Pictographic writing decodes genesis of Chinese characters

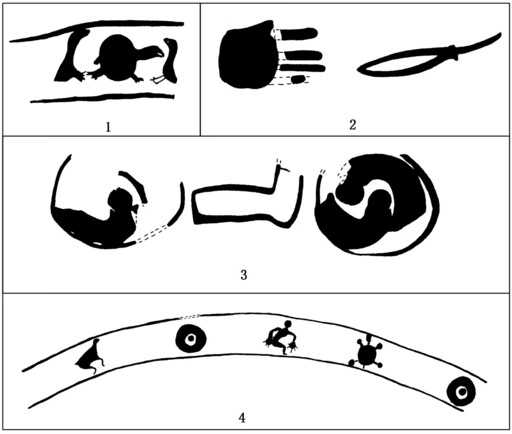

Painted pottery patterns unearthed at the Hongshanmiao site illustrate stories, commemorate events, and serve as records of early life. Photo: Yuan Guangkuo

FILE PHOTO: The Liangzhu culture black pottery jar unearthed in Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province

Writing is a defining marker of civilization. As the carrier of Chinese civilization, Chinese characters have played a decisive role in cultural transmission and development. Their continuous, orderly evolution has shaped the enduring vitality of Chinese civilization, which has flourished unbroken for more than five millennia. Regarding the origin and early forms of Chinese writing, both paleographers and archaeologists, drawing on evidence from their respective fields, have identified a crucial link in the development of the Chinese script system—pictographic writing. Meaning “representing forms,” pictography was the primary method of character creation in early China. Before the mature writing system of the early Shang Dynasty (c. 16th–11th century BCE) emerged, Chinese characters had already undergone a long and gradual process of evolution.

Early explorations in Peiligang era

Beyond paleography, an expanding body of archaeological evidence provides valuable clues to the origins and development of early writing. Archaeologists have uncovered thousands of inscribed symbols at sites such as Jiahu in Wuyang, Henan; Hongshanmiao in Ruzhou, Henan; Shuangdun in Bengbu, Anhui; Lingyanghe in Juxian and Dinggong in Zouping, Shandong; Shijiahe in Hubei; Liangzhu in Zhejiang; and Taosi in Shanxi. These early inscriptions outline three major stages in the evolution of pictographic writing: the exploratory stage (Peiligang culture, c. 8,000–7,000 years ago), the developmental stage (Yangshao culture, c. 6,000–5,000 years ago), and the transitional stage (Longshan culture, c. 5,000–4,000 years ago).

The exploratory stage is an indispensable link in tracing the lineage of Chinese characters, revealing the complex interplay among writing, thought, and society in early Chinese civilization. Specifically, discoveries at the Jiahu site indicate that as early as 8,000 years ago, during the Peiligang period, ritual activities such as sacrificial ceremonies had already appeared, with shamanic groups gradually forming a distinct social class. The turtle-shell inscriptions unearthed at Jiahu not only preserve traces of divination and ritual practice but also offer valuable clues to the development of early pictographic writing. These carvings include graphic symbols resembling the sun and hieroglyphs corresponding to “一” (one), “二” (two), “目” (eye), and “日” (sun). The engraved symbols feature clear strokes and structured layers of composition, exhibiting the basic characteristics of proto-writing.

Over 600 incised symbols were discovered at the Shuangdun site in Bengbu, Anhui. Excavators classified them into two categories—pictographic and geometric—with a total of 110 pictographic symbols, including representations of the sun, fish, pig, deer, and other animal and plant motifs. These symbols exhibit distinct regional characteristics, with similar markings discovered at the Houjiazhai site in Dingyuan, Anhui, in the Huai River basin, and the Dingshadi site in Jurong, Jiangsu, in the lower Yangtze River basin. Within a certain geographic span, the symbolic systems and pictorial styles display notable consistency. This assemblage of engraved symbols constitutes crucial empirical evidence for studying the origins of Chinese writing, possessing several clear features of continuity and evolution. First, their sheer quantity and variety stand out. The ancestors who lived 7,000 years ago used realistic depictions—such as animal and plant images—for basic record-keeping, while also beginning to employ simplified abstract lines, marking a key transition from pictures to symbols and from concrete to abstract. Second, symbol combinations pairing geometric lines with pictorial elements are observed, demonstrating a major cognitive leap—from single-layered ideographical expression to compound representation. Third, certain Shuangdun symbols bear connections to earlier markings found at the Jiahu site, offering important evidence of the broad spatial and temporal development trajectory of early pictographic writing.

Gradual progression in Yangshao era

Entering the developmental stage, engraved or painted patterns on pottery have been found in Yangshao, Dawenkou, Daxi, and Liangzhu cultures. These symbols are widely distributed across China and show strong regional diversity: The Central Plains, the Haidai region, and the Taihu basin each display distinct stylistic traits. Archaeological evidence suggests that some pottery symbols were closely linked to local totemic beliefs: In the central Shaanxi plain, symbols from the Yangshao culture often depict fish motifs and the widely revered “human-faced fish pattern.” Pottery symbols from the Dawenkou culture in Shandong often feature the regionally worshipped “sun-moon-mountain.” In the lower Yangtze basin, the Liangzhu culture is characterized by “beast-face” totems. These motifs, repeatedly used and widely circulated within their regions, embody shared cultural identities and communal beliefs. Other distinct pictorial symbols have also been unearthed. Yangshao painted pottery patterns from the Hongshanmiao and Yancun sites in central Henan often display narrative, commemorative, or record-keeping functions. Some Hongshanmiao designs depict scenes such as birds and the sun, human hands and farm tools, fish combinations, and compositions featuring deer, turtles, and human figures, as well as sun–moon combinations.

Additionally, numerous incised patterns have been found on pottery from the Liangzhu culture in the lower Yangtze River basin, such as the black pottery jar unearthed in Hangzhou, Zhejiang and the pottery zun (ritual wine vessels) from the Guangfulin site in Shanghai. These early pictographic symbols from the developmental stage primarily depict humans, animals, and celestial bodies such as the sun and moon. Their content primarily records early human hunting, warfare, and ritual activities, featuring a strong documentary nature. The imagery is clear and purposeful, capable of conveying relatively complex scenes and stories, demonstrating a pronounced ideographic function. This indicates that Yangshao pictographic writing had developed beyond the rudimentary markings of the Peiligang era, gradually acquiring combinatory, syntactic, and ideographic richness.

Qualitative leap in Longshan era

The Longshan culture period heralded the beginning of the transformative stage. Pictographic writing from this era still featured many individual symbols and narrative drawings, yet increasingly complex and organized sentence-like compositions began to appear, reflecting more advanced semantic expression. The engraved symbols unearthed from the Shijiahe culture are most abundant at the Xiaojiawuji and Dengjiawan sites in Tianmen, Hubei. Most of these inscriptions were engraved on pottery. In addition to single pictographs such as “sickle” and “cup,” more elaborate designs depicting ceremonial acts, possibly involving wine offerings to deities, have been unearthed. During this stage, several sites produced sentence-like inscriptions. The earliest examples include the Liangzhu pottery inscriptions, followed by those from the Dinggong site of Longshan culture and the Longqiuzhuang site, as well as the vermilion-painted pottery inscriptions from the Taosi site. At the Dinggong site, a pottery shard was found with 11 inscribed symbols, which some scholars believe represent a syntactic structure. At the Longqiuzhuang site in Gaoyou, Jiangsu, pottery fragments with eight neatly arranged symbols—composed of straight lines and resembling side-viewed animal forms—illustrate an intermediate stage in the transition from pictorial to abstract symbols.

The Longshan culture period marked a critical turning point in the history of Chinese writing, witnessing a qualitative leap from pictorial symbols to a genuine writing system. In form, these written symbols shifted from concrete pictorial representations to abstract lines. This process of abstraction is one of the hallmarks of mature writing, signifying that symbols had broken free from direct imitation of tangible objects and acquired a stronger capacity for conceptual expression. Structurally, writing evolved from isolated symbols or sequential pictorial scenes to coherent syntactic compositions. In terms of writing tools and methods, discoveries at the Taosi site revealed the use of a specialized writing brush, indicating that scribes had already mastered advanced writing techniques. Such inscriptions transcend simple carvings and belong to an early writing system, representing a crucial milestone in the evolution of pictographic script. Together, these findings indicate that China had formally entered the era of writing.

Continuity with Shang script systems

In early Chinese civilization, the development of pictographic writing maintained an intricate and continuous cultural lineage with the script systems of the Shang and Zhou (c. 11th century–256 BCE) dynasties. Particularly, the structural origins of Shang bronze and oracle bone inscriptions can be traced back to the incised symbols of the distant Neolithic Age. Many of the individual symbols from Neolithic cultures—such as clan emblems and ritual or shamanic symbols—served both as records of daily life and as manifestations of a cosmic, image-based mode of thought that sought to imitate and interpret the natural world. This mode of thinking was directly inherited by the hieroglyphs of the Shang and Zhou periods. For instance, the “pig” and “fish” symbols unearthed at the Shuangdun site exhibit simple yet vivid line forms that closely resemble the hieroglyphs of the Shang Dynasty.

The pictorial legacy of early writing remained vividly present in Shang oracle bone and bronze inscriptions, including pictographs of animals like fish, pigs, and horses, as well as utensils such as ding and jue (both ritual tripod vessels). Some symbols used physical variation to convey abstract concepts—like a severed head symbolizing death—while others depicted events through dynamic scenes such as a person leading an ox to indicate “to lead,” or misaligned wheels to represent a damaged vehicle. These examples serve as living fossils of the transition from pictorial to fully developed script. In Yinxu oracle bone inscriptions, some characters still use proto-writing representing phrase or sentence components. For instance, some divination inscriptions depict broken chariot axles or vehicles with a broken shaft through pictorial signs.

From the Neolithic to the Bronze Age, from pottery to bronze inscriptions, from concrete depictions to abstract formations, pictographic writing—the earliest stage in the development of Chinese characters—underwent a long process of evolution. It gradually advanced from individual symbols to structured syntactic expression, marking proto-writing’s revolutionary leap from isolated sign-making to a systematic language. This transformation went beyond simple pictorial record-keeping, acquiring the essential functional features of primary writing. The wealth of unearthed pottery inscriptions together forms a developmental chronicle of early Chinese script. These written symbols outline the diverse yet unified geographical landscape of early civilization, record the ritual and warlike practices of ancient communities, and bear witness to the continuous developmental trajectory of pictographic writing.

Yuan Guangkuo is a professor from the School of History at Capital Normal University.

Copyright©2023 CSSN All Rights Reserved