The enduring legacy of Song culture

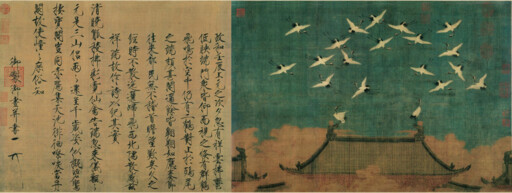

FILE PHOTO: “Auspicious Cranes” by Emperor Huizong, the eighth emperor of the Song Dynasty and the most artistically accomplished of his line, with an inscription in the Slender Gold style, a sophisticated calligraphy style invented by Emperor Huizong

A green-glazed porcelain vase from the Song Dynasty, preserved in the National Museum of China Photo: Ren Guanhong/CSST

Song culture refers to the distinctive cultural system that emerged in China between the 10th and 13th centuries—a period marked by remarkable advances in social institutions, philosophy, literature, the arts, and science and technology. A vital part of Chinese civilization and its refined traditional heritage, this era is recognized as one of the most culturally prosperous in Chinese history. It gave rise to a refined, inclusive, pragmatic, and innovative cultural paradigm that has exerted a profound influence not only on subsequent Chinese society but also on East Asia and world culture at large. Functioning as a pivotal nexus in the evolution of Chinese civilization, Song culture inherited the foundational legacies of the Han (202 BCE–220 CE) and Tang (618–907) dynasties, yet advanced them in transformative ways, laying a solid foundation for the cultural developments of the Yuan (1271–1368), Ming (1368–1644), and Qing (1644–1911) periods.

The eminent modern historian Chen Yinque famously asserted that the culture of the Chinese nation “reached a peak under the Song Dynasty,” underscoring the Song era’s luminous place in the broader tapestry of Chinese civilization. Historian Deng Guangming noted that the material and spiritual civilization achieved during the Song Dynasty reached a remarkable height in the history of China’s feudal era. By the Song period, Chinese civilization had already undergone extensive material and cultural expansion. The establishment of a robust civil bureaucracy, the rise of street commerce, paradigm-shifting developments in Neo-Confucian thought, and a flourishing literary and artistic milieu accessible to both elite and popular audiences all combined to forge a cultural synergy that transcended time and space—forming the enduring charm of Song culture.

Unique political and intellectual ecosystem dominated by scholar-officials

The Song Dynasty marked a pivotal transition in the evolution of China’s political civilization. Renowned translator and writer Yan Fu noted that the Song era is very instructive for the study of changes in human sentiment and political customs. As the last of the so-called “Later Three Dynasties,” alongside the Han and Tang, the Song period embedded political and cultural values deep within the fabric of Chinese society—legacies that persist to this day. The well-developed civil service examination system dismantled rigid social hierarchies, enabled the systematic mobility of literati, and fostered the rise of the scholar-official class. This group played a crucial role in shaping the traditional Chinese model of “governing through culture,” contributing to a unique political and intellectual ecosystem dominated by scholar-officials.

Inspired by the grand ideals of “ordaining conscience for Heaven and Earth, securing life and fortune for the people, continuing the lost teachings of past sages, and establishing peace for all future generations,” scholar-officials fused personal ideals with national commitment. Figures such as Fan Zhongyan—with his famous ethos of “anticipating the worries of the people and being the first to care, and being the last to enjoy, only after seeing that others were all happy”—and Wang Anshi—whose reformist zeal dared to challenge the course of destiny—embodied the values of “self-cultivation, regulation of family affairs, good state governance, and ensuring peace to all under Heaven.” Together, they erected a spiritual monument to the Song intelligentsia and elevated Confucian thought from ethical guidance to a reference for institutional reform. This unique scholar-official political culture not only ushered in a high point in civil governance of China, but also left a lasting legacy of political wisdom and ethical governance.

Flourishing commerce and economy

Historian Qian Mu once argued, “To understand the transformation of Chinese society, one must look to the Song era.” The roots of such transformation lay in the economy. Though some historians labeled the Song Dynasty as one of “accumulated poverty,” this period in fact fostered some of the most revolutionary economic forms in China. The national economic center shifted decisively southward, with the Yangtze River basin supplanting the Yellow River basin as the nation’s new economic heartland.

Commerce greatly flourished. Trade transcended spatial and temporal constraints, with night markets and early morning fairs proliferating, while marketplaces spread throughout rural areas. Urban centers such as Bianjing [present-day Kaifeng, Henan Province] and Lin’an [present-day Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province] boasted populations exceeding one million. The invention of jiaozi, the world’s first paper currency, signaled a new height of the Song’s commodity economy. The bustling marketplace scenes in the painting “Along the River During the Qingming Festival” offer a glimpse into this vibrant economic landscape. This prosperity profoundly shaped the social character of Song culture, spurring a cultural transformation that—while rooted in Han and Tang traditions—moved toward the modern. The growth of a commodity economy and the rise of a civic class brought about a process of cultural secularization, resulting in a unique, vibrant cultural ecosystem that appealed to both elite and common tastes.

‘Golden age’ of technological achievements in ancient China

The Song era represents a “golden age” of scientific and technological achievements in Chinese history, even influencing the trajectory of world civilization. Song scientific culture was systematic, utilitarian, and innovative. It synthesized earlier technological knowledge while radiating its achievements globally via the Maritime Silk Road. As Joseph Needham noted, “Whenever one follows up any specific piece of scientific or technological history in Chinese literature, it is always at the Sung [Wade-Giles transliteration of “Song”] Dynasty that one finds the major focal point.”

The “Four Great Inventions” of ancient China enabled critical advancements during this period: Movable type printing accelerated the dissemination of knowledge; compass technology powered maritime exploration and trade; and the transmission of papermaking and gunpowder feuled world civilizations. Works such as Dream Pool Essays and Complete Essentials for the Military Classics exemplify empirical inquiry and a proto-scientific spirit. Innovations in porcelain production and textile machinery further reflected the ethos of refinement and craftsmanship.

Intellectual landscape marked by harmony in diversity

Historian Wang Guowei wrote that “In terms of intellectual vitality and cultural diversity, the Song surpassed both the Han and Tang, and none after could match it.” In philosophy and scholarship, Song culture reached new heights, with Neo-Confucianism (Lixue) at its core. This intellectual reform of Confucianism stemmed from a critical engagement with Han and Tang classical traditions and a creative response to the challenges posed by Buddhism and Taoism. Thinkers such as Zhou Dunyi and Zhang Zai integrated Taoist cosmology into Confucian thought, introducing concepts like the “Explanation of the Diagram of the Supreme Ultimate” and the “Ontology of Qi,” which laid the foundation for a metaphysical cosmology. The Cheng brothers [Cheng Hao and Cheng Yi], drawing on Chan Buddhism’s discourse on mind and nature, elevated ethical norms to the level of metaphysical “Heavenly Principle” (Tianli). Zhu Xi synthesized diverse schools of thought through his doctrine of “principle is one but its manifestations are many,” constructing a moral epistemology based on the investigation of things to extend knowledge. Meanwhile, Lu Jiuyuan’s proposition that “the mind/heart is principle” laid the groundwork for Wang Yangming’s School of Mind in the Ming Dynasty. This vibrant intellectual landscape—marked by harmony in diversity—nurtured a spirit of inclusivity and rationality that endowed Song culture with enduring vitality.

In the realm of literature and the arts, the Song Dynasty stands out as a bright and influential force in the long history of Chinese civilization. Ouyang Xiu spearheaded literary reform, while Liu Yong popularized ci poetry with lines so beloved they were said to be sung “wherever there was well water.” Su Shi expanded ci into the realm of history with works like “Memories of the Past at Red Cliff,” and Li Qingzhao, with her evocative piece “Seeking and Searching,” gave voice to the emotional and existential lives of women. This merging of elite and popular forms made Song ci a mirror of its age. The rise of drama and vernacular fiction signaled a cultural shift from aristocratic narratives to a burgeoning civic aesthetic.

In the millennia-long history of Chinese civilization, Song culture stands as a remarkable spiritual legacy that bridges the ancient and the modern. With its spirit of inclusiveness, commitment to innovation, pragmatic application, rational engagement, deep national consciousness, as well as its ethos of equality and openness, Song culture occupies a crucial position in Chinese history. The influence of Song culture extended far beyond the bounds of its time, leaving a deep imprint on both the course of world civilization and the trajectory of Chinese history.

Wang Mingqin and Tian Zhiguang are professors from the Research Center for Cultural Heritage Inheritance and Innovation at Henan University.

Editor:Yu Hui

Copyright©2023 CSSN All Rights Reserved