How value conflicts impact mental well-being and self-concept?

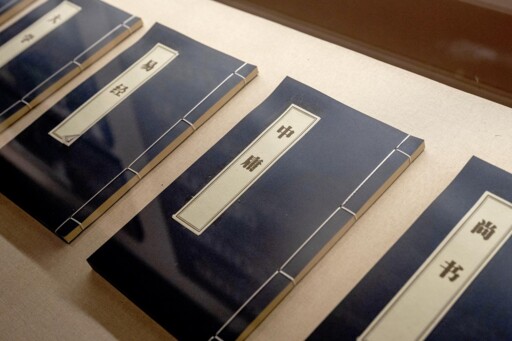

The Confucian principle of the “doctrine of the mean” fosters dialectical thinking and reconciles individual and social orientations, or traditional and modern values. Photo: IC PHOTO

As globalization continues to advance, along with rapid technological development and deepening cultural exchange and integration, people are increasingly confronted with sharp conceptual tensions—between tradition and modernity, East and West, the old and the new. In this context, traditional and conservative values continue to endure, yet they often pose obstacles to the formation of new value systems. At the same time, modern values are gaining vitality amid ongoing social transformation. The friction and competition that arise between individuals who hold differing value systems are referred to as value conflicts.

Undermining sense of well-being

Among Chinese people, one of the most familiar value conflicts is the contradiction between loyalty (zhong) and filial piety (xiao). In modern society, such conflicts have become more diverse in form. For example, traditional values emphasize collectivism, family responsibility, and respect for elders, while modern values focus more on individualism, stressing personal freedom, equality, and rights.

In contemporary psychology, empirical research typically divides value conflict into two major categories: long-term, persistent conflict, and immediate conflict induced in laboratory settings. When individuals are unable to find clear answers in their value choices or fail to reconcile conflicting values over time, value conflict may become a persistent source of distress. Such long-term conflict often leads to ongoing psychological stress and anxiety, gradually undermining their sense of well-being. Given its enduring nature and resistance to resolution, this article classifies it as a long-term conflict and contends that it can exert profound and far-reaching negative effects on individual mental health.

In real life, people frequently face dilemmas similar to the classic tension between loyalty and filial piety in Chinese traditional culture, which demand immediate and definite choices. These conflicts are typically short-lived but intense, requiring individuals to make difficult value decisions under time pressure. Many psychological studies employ value dilemma tasks to simulate such situations and explore the psychological responses individuals exhibit when making snap decisions. Due to their sudden and instantaneous nature, these are categorized as immediate conflicts—characterized by intense, acute internal contradictions and psychological pressure.

Opposing motivations

Many researchers define motivational opposition as the state in which different values are in conflict at the motivational level. Opposing motivations can coexist within an individual’s value system, leading to inner clashes and conflict. This view is grounded in the theory of the circular structure of values developed by Shalom H. Schwartz, a renowned Israeli social psychologist. His model offers a systematic framework for understanding and categorizing basic human values. Schwartz identifies ten basic value types, arranged along a motivational continuum found across cultures. These values stem from three universal human needs: biological needs, social interaction needs, and the need for group survival and well-being.

According to this framework, values are organized into ten basic types. Rather than being independent, these motivational types are either compatible or conflicting, arranged in a circular structure. In this model, adjacent values share similar motivational goals, while opposing values are positioned across from each other. Since these values represent different goals and motivations, conflicts may arise between them. For instance, values emphasizing self-enhancement may conflict with those emphasizing self-transcendence—the former focusing on personal success and dominance, the latter highlighting care for others and promotion of social harmony.

Schwartz’s motivational hypothesis of the value system has received substantial empirical support. Numerous studies have found that identification with and evaluation of values are closely related to individuals’ emotional experiences. Longitudinal research across different age groups has also confirmed the compatibility and incompatibility relationships among values proposed by Schwartz’s model. His framework provides a plausible explanation for the emergence of value conflict: pursuing motivationally opposing values simultaneously is often psychologically untenable.

Cognitive dissonance theory suggests that people have a fundamental need for internal consistency and continuity in their beliefs. When competing or contradictory values coexist, they can disrupt cognitive coherence and completeness. If individuals attempt to integrate opposing values into their own belief system, a state of motivational tension may arise.

However, existing research suggests that motivational opposition alone cannot fully account for the experience or negative consequences of value conflict. For instance, some studies have found that individuals may feel little or no conflict even when endorsing motivationally incompatible values. In contrast, difficulties in choosing between compatible values may also trigger internal conflict—a phenomenon that cannot be explained solely by motivational opposition.

Self-concept consistency

Some researchers argue that the conflict and resulting psychological distress caused by simultaneously activating multiple values stems from a perceived threat to the consistency of one’s self-concept—that is, value conflict originates at the level of self-identity. Psychological and neuroscientific studies on values have shown that values occupy a central position in individuals’ self-identity and self-perception. Clashes between values often trigger processes of self-involvement, as values that are more important to an individual tend to be more tightly integrated with their self-concept.

Therefore, conflicts and tensions between values often implicate the self, as making a choice between them frequently entails a decision about which aspect of one’s self-identity to embrace. For example, in a conflict between benevolence and integrity, a judge who wants to show compassion toward the vulnerable may find it difficult to maintain strict fairness—thereby facing a tension between helping others and upholding justice as aspects of self-concept.

Existing research on self-concept has found that individuals have a fundamental need to maintain coherence and integrity within their self-identity. According to self-discrepancy theory, when individuals hold conflicting or incompatible self-concepts, they may experience psychological discomfort or distress. On this basis, many scholars believe that the perception of a threat to self-concept consistency—when individuals are forced to choose between competing values—is the psychological root of value conflict and its associated negative effects.

A number of experimental studies based on value-related dilemmas have provided substantial support for the above theoretical assumptions. When participants are asked to make difficult choices between values they personally prioritize, significant activation is observed in brain regions associated with the default mode network. Moreover, individuals who have experienced more frequent value conflicts tend to show stronger activity in the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, insula, and amygdala. This may indicate that the close link between personal values and self-concept leads participants to experience uncertainty about their identity when facing value dilemmas or wavering in their choices. This identity-related uncertainty may, in turn, trigger stronger emotional responses, potentially marking the starting point of a series of negative psychological outcomes.

If individuals are less likely to perceive threats to the consistency of their self-concept during the process of value contradiction and competition, the level of psychological conflict they experience should correspondingly decrease. Recent empirical studies indeed lend support to this hypothesis, further validating the idea that value conflict stems from perceived threats to self-concept consistency. For example, studies have shown that when participants face value dilemmas arising from conflicting identities, such as tensions between campus life and family obligations, only those who view their self-concept as fixed and stable experience declines in well-being and self-esteem. In contrast, individuals who adopt a more flexible and multifaceted view of the self—known as a dialectical self—are less affected by value conflict.

Further research has indicated that simultaneously endorsing materialistic and environmental values can increase psychological stress and reduce life satisfaction. These negative effects are mediated by self-concept clarity and moderated by individuals’ preferences for self-consistency. In other words, the less concerned individuals are with maintaining a consistent self-concept, the less psychological harm value conflict tends to cause.

Similarly, a 2022 study involving Chinese university students found that some individuals scored highly on conflicting value dimensions but did not exhibit significant signs of value conflict. To explain this, researchers pointed to the Confucian principle of the “doctrine of the mean,” which fosters dialectical thinking among Chinese participants. This mode of thinking allows them to reconcile individual and social orientations, or traditional and modern values, without experiencing internal conflict. This aligns with previous findings suggesting that East Asians tend to hold a more fluid and context-dependent view of the self across different situations.

In summary, two main perspectives currently seek to explain why competing and hierarchically ordered values can give rise to inner conflict and adverse psychological outcomes. The first focuses on the inherent motivational structure behind values, suggesting that conflicts arise because the motivations represented by different values are fundamentally opposed. The second emphasizes the close relationship between values and self-concept, proposing that the psychological distress triggered by value conflict is largely due to perceived threats to the consistency of one’s self-concept.

Based on existing research, the self-concept consistency framework appears to offer a more comprehensive explanation, as it helps account for limitations in the motivational opposition model. However, this does not imply that the two perspectives are mutually exclusive. In fact, values possess both affective-motivational properties and a strong connection to one’s self-concept. Therefore, many value conflicts simultaneously involve motivational opposition and negative emotional responses rooted in efforts to preserve a coherent and integrated self-concept.

Yue Tong is an associate professor from the Faculty of Psychology at Southwest University.

Editor:Yu Hui

Copyright©2023 CSSN All Rights Reserved