Seeking ways forward for humanities and social sciences amid challenges

A striking sculpture from miHoYo Network Technology at “Neo World,” a large-scale metaverse-themed block in Shanghai, a new attempt by the digital creative industry to boost cultural consumption Photo: IC PHOTO

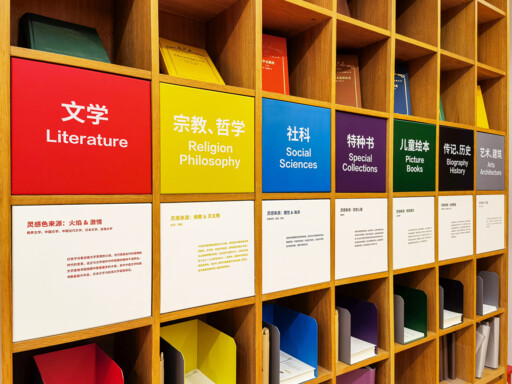

A full spectrum of knowledge: The liberal arts are known for their role in fostering critical thinking, creativity, empathy, and effective communication across diverse cultures. Photo: IC PHOTO

Technology is reshaping the world at a breathtaking pace, with new industries constantly emerging and driving societal demand for professionals with specialized expertise. Against this backdrop, higher education is undergoing profound transformations. Competition among academic disciplines is growing increasingly intense, and resources are gradually being directed toward those fields considered to possess greater “practical value” and “economic benefits.” The humanities and social sciences—disciplines entrusted with the vital mission of preserving and developing human thought, culture, and values—are now confronting unprecedented challenges. For centuries, they have played an irreplaceable role in cultivating critical thinking, creativity, empathy, and cross-cultural communication skills. Yet under the influence of real-world pressures and pragmatic perspectives, these disciplines have run into significant headwinds. In this context, CSST spoke with Melissa Terras, a professor of digital cultural heritage at the University of Edinburgh in the UK, about the challenges facing the humanities and social sciences.

Budget cuts and conceptual challenges

Higher education institutions are grappling with severe funding cuts. Leiden University in the Netherlands is further reducing its course offerings, including psychology programs. Meanwhile, in pursuit of greater economic benefits, the New Zealand government has excluded the humanities and social sciences from the Marsden Fund, a basic scientific research fund, shifting more support toward STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) disciplines. According to data from the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the number of undergraduate degrees awarded in the humanities nationwide decreased by 24% between 2012 and 2022. “There are redundancies happening in the humanities and social sciences across the UK, and Europe, and the US. There are fewer job hires. There are also falling student numbers, given there are fewer courses,” Terras said.

According to Terras, universities in the UK are experiencing a funding squeeze. Larger course sizes are therefore preferred, as they can achieve economies of scale more easily. Many humanities degrees are specialized, and specialized degrees tend do attract smaller cohorts—making them easier to cut, despite being relatively inexpensive to teach compared with the sciences. In some countries, she noted, cuts to the humanities are politically motivated: Authorities may wish to discourage critical thinking or to promote a narrow STEM-focused narrative of innovation, when in reality society needs the critical thinking fostered by the arts and humanities. Human culture and creativity, she emphasized, are essential for addressing the social and political “mess” that afflicts the planet. The skillsets nurtured by the arts and humanities, in other words, are more necessary than ever.

“I think for the most part these pressures are external—years of people being told that humanities degrees are ‘Mickey Mouse,’ cutting of funding to said degrees, pressure for parents not to take ‘Mickey Mouse’ degrees, unavailability of loans and finance to complete these degrees. It’s therefore harder to do these degrees, but falling numbers are pointed to as disciplinary decay. There are plenty of people who want to take these courses,” Terras explained.

“There’s been a huge shift in my lifetime about the understood benefit of going to university. 35 years ago, the rhetoric was that universities were a place for you to develop skills, develop as a person, grow up, develop critically, etc. The ‘getting a job’ focus was the next step, after you had done that. There’s something very sad about thinking of higher education as just the thing you have to do to get a job. It should be more than that—and it is more than that,” Terras continued.

Adding employment value by interdisciplinary integration

One primary obstacle for the humanities and social sciences stems from the view that “liberal arts degrees are useless.” Some universities are attempting to address this pressure by aligning their curriculum with the qualities and skills needed for students’ future careers. The University of Arizona in the US, for instance, has integrated the humanities and social sciences courses with programs in business, engineering, medicine, and other fields, while also training faculty to recruit students with the promise that education in the humanities and social sciences will provide a solid foundation for their future careers.

Central Michigan University in the US is following in the footsteps of the University of Arizona by launching a bachelor’s degree program in “Public and Applied Liberal Arts.” This newly established degree program creatively integrates the humanities and social sciences courses with “applied fields” such as entrepreneurship and environmental studies, with plans to incorporate elements of fashion and game design in the future. Such a design takes into account students’ needs to secure sustainable livelihoods after graduation.

In order to showcase the practical value of the humanities and social sciences, some universities have adopted another strategy: highlighting the remarkable achievements of their alumni in these fields. Several institutions have featured carefully curated success stories on their official websites, while others have produced testimonial videos featuring distinguished graduates—from corporate executives and astronauts to diplomats and celebrated actors.

Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in the US has also introduced an executive education program centered on the humanities and social sciences. In its first two years, the program attracted participants from renowned companies such as Amazon, Microsoft, and Boeing. Students engaged in in-depth studies of history, philosophy, religious studies, classical literature, and the arts, applying insights from these disciplines to examine key issues and qualities of leadership. They also explored how to integrate their learning into emerging technological trends, including cutting-edge fields like data privacy and artificial intelligence. Washington University in St. Louis has similarly sought to break down disciplinary boundaries by, for example, offering French courses for medical students. This program specifically recruits students who studied French in high school but may not have pursued it further. For some students, this initiative led to extraordinary journeys, including advanced study in Nice, France, and internships at local hospitals.

“It depends how you count things! In the UK, the creative industries—all filled with the arts and humanities graduates—are the second biggest industrial sector, bringing in 128bn a year into the UK economy, and bigger than aerospace, automotive manufacturing, and the construction industry. People tend to think graduates from the arts and humanities do not make an economic contribution but this could not be further from the truth,” Terras explained.

“We need to start communicating the economic benefit of the creative industries to the world economy, in a clearer way,” Terras concluded.

Editor:Yu Hui

Copyright©2023 CSSN All Rights Reserved