End of ‘prophecy’ and China’s search for autonomous sociology

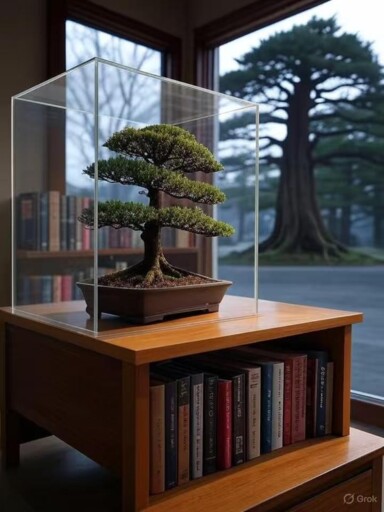

The end of “prophecy” has led to unintended consequences, including the “bonsaification” of research scale—confining scholarly vision to narrow, predetermined domains and lacking both the capacity and the boldness to engage with deeper structural forces and macro-level processes. Image generated by AI

Over the past two decades, disenchantment with social theory—particularly in its “meta-analytical” dimension—has emerged as a notable trend in contemporary Western sociology. Here, “meta-analysis” refers to the effort to integrate a large body of social science evidence into a relatively coherent explanatory framework that can support a set of analytical propositions, thereby revealing—or even predicting—the overall processes and trends of global transformation in technology, economy, society, culture, and politics at the macro level. Although sociology still remains a discipline that values “theorization” and is even driven by theory, it has, almost imperceptibly, distanced itself from this particular mode of theory production and writing.

End of ‘prophecy’ in sociological theory

The so-called “failure” of social theory refers to the collapse of its inherent impulse to portray epochal transformations through grand narratives and to demarcate new eras with striking, slogan-like concepts. Nearly every major contemporary theorist has proposed a signature concept announcing the imminent arrival—or the established reality—of a new age. Yet this impulse has produced a paradox.

On one hand, social theorists still occupy an almost overarching position in the symbolic power structure of Western sociology. Virtually every standard textbook or introduction in sociology reads like a roll call of classic figures such as Marx, Weber, Durkheim, Simmel, and T?nnies, while contemporary “big names” such as Bourdieu, Giddens, Habermas, Foucault, Elias, Baudrillard, Bauman, and Castells are widely recognized as celebrity-level public intellectuals, serving as sociology’s iconic faces to the outside world. Concepts like “risk society,” “post-industrial society,” “consumer society,” and “liquid modernity” have become basic schemata through which people interpret the contemporary world. In this sense, theory hardly appears bankrupt.

On the other hand, among the younger generation of Western sociologists, it has indeed become rare to see new versions of “epochal prophecy” being proposed. Few younger scholars identify themselves as pure social theorists; most are deeply engaged in one or two specialized domains of sociology, pursuing empirical research within those subfields. “Doing theory”—especially in the form of “grand theory” characterized by structural, systemic, and synthetic interpretations of modern society—is no longer the mainstream career path. While most continue to offer ritual citations to the big-name theorists, these references function largely as a vague backdrop, without any ambition or aspiration to “take their place.” In other words, the so-called “failure” of social theory essentially denotes the decline of a writing paradigm marked by “epochal prophecy”—the end of prophecy itself.

Why it happens

Why did prophecy come to an end? One reason is that the endless stream of new theories claiming to define successive epochs has generated a sense of aesthetic fatigue, even disorientation. In this sense, the urge to bestow new name upon the age may have reflected less a genuine analytical necessity than a psychological “anxiety of influence,” spurring theorists into a competition of conceptual invention in order to stamp their analysis of contemporary society with a distinctive imprint.

Another reason lies in the dualistic orientation inherent in prophecy, which rigidly divides past from present. This dualism was a defining feature of sociology at its birth in the mid-19th century. At that time—when sociology was a fledgling discipline striving for legitimacy and identity—prophecies about the arrival of a new age expressed sociology’s very raison d’être: a new discipline responding to a new age, claiming as its mission the diagnosis and management of new problems.

For today’s sociologists, however, such simplified dichotomies of historical time are more likely to obscure the complexity of historical processes. The richness and multivalence of social processes become subsumed under a narrow linear narrative that invariably culminates in some teleological prophecy about the future. Within such a narrative, the detailed examination of present experience no longer matters; what matters is how the present can be fitted into the teleological “package,” regardless of how ill-suited the tailoring may be. Precisely because younger sociologists are trained with an increasingly empirical orientation, this mode of theory has gradually declined.

Professional ‘retreat’ among sociologists

The end of prophecy has also entailed the neglect and weakening of the overarching perspective and historical consciousness that were intrinsic to prophetic writing. This has produced a series of unintended consequences, the most significant of which include the “bonsaification” of research scale, the rise of epistemological “presentism,” and the “de-structuring” of problem consciousness.

“Bonsaification” refers to the confinement of scholarly vision within narrow, predetermined domains, lacking both the capacity and the boldness to engage with deeper structural forces and macro-level processes. The result is a series of fragmented, finely detailed empirical studies that lack an integrated grasp of the structures, contours, and dynamics of contemporary society. Such small-scale studies resemble miniature bonsai enclosed in glass cases—exquisite in form, but offering little insight into society as a whole.

“Presentism,” in British sociologist Fred Inglis’ formulation, denotes the tendency in particular modes of analysis to privilege the concerns and inclinations of the present, often inadvertently and imperceptibly. While Inglis’ critique rightly acknowledges the simplifications inherent in prophetic social theory, particularly its dualistic assumptions, this does not mean we can simply abandon attempts to understand the complexities of long-term historical dynamics and macro-structural transformations. Returning to the present should not mean discarding both past and future. The end of prophecy should not entail the end of inquiry into the mechanisms driving social evolution.

In contemporary Western sociology—where meta-analysis has waned and prophecy has been banished—dominant trends include behaviorist theories grounded in specific contexts and data, and micro-level theories focused on texts, discourse, and the body. Discussions of individual behavior, micro-situations, identity politics, and subject formation have overshadowed concern with social and historical structures, resulting in the “de-structuring” of problem consciousness. Although sociology remains, in essence, a discipline centered on the concept of social structure, in current practice an orientation toward comprehensive questions of social-historical structure has come to seem unwieldy, rigid, and “grand but ineffectual,” and is increasingly marginalized.

These unintended consequences fundamentally signify a kind of “professional retreat” among sociologists. When sociologists cease to inquire into the broad trends of social life, lose sensitivity to the trajectories of historical and structural transformation, and abandon sustained concern for the mechanisms driving the great upheavals of our time—while instead immersing themselves in minutiae, constrained by the strictures of specialization yet proclaiming fidelity to everyday experience and empirical rigor—then such empiricism and normativism amount merely to a regressive, conservative form of empiricism and normativism: an intramural game of knowledge production within academia.

Moving beyond Western scholarship

Much of this discussion has unfolded within the discursive context of contemporary Western sociology. Yet, if we shift the lens to knowledge production within Chinese sociology, we find that the discipline’s historical origins, academic positioning, and contemporary development—as well as Chinese sociologists’ reflections and imaginations on the very possibility and purpose of sociology—differ markedly from the Western experience. As a result, the paradigm of “prophetic sociology” in theoretical writing has not been marginalized in China to the same extent as it has in the West, but instead faces a more complex situation.

To begin with, sociology, and the social sciences more broadly, was imported into China at the turn of the 19th to 20th century, at a moment of rupture in traditional Chinese society. This profound sense of rupture constituted the foundational “structure of feeling” for early Chinese sociologists as they confronted modernity. In the past decade, as development sociology has gradually declined within Chinese academia, research that directly engages with and interrogates transformations of the overall social structure has become rare. Although some works have explicitly declared the arrival of a “new society,” they remain isolated cases, not a sustained trend. In fact, observations and analyses of the structural transformations of society have not received sufficient attention in the current knowledge production within Chinese sociology.

Furthermore, in the practice of empirical research and social analysis, Chinese sociology has long maintained a valuable tradition: It has not been constrained by the dualism intrinsic to “prophetic sociology,” nor has it simply severed ties between past and present. On the contrary, it has historically emphasized and recognized the deep continuities within history. Yet this very tradition of valuing the connections between past and present is itself gradually fading in contemporary Chinese sociological knowledge production.

In any case, China’s position as a “latecomer” in sociology does not necessarily entail imitation or mere following of the West. On the contrary, what we must do is to take the contemporary predicaments of Western sociology as a mirror, while deeply grounding ourselves in China’s own social history and civilizational context, to pursue social research and theoretical work rooted in Chinese realities and experiences. This requires vigilance against the “bonsai effect” of narrowing research scales, the epistemological tendency toward “presentism,” and the erosion of structured problem awareness. At the same time, it demands the adoption of a comprehensive vision and historical consciousness to reflect on the processes and lived experiences of Chinese modernization, thereby constructing a self-conscious and autonomous social theory that truly belongs to China.

Wen Xiang is an associate professor from the School of Sociology at Renmin University of China.

Editor:Yu Hui

Copyright©2023 CSSN All Rights Reserved