Agricultural transformation through prism of body and memory

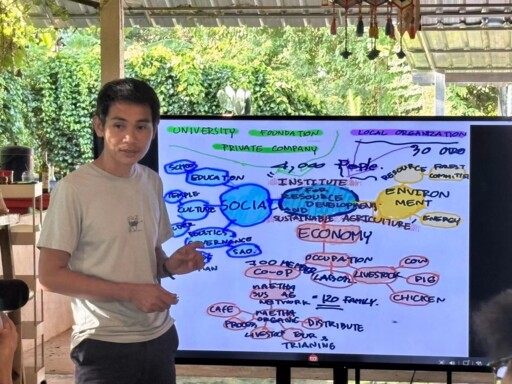

A Mae Tha villager explaining the history and framework of the village’s organic farming system Photo: PROVIDED TO CSST

Since 2019, the School of Ethnology and Sociology at Yunnan University (China) and the Regional Center for Social Science and Sustainable Development at Chiang Mai University (Thailand) have collaborated on short-term field investigations, sending mixed teams of students and jointly led faculty to rural sites across Chiang Mai and Chiang Rai provinces in northern Thailand.

In 2025, the author’s team carried out fieldwork in Mae Tha Village, where a transition toward sustainable and organic agriculture has gathered momentum in recent years and injected new vitality into local farming life. Both older and younger villagers speak with evident attachment to agriculture. Their accounts usually begin with lived experience, framing the village’s agricultural transformation through the intertwined perspectives of the body and memory—a vantage point that differs from mainstream narratives and offers a more textured understanding of how this transformation has taken shape.

In the era of subsistence agriculture, production in Mae Tha relied primarily on oxen plowing and manual labor. Family members supported one another, and the need for hired labor was minimal. In villagers’ recollections of this period, the natural environment and bodily well-being figure prominently—“people did not easily fall ill” because “everything they ate was natural.” These bodily perceptions are shared by both older residents, who recall past experiences directly, and younger villagers, who recount what they learned from parents and elders. Such embodied experiences form the core of Mae Tha’s collective memory. Traditional agriculture is depicted as a holistic socio-ecological system characterized by good health, harmonious family relationships, stable social ties, and a beautiful natural environment. This memory later became a key reference point for critiquing industrial agriculture and advocating for organic farming.

In the 1960s, the Thai government and private companies began to promote monoculture farming practices, requiring villagers to plant cash crops, along with the extensive use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides. Although farmers retained ownership of their land, they no longer had full autonomy over what to grow, how much to grow, or when to grow. “Farmers were like hired laborers” is the main recollection of this period. Heavy reliance on agrochemicals led to declining soil fertility, polluted water sources, and ecological degradation. At the same time, many villagers began experiencing health problems due to pesticide exposure.

To comply with the monoculture directives, many villagers borrowed money to buy seeds, fertilizers, and pesticides. Household debt mounted, yet income often fell short, forcing many families to turn to migrant work, causing family ties to weaken. Because monoculture depends on capital and technological inputs to raise yields, cooperation among farmers diminished while competition intensified, straining relationships within the village. The negative consequences of monoculture became part of villagers’ profound embodied and lived memories.

In the 1980s, a small number of villagers began experimenting with chemical-free and diversified farming, drawing attention and support from non-governmental organizations. In 2000, villagers established the Mae Tha Sustainable Agriculture Cooperative based on family and neighborhood networks. In recent years, young rural returnees, recognizing the potential of organic agriculture, founded the Mae Tha Organic Agriculture Community Enterprise. Beyond selling agricultural products, the enterprise has expanded into tourism, experiential activities, and community cafés, integrating organic farming with consumer culture and the experience economy.

Villagers generally believe that agrochemical use causes illness and physical debility, whereas organic farming “restores their health.” This embodied experience serves as a powerful justification for the shift to organic agriculture. For most villagers, organic farming offers substantial labor autonomy and serves as an important means of rebuilding family and community ties—key reasons why many young returnees choose to engage in organic farming.

For Mae Tha villagers, the narrative of body and memory serves a dual function. On one hand, it provides an experiential logic that guides individual and family decision-making. Values centered on physical health and family cohesion lead them to persist with organic agriculture, even when economic returns remain modest. On the other hand, this narrative constitutes a form of collective social imagination. Through intergenerational transmission and local institutional arrangements, villagers pass these stories to younger generations, sustaining the continuity of organic practices and community life. In this sense, Mae Tha’s agricultural transformation is not only an economic and ecological adjustment—it is also a process in which individual experience, bodily perception, and collective memory underpin social practice and reinforce shared values.

He Haishi is a professor from the School of Ethnology and Sociology at Yunnan University.

Editor:Yu Hui

Copyright©2023 CSSN All Rights Reserved