Revitalizing the UN knowledge and practice system

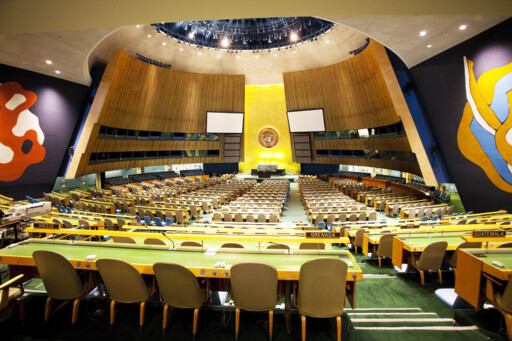

UN General Assembly Hall Photo: TUCHONG

In 2025, the United Nations (UN) will mark its 80th anniversary, a historic milestone in humanity’s relentless pursuit of common governance. Over its 80-year journey, the UN has gradually fostered a rich “knowledge and practice system,” both as the most ambitious crystallization of multilateralist thought in human history and a continuous global governance practice. It has played an irreplaceable and unique role in curbing military conflicts among major countries and maintaining the rare “long peace” in the international community since World War II. However, in the post-Cold War era, the UN’s multilateralist knowledge and practice system has come under unprecedented strain. As global issues grow increasingly complex, the international community faces mounting geopolitical rivalry and disintegrating international order, resulting in both insufficient institutional supply for global governance and a lack of consensus. The long-standing reform of the UN, and of the multilateral global governance system it anchors, has therefore moved beyond technical adjustments, becoming instead a crucial test of whether humanity can achieve self-redemption through rational cooperation.

Systematic crisis of the knowledge and practice system

The UN’s multilateralism mechanism can be regarded as a grand social project in the history of human institutional civilization. It has surpassed countless vague global governance concepts in history, embedding the principle of “great power unanimity” into the framework of collective security and endowing itself with legal authority through the UN Charter. During the Cold War, despite the intense pressures of bipolar confrontation, the UN made indelible contributions in mediating regional conflicts, advancing decolonization, and shaping international human rights norms, with peacekeeping operations even becoming a symbol of “blue hope.”

Today, however, dramatic shifts in the post-Cold War international order expose this framework to the risk of “systemic collapse.” At the ideological level, the spirit of multilateralism is increasingly being hollowed out. Unilateralism and power politics are resurgent, consensus among major powers is scarce, and the Security Council’s veto power is repeatedly abused by Western powers, rendering the collective security mechanism ineffective. At the practical level, global challenges have become far more complex than the system’s designers ever anticipated. Climate change hangs like the sword of Damocles, terrorism spreads in both globalized and fragmented forms, pandemics rapidly cross borders, while the digital divide and artificial intelligence (AI) governance pose new ethical dilemmas. The existing UN agencies, such as the World Health Organization and UNESCO, are struggling with resource constraints, limited mandates, and weak enforcement capabilities, exposing their structural deficiencies in response capabilities. To understand the depth and breadth of the current multilateralism predicament of the UN, it is necessary to examine it from a broader historical cycle perspective. According to “grand cycles” theory, history is often driven by long-term, overlapping cycles that reinforce one another; when multiple key cycles enter decline simultaneously, small troubles converge into systemic crisis. What we face is not a crisis in one domain but the manifestation of an international order unable to withstand the pressures of multiple, layered historical turning points—explaining why global problems are unprecedentedly complex, great-power consensus unprecedentedly rare, and institutional breakdown unprecedentedly prominent.

Some scholars describe the current state of the multilateral system as the UN’s “darkest hour,” with international multilateral cooperation at its lowest point in four decades. At its core, the UN’s deeper legitimacy crisis stems from structural tensions. The General Assembly’s “one state, one vote” principle affirms sovereign equality, yet the Security Council remains frozen in a World War II–era distribution of power that fails to reflect the collective rise of the Global South in decision making. This tension between representational deficit and procedural legitimacy steadily erodes the foundation of the UN’s authority. The multilateral system is thus undergoing a painful transition from being “indispensable” to “overburdened,” from a “symbol of authority” to a “symbol of fragility.”

Rebuilding the community consciousness

Proposals for UN reform put forward by the current international community reveal clashing visions of governance but generally suffer from blind spots in practice, failing to effectively bridge the gap between “knowledge” and “practice.” Certain Western states promote exclusive groupings that divide the international community along value-based lines. Such approaches epistemologically reduce complex civilizational relations to simplistic binaries, methodologically replacing inclusive multilateralism with small blocs, which only risks creating new divides rather than strengthening global governance. Historical experience shows that the vitality of international institutions lies not in the purity of their ideals but in their ability to accommodate diverse interests.

Some states focus on expanding membership in decision-making bodies, though such plans fall into the trap of technical reform. This logic presumes that “more seats mean greater representation,” while overlooking deeper institutional decision mechanism contradictions. Enlarged decision-making increases negotiation costs, while the veto system perpetuates paralysis—reforms may thus weaken effectiveness rather than improve it. The fundamental limitation lies in its failure to address the core issues of institutional design: How to balance sovereign equality with decision-making efficiency. This is fundamentally a problem of “implementation.”

In contrast, the “supranational governance” schemes conceived by the academic community present an idealistic governance vision. However, such schemes face fundamental doubts regarding their implementation paths. Caution is warranted, as institutional designs divorced from real-world foundations are unlikely to take root—in other words, there is a serious disconnect between “knowledge” and “practice.”

Collectively, these reform dilemmas highlight the central contradiction of global governance between knowledge and practice: the need to transcend the limits of the sovereign state system without denying its realities, to respond to the call of a global community of shared future while navigating persistent conflicts among states. Most proposals fail to confront the root cause of the disconnection between knowledge and practice—the structural contradiction between a profoundly changing global power landscape and severely outdated governance mechanisms. Against this backdrop, the international community urgently needs to find a new path that takes into account both ideals and reality. The present impasse reflects the UN’s knowledge-practice framework lagging behind the times. Revitalization requires more than patchwork adjustments or radical alternatives—it calls for deep civilizational dialogue: to consolidate “knowledge” through mutual understanding, to rebuild “practice” through democratic consultation, and to cultivate a sense of a “knowledge-practice” integrated community through joint action.

The Chinese solution

In the face of these challenges, the international community looks to major powers to shoulder constructive responsibility. China, as a consistent supporter and contributor to the UN, has long worked to uphold the purposes and principles of the UN Charter and to support the UN’s central role in global affairs. China’s growing participation and visibility within the UN framework reflect not only its national development but also its response to the pressing question of “what is happening to the world, and what should China do.”

China’s efforts to update and renew the UN-centered multilateral system aim not to overturn or subvert it, but to refine and innovate it—helping the UN and the broader international system overcome current challenges, enhancing their authority, representativeness, and capacity to act, and enabling them to fulfill their sacred mission more effectively. To this end, China seeks to contribute its wisdom, propose constructive ideas, and offer practical approaches to revitalizing the UN’s knowledge-practice system of multilateralism.

At the level of “knowledge,” China offers several conceptual innovations. First, it advances a multilateral governance concept of “harmonious and inclusive good governance.” “Harmony and inclusiveness” is rooted in China’s civilizational tradition of inclusiveness, emphasizing respect for civilizational diversity and resolving differences through equal dialogue. At its core, this approach encourages inclusive consultation in order to transcend confrontational thinking. “Good governance” focuses on improving governance quality, pursuing the organic unity of democratic process, fairness of outcomes, efficiency optimization, and value guidance, providing fresh ideas for resolving global governance dilemmas.

Second, it proposes a new multilateral approach that integrates development and security. By moving away from the traditional “security versus development” dichotomy, it regards development as the cornerstone of security and advocates for addressing the root causes of conflict through common prosperity. Practices such as infrastructure connectivity have shown that economic integration can effectively reduce regional security risks.

Third, it advocates for promoting “coexistence and mutual learning among civilizations.” It emphasizes the interdependence of human destinies, mutual respect, equal dialogue, reciprocal learning and joint progress among different civilizations—transcending the “clash of civilizations” narrative and transforming civilizational differences into valuable resources for deepening cooperation.

At the practical level, China’s approach focuses on several exploration paths: First, it promotes innovation in decision-making mechanisms to balance efficiency and fairness. This could involve exploring reforms to the representation mechanisms of core institutions such as the Security Council, for instance, by piloting flexible, transparent rotating leadership or issue-based leading mechanisms in smaller groups or specific thematic areas. Such reforms would uphold necessary coordination among major countries while enhancing effective participation from emerging markets and developing countries.

Second, it promotes the construction of a multilateral governance framework for technology ethics to address emerging challenges. In response to the governance vacuum and ethical dilemmas brought about by disruptive technologies such as AI, China could actively advocate for and participate in the establishment of multilateral rules and institutions for technology ethics under the UN framework, ensuring that technological development serves the common interests of humanity.

Third, it encourages explorations of new models for fair and reasonable distribution of global governance power. Particularly in the field of international financial governance, China could promote the restructuring of voting rights and quota allocations to better balance the economic contributions, development needs, and representation of member states, laying a more solid foundation of legitimacy for the global governance system.

Zhai Kun is a professor from the School of International Studies at Peking University.

Editor:Yu Hui

Copyright©2023 CSSN All Rights Reserved