang, a professor at SDU’s School of Archaeology and head of the research team. In the 600-square-meter cultural deposit, archaeologists systematically collected 891 flotation samples and identified some 32,000 carbonized plant remains, including foxtail millet, broomcorn millet, rice, soybeans—and notably, 45 carbonized adzuki beans.

These inconspicuous beans, unearthed alongside house foundations, ash pits, pottery, stone grinding slabs, and stone axes, sketch a vivid picture of life in the lower Yellow River region 9,000 years ago. Zhao Zhijun, a research fellow from the Institute of Archaeology at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences and distinguished professor at SDU, noted that the site’s importance extends far beyond the beans themselves. At this formative stage of agriculture in northern China, ancient communities still relied mainly on hunting and gathering but had begun cultivating crops and living in permanent dwellings. Similar structures dating to the same period have been discovered at the Sitai site in Shangyi, Hebei Province, jointly attesting to this pivotal transition.

The most compelling evidence comes from precise radiocarbon dating: Two beans yielded direct dates of between roughly 9,000 and 8,000 years ago. “This is 4,000 years earlier than previously discovered carbonized adzuki beans within China and 6,000 years earlier than carbonized adzuki beans with direct dating data,” Chen emphasized. “More importantly, the co-occurrence of these beans with foxtail millet, broomcorn millet, and soybeans confirms that by 9,000 years ago, the lower Yellow River region had already developed the earliest ‘cereal and legume’ composite cropping system in East Asia.”

For decades, international archaeological attention has focused largely on major crops such as wheat, maize, and rice. “This preference stems mainly from their core position in today’s human food system,” said Xinyi Liu, a professor from Washington University in St. Louis. “Yet historically, more than 5,000 plant species have entered the human diet. The loss of dietary and nutritional diversity has become one of the major challenges facing humanity today.” Research into the early domestication and cultivation history of legumes such as adzuki beans offers crucial insights into the historical trajectory of food diversity, regional differences in agriculture, and the sustainability of ancient farming systems.

Zhao further noted that the origin of legumes had long been a relatively weak area in Chinese archaeological studies of early agriculture. The latest findings on carbonized adzuki beans have attracted significant international attention, marking China’s growing participation in global academic dialogues on the origins of legume crops. The proposed “foxtail millet, broomcorn millet, and legume” dryland farming system offers a key new perspective for understanding the complexity and distinctiveness of East Asia’s agricultural origins.

Regional diversity of adzuki bean domestication

As one of East Asia’s most widely grown legumes, the adzuki bean plays a central role in regional diets and agricultural systems, prized for its nutritional value and nitrogen-fixing ability. Yet its initial domestication—when and where it occurred—has long been contested, remaining a major mystery in East Asian agricultural history.

In May this year, Science published a genetic study on modern adzuki bean populations, suggesting that domestication most likely occurred in Japan, with the introgression of Chinese wild varieties accounting for their complex genomic patterns. On that basis, some scholars even proposed a “single-origin” hypothesis. Yet the Xiaogao site tells a very different story. “As early as 9,000 years ago, people living along the Yellow River were already engaging in human selection of adzuki beans,” Chen said.

Although multiple centers of agricultural origin have long been acknowledged in theory, understanding the regional diversity and inherent dynamics of domestication still requires deeper study. A major advance in recent years has been a growing recognition of the long-term and cross-regional nature of domestication—challenging the traditional assumption that a species was domesticated rapidly within a single center.

In this study, the research team conducted a systematic comparison of adzuki bean remains from over 140 archaeological sites across East Asia. The morphological characteristics of the Xiaogao specimens proved particularly striking: Their average volume is significantly smaller than those found in contemporary and later Chinese sites and even smaller than their modern wild relatives, intuitively reflecting the morphological traits of the initial stage of adzuki bean domestication. The analysis also revealed regional differences in domestication timing. “The varying rates of domestication across regions were likely linked to differences in dietary preferences among populations,” Liu speculated. During the early phases of agricultural development, high mobility among communities and crops—and the resulting hybridization and environmental adaptation pressures—played crucial roles in shaping the domestication process.

The adzuki bean’s “East Asian case” provides another crucial example for this new theoretical framework of domestication. As Chen further explained, cross-regional comparative archaeological analysis confirms that adzuki bean domestication in East Asia was a prolonged, multi-centric, and complex process in which both cultural and environmental adaptation played pivotal roles.

Enhanced international cooperation needed

The Xiaogao study also stands as a model of international scientific collaboration, uniting scholars from China, the United States, Japan, and South Korea. “International cooperation offers great advantages in studying crop domestication,” Zhao stated. “As crop domestication is a global issue, researchers around the world share a common goal—to clarify the processes and dynamics behind the transformation of human production and lifestyle around 10,000 years ago.”

“We conducted a detailed comparison of data from more than 140 archaeological sites across East Asia,” Chen explained. “Throughout this process, close collaboration among scholars from different countries made it possible to align and interpret the data effectively.” The team also integrated multiple cutting-edge techniques, combining archaeological evidence with molecular genetics data to build a more comprehensive model of adzuki bean domestication and diffusion.

This collaboration extended beyond data sharing to include the genuine exchange and integration of academic traditions. Liu observed, “In anthropology and archaeology, the perspective of the Other often reminds researchers to notice what they might otherwise take for granted, breaking through habitual ways of thinking. A deeper understanding of East Asian agriculture and early societies helps us reexamine the ancient world from fresh perspectives.”

In the 20th century, research on the Fertile Crescent foothill zone in Southwest Asia established the foundational theoretical and practical paradigm for studying the origins of agriculture worldwide. But has this paradigm, to some extent, also constrained our imagination about the diversity of early agricultural systems? This is a question worth pondering. “In recent years, major advances in East Asian agricultural origin studies have significantly broadened our horizons. We now look forward to writing a truly global history of agriculture that integrates both Eastern and Western perspectives,” Liu proposed.

Looking ahead, Chinese academia still faces significant challenges in advancing the study of East Asian agricultural origins. Zhao acknowledged that domestic scholarship remains limited in scope and output. Building on this breakthrough discovery, the team has already mapped out future research directions, advancing archaeological studies of agricultural origins and diffusion within the broader context of ancient Northeast Asian civilizations. Continued work of this kind is essential for constructing a complete narrative of East Asian agricultural origins.

From Shandong’s Xiaogao site to Japan’s Jomon sites, from the Yellow River basin to the Korean Peninsula, the domestication story of adzuki beans mirrors the intricate tapestry of humanity’s shared agricultural evolution. In the fields of the future, the diversity of crops, the inclusiveness of cultures, and the continuity of civilization will continue to intertwine—painting an even richer civilizational landscape.

Copyright©2023 CSSN All Rights Reserved