Chinese logic featuring historical continuity and cross-cultural exchanges

In modern era, against the backdrop of the “eastward spread of Western learning,” Western traditional logic entered China alongside modern Western knowledge systems. Photo: TUCHONG

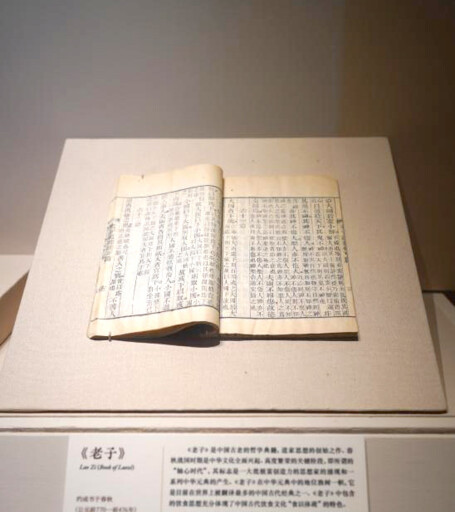

Tao Te Ching, a classic of Taoism, displayed at the National Museum of China in Beijing Photo: Yang Lanan/CSST

In the history of human thought, the systems of logic that originated in ancient Greece, ancient India, and China are widely regarded as the three major sources of world logic. During the early periods in which Chinese and foreign intellectual traditions emerged, these three forms of logic developed relatively independently along parallel trajectories, each serving as a foundational pillar supporting its own knowledge system.

Historical continuity

The pre-Qin (prior to 221 BCE) era witnessed profound upheavals in China’s social structures and institutions, a turbulence that stimulated remarkable intellectual flourishing and development. It was in this crucible that the foundations of traditional Chinese thought and culture first crystallized. Nearly all major theoretical concerns and doctrinal lineages in the history of Chinese thought can be traced back to the classical texts of the pre-Qin philosophers.

Zhengming—often translated as “rectification of names”—lies at the heart of Chinese logic. Pre-Qin thinkers regarded the rectification of names as an essential task. Through sustained debates about the relationship between concepts and the things they represent, they explored universal methods for ensuring proper correspondence between concepts and realities, distinguishing things and categorizing them, and clarifying definitions. This gave Chinese logic a distinctly instrumental character as a method of reasoning and argumentation. However, pre-Qin thinkers held divergent views on why names should be rectified and how the process should unfold. Such differences precisely demonstrate the richness of Chinese logical thought as it developed into a unique theoretical system during its formative stage.

As an uninterrupted civilization, China has preserved the continuity of its logical traditions as tools of argumentation across dynasties. After the Qin (221–207 BCE) and Han (202 BCE–220), Chinese logic exhibited distinct characteristics at various stages of philosophical and cultural development. In the context of Confucian classics studies in the Han Dynasty, for example, forms of logical argumentation emerged, centered on the interpretation of canonical texts. In the Wei and Jin era (220–420), the rise of metaphysics emphasized rhetorical refinement and skillful debate, forming a mode of discourse with strong stylistic features of the age. The Song (960–1279) and Ming (1368–1644) dynasties marked a new phase in the evolution of Chinese philosophy and culture. The emergence of a new Confucian ontology in the Northern Song (960–1127) revealed new orientations in Chinese philosophy. As a fundamental method of argumentation, Chinese logic, integrated with the construction of Confucian ontology, displayed new characteristics that advanced its deeper development. During the Ming and Qing (1644–1911) dynasties, China entered a period of social upheaval. After its peak development, Song-Ming Neo-Confucianism was largely unable to meet the practical needs of responding to social change and crisis. The long-suppressed spirit of practicality surged unprecedentedly in the Ming and Qing, giving rise to a trend of empirical and pragmatic scholarship. Practical learning and the principle of humanistic pragmatism flourished. The development of Chinese logical thought in this period correspondingly reflected these broader intellectual and cultural shifts.

Alongside this continuity, Chinese logic also exhibited an openness and inclusiveness characteristic of Chinese culture. With the spread of Buddhism into China, the Indian logical tradition of Hetuvidya was introduced beginning in the Southern Dynasties (420–589) onward. As Buddhism underwent Sinicization, Hetuvidya itself acquired localized features. Both the Chinese-language and Tibetan-language branches eventually became integral components of Chinese intellectual culture.

A medium for cross-cultural exchange

In the modern era, against the backdrop of the “eastward spread of Western learning,” Western traditional logic entered China alongside modern Western knowledge systems. It gradually became the primary methodological tool in research on Chinese logic and helped establish the latter as an independent field of study. Scholarly inquiry into Chinese logic first emerged in Japan during the Meiji period. As Japanese scholars translated and introduced both Western and Chinese learning, they began to apply the theories and methods of Western traditional logic to examine ancient Chinese thought, yielding a series of important insights.

Japanese scholars generally took two opposing positions: Some argued that China lacked logic altogether, as in Matsumoto Bunzaburō’s assertion in 1898 that Chinese philosophy had no study of logic; others insisted that China possessed a rich logical tradition. In 1900, Kuwaki Genyoku authored “An Outline of the Development of Ancient Chinese Logical Thought” and “Xunzi’s Logic,” arguing that Xunzi’s inquiry into concepts was in some respects even more profound than Aristotle’s. These two positions directly influenced modern Chinese academia, and the view that China had its own logical traditions was positively received and developed further. Beyond scholars such as Sun Yirang, Zhang Taiyan, Liu Shipei, Liang Qichao, and Wang Guowei, others also recognized the existence of Chinese logic by examining its relationship with Chinese scholarly traditions. Some argued that the fundamental differences between Western, Indian, and Chinese scholarship arise from the fact that “each system has its own distinctive doctrines of concepts and methods.” As such, understanding Chinese logic is a prerequisite for grasping the broader landscape of Chinese scholarship.

The development of modern Chinese logic vividly reflects the process and mechanisms through which Chinese and Western cultures moved from collision to integration. It also serves as an intermediary linking the two knowledge systems, as logic serves as the foundation of knowledge systems and plays a supporting role. For two disparate knowledge systems to correspond and engage with each other, the connection must begin at this foundational level. Internally, Chinese logic continues the lineage of pre-Qin philosophy and its knowledge structures, extending through the entirety of traditional Chinese philosophy and its knowledge system. Externally, it interfaces with Western logic and extends into modern Western philosophy and its knowledge system, forming an intellectual bridge between the cultures of China and the West.

Unique value to world systems of logic

Since the mid-20th century, international attention to Chinese logic has grown significantly. As the only logical tradition grounded in a non-Indo-European language, Chinese logic has drawn scholarly interest for its distinctive characteristics and its potential contributions to global logical inquiry.

In Joseph Needham’s Science and Civilisation in China’s Volume 7, Part 1: Language and Logic (1998), German sinologist Christoph Harbsmeier pointed out that the history of logic in China—based on a non-Indo-European language—is of special importance to any global history of logic and hence to any global history of the foundations of science. He criticized the view that “logic belongs exclusively to the West,” arguing that Chinese language and grammar contain a sophisticated capacity for logical expression and reflect distinctive modes of logical thinking.

To understand the value of Chinese logic, it is important to situate it within the broader features of world systems of logic. Ancient Greek, ancient Indian, and Chinese logic can be viewed as three fundamental types that developed in parallel within the global logical tradition. Systematic study allows scholars to extract the general qualities of the world’s logical systems. At the same time, Chinese logic—as a component of Chinese culture—requires research into the emergence and development of Chinese logical thought itself, probing the aspects that reflect China’s cultural individuality. Through comparative study and mutual learning with ancient Greek and Indian logic, the unique value of Chinese logic within the world logical systems can be elucidated.

A direct result of China-West cultural exchanges

The transformation of modern Chinese thought was closely intertwined with exchanges and convergences between Chinese and Western cultures. The various intellectual changes and transitions that emerged in Chinese scholarship during this period can, in a sense, be understood as a direct consequence of interactions between the two traditions. In particular, after Western logical theories and methods gained wide acceptance within the Chinese intellectual community, modern scholars began to employ new concepts and methodologies to reassess China’s indigenous traditions. This led to bold theoretical exploration and innovation which spurred the transformation of traditional philosophy and the construction of modern philosophical systems.

The construction of modern Chinese philosophy unfolded across three key levels, each closely connected to developments in modern Chinese logic research and a direct outcome of China-West intellectual exchange. The first was a transformation in conceptual frameworks. After Western culture entered modern China—through social movements and intellectual transformations such as the Self-Strengthening Movement and reformist thought—and alongside a shift from Confucian classics studies to the study of various traditional philosophical schools, most scholars gradually recognized the limitations of traditional thought and scholarship. They increasingly looked beyond China toward Western learning in search of a practical path for China’s future. The spirit of science and the concept of rationality became central to this intellectual shift.

The second level involved the construction of methodology. The building of any philosophical system depends upon methodology, yet traditional scholarly methods could hardly meet the needs of reconstructing entire philosophical systems. Through its introduction and dissemination by scholars like Yan Fu, Western logic was gradually accepted and, within certain circles, adopted as a new methodological tool.

The third level was the construction of systems. In the early 20th century, three major intellectual trends took shape in modern Chinese philosophy: Marxist philosophy in China, modern New Confucianism, and Chinese positivist philosophy. Together, these trends formed the new landscape of Chinese modern thought. Among them, positivist philosophy was most directly linked to Western logic. Western logic was not only introduced to China as a new system of thought, but also, as a new method, began to influence the transformation of modern Chinese scholarship and culture, directly leading to the emergence of new philosophical systems in modern China.

The development of Chinese logic, like the construction of contemporary Chinese culture, stands at the convergence of the ancient and the modern, bridging China and the West. To further advance Chinese logic, it is essential to draw upon the wisdom of China’s traditional culture and philosophy while learning from the achievements of modern logic, thereby contributing to the construction of an independent knowledge system for Chinese philosophy and social sciences.

Li Chunyu is an associate professor from the School of Marxism at China Medical University. Zhai Jincheng is a professor from the College of Philosophy at Nankai University. This article has been edited and excepted from Guangming Daily (April 21, 2025).

Copyright©2023 CSSN All Rights Reserved