Xixia Imperial Tombs epitomizes multiethnic integration

Green-glazed chiwen ridge ornament Photo: Lu Hang/CSST

Gilded bronze ox Photo: Lu Hang/CSST

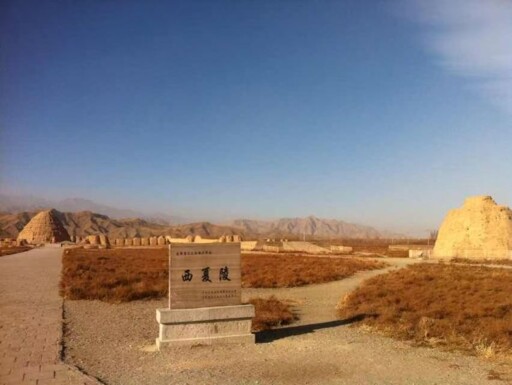

The Xixia Imperial Tombs site Photo: Lu Hang/CSST

On the eastern foothills of the southern Helan Mountains in Yinchuan, Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, vast stretches of the Gobi Desert are dotted with enormous conical mounds. Set against layered mountain ridges, they form a scene of austere grandeur. Since the Xixia Imperial Tombs were inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List, this treasure of Chinese civilization has drawn visitors from all directions. Here, they touch the pulse of history, encounter a world both mysterious and distinctive, and experience the profound appeal of the community for the Chinese nation.

Millennial memories in museum

Entering the archaeological site park of the Xixia Imperial Tombs, visitors find that the raw, earthy tones of gravel allow the thematic museum to blend seamlessly into the surrounding Gobi landscape. Nestled discreetly beside the ruins, it presents itself in an understated, almost “hidden” form. Inside the exhibition halls, a lifelike gilded bronze ox and lustrous green-glazed chiwen (a mythical beast) attest to the superb craftsmanship shared by the Western Xia and Central Plains civilizations. Fragmented steles inscribed in Tangut and Han scripts offer glimpses into the depth of cultural exchange between the Song (960–1279) and Western Xia dynasties. Architectural components such as sutra pillars bear witness to Buddhist beliefs, while funerary artifacts—including coins, silk, and beaded ornaments—serve as material evidence of the Western Xia’s links to the ancient Silk Road.

An exquisite gold head ornament weighing over 200 grams, displayed at the Xixia Imperial Tombs Museum, is decorated with interconnected lotus-petal bead patterns, with one side featuring a kalavinka—a mythical being with a human head and bird body. According to Shi Peiyi, curator of the museum, the interconnected lotus-petal bead motif symbolized auspiciousness in Tang (618–907) and Song culture. The kalavinka, also known as the “wonderful-sounding bird,” appears frequently in Western Xia artifacts, underscoring the profound influence of Buddhism on the dynasty’s history and culture. The harmonious coexistence of Central Plains–style lotus motifs and the kalavinka imagery on this ornament vividly illustrates cultural exchange among China’s various ethnic groups.

The ceramics industry of the Western Xia not only bears the imprint of Han culture from the Central Plains but also reflects the Tangut people’s lifestyle and nomadic traditions, giving rise to distinctive regional characteristics. These artifacts constitute essential material evidence for understanding the material life of the Western Xia period. Zhu Cunshi, chief expert of the National Social Science Fund–sponsored major project on the Helan Suyukou porcelain kiln site and director of the Ningxia Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology (NICRA), explained that Western Xia–period discoveries include finely crafted plain white porcelain produced specifically at the Suyukou kiln site, as well as a substantial quantity of ceramics fired at kilns such as Lingwu Ciyaobao. Some vessels feature carved or incised decorative patterns, among which the most representative form is the flat pot, typically fitted with two or four loops on either side for carrying or suspension. This design is believed to have evolved from leather water pouches used by nomadic peoples, while the ring foot on the vessel’s body ensures stability when placed on a surface.

“The hoof-shaped foot at the base of Western Xia flat pots distinguishes them from similar pots of the Liao (916–1125) and Yuan (1271–1368) dynasties, allowing the vessels to stand steadily,” added Chai Pingping, an associate research fellow at the NICRA.

Distinctive architectural features

Stepping into the Xixia Imperial Tombs site, time seems to pass lightly over broken walls and scattered stones across the Gobi Desert. Each remnant tells a story of cultural fusion. The architectural elements of the mausoleum complex draw together multiple cultural lineages, forming a unique visual language. Across these burial sites, the rise and fall of the Western Xia Dynasty unfold in silent testimony to history’s vicissitudes.

Under the sunlight, nearly a thousand informational plaques are installed throughout the site, displaying ancient Tangut script alongside Chinese characters and English text. Through these specially crafted ceramic panels, the archaeological excavations, spatial layout, heritage value, and cultural significance of the Xixia Imperial Tombs are vividly presented.

The tombs complex contains nine imperial mausoleums, whose surviving remains are composed primarily of rammed earth. Although their individual areas vary, their overall structures and layouts follow a similar pattern. Mausoleums 1 through 6 preserve their layouts and architectural remains most completely, with above-ground features clearly visible. Mausoleum 7 retains roughly half of its above-ground structures, while Mausoleums 8 and 9 are marked mainly by their surviving towers.

Against the vast sky and expansive wilderness, the tower of Mausoleum 3 is the most striking. Its tall watchtowers still convey a sense of majesty despite a millennium of exposure to the elements. The stone statues within the “Moon City,” though damaged, continue to stand guard. Amid the ruins of the sacrificial hall, one can readily imagine the solemn rituals once performed there. The circular mausoleum tower, constructed from rammed earth mixed with gravel, is a rare form among ancient burial complexes. Yang Rui, deputy director of the Xixia Imperial Tombs management office, noted that Mausoleum 3 is believed to be the tomb of Li Yuanhao, the founding emperor of the Western Xia Dynasty. It was the earliest to be opened and remains the best preserved.

Chen Tongbin, honorary director of the Architectural History Research Institute at China Architecture Design and Research Group and head of the consulting team for the site’s World Heritage nomination, observed that the Xixia Imperial Tombs reflect multiethnic and multicultural exchange in their site selection, spatial layout, and burial system. They help corroborate the historical reality that the Song, Liao, Western Xia, and Jin (1115–1234) dynasties of the 11th to 13th centuries all formed part of the Chinese nation, filling important gaps in the historical narrative of the Western Xia.

While scholars have often characterized the Western Xia as merely “inheriting from the Tang and imitating the Song,” Chen noted that it was in fact built upon extensive learning from Central Plains civilization while integrating Tangut customs and beliefs. The Xixia Imperial Tombs demonstrate the Tangut people’s capacity for learning alongside a commitment to innovation, revealing a pattern of multicultural integration forged through sustained interaction and exchange among regions. This constitutes a vital source of the enduring vitality of Chinese civilization and serves as direct evidence of its continuity, innovation, unity, inclusiveness, and peaceful nature.

Traces of multicultural interaction, coexistence

For a variety of reasons, the Western Xia Dynasty has long remained relatively unfamiliar to the general public. In 1908, a Russian expedition discovered the ruins of the Western Xia city of Heishui (in today’s Alxa League, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region) and removed over 3,500 artifacts, which remain preserved overseas. This created an awkward situation in which Western Xia history is part of Chinese history, yet the study of the dynasty largely developed abroad. A decade ago, Western Xia expert Li Fanwen told CSST that the discovery and excavation of the Xixia Imperial Tombs filled many historical gaps and provided an opportunity to anchor Western Xia studies more firmly within China.

Artifacts unearthed from the tombs offer a comprehensive reflection of Western Xia society, encompassing social history, productive capacity, living customs, artistic styles, technological levels, and patterns of trade and exchange. Over successive archaeological surveys and excavations, large quantities of artifacts have been collected from the imperial tombs, associated burial pits, and architectural sites at the northern end of the complex.

At present, in addition to the 7,100 artifacts preserved by exhibition and collection institutions, the site itself still contains numerous fragments of architectural components. These artifacts primarily include building materials and structural elements, fragments of stone steles and other carvings, ceramics, animal-shaped vessels, skeletal remains, horse gear, weapons, coins, clay sculptures, mural fragments, and decorative objects, tools, and daily utensils made from various materials.

Building materials and components are the most numerous, ranging from ordinary bricks and tiles to finely crafted decorative elements such as ridge ornaments, carved dragon columns, chishou (mythical creature heads), and column bases. Pottery predominates, with glazed items accounting for a notable share, followed by specialized materials such as ceramic tiles, while stone and wooden components appear in smaller numbers. Ridge ornaments—represented by chiwen and pinjia (a mythical bird)—along with patterned bricks, tiles, and stone architectural elements, display distinctive forms and refined craftsmanship, reflecting the unique artistic style of the Western Xia.

Situated at a crucial junction of the ancient Silk Road that linked Eastern and Western cultures and facilitated long-distance trade, the Western Xia played a prominent role in sustaining transcontinental exchange along the routes from the 11th to 13th centuries. Du Jianlu, dean of the School of Ethnic Studies and History at Ningxia University, told CSST that the Western Xia made full use of key Silk Road routes, including the Hexi Corridor and the Juyan Route, trading and interacting with neighboring polities such as the Song, Liao, Jin, and Tubo through tributary missions, government-regulated markets, and border trade. Coins, silk fabrics, glass beads, and malachite ornaments unearthed from the tombs attest to these exchanges, revealing the Western Xia’s role as a hub in long-distance, transregional commerce across Eurasia.

Historical records show that Western Xia territory was home not only to the Tangut people but also to Han, Tubo, Uighur, Tatar, Khitan, Jurchen, and other ethnic groups, each with distinct subsistence modes, religious beliefs, and customs. Together, these elements shaped the dynasty’s multicultural character and testify to the Xixia Imperial Tombs as a powerful symbol of the community for the Chinese nation, one characterized by the coexistence of diverse cultures with the Tangut as the dominant group.

Editor:Yu Hui

Copyright©2023 CSSN All Rights Reserved