New Youth: a magazine awakened an era and inspired a nation

The site of the editorial office of New Youth Photo: Duan Danjie/CSST

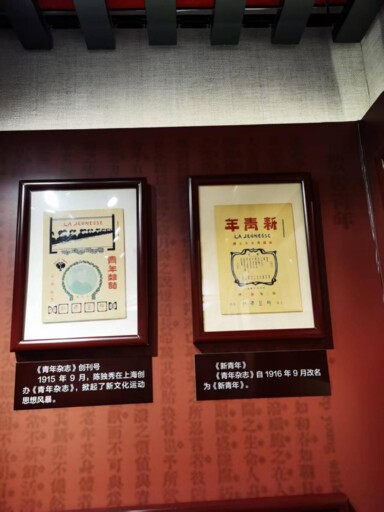

The covers of Youth Magazine (left) and New Youth (right) Photo: Duan Danjie/CSST

A corner of the courtyard Photo: Duan Danjie/CSST

On Sept. 15, the 110th anniversary of Xin Qingnian (New Youth), CSST traced history back to No. 20 Jiangan Hutong, Beichizi Main Street, Beijing (formerly No. 9). Within these walls once stood the magazine’s editorial office and the home of its founder, Chen Duxiu.

Heralding the arrival of a new era

Stepping into the old editorial office, a bamboo table and several bamboo chairs remain in the courtyard. Portraits of Chen Duxiu, Li Dazhao, Hu Shi, and others are etched on the walls, depicting them spirited and impassioned, as if engaged in passionate debate over an important article.

In the early 20th century, China was shrouded in gloom and turmoil. On Sept. 15, 1915, guided by the conviction that “to make the republic worthy of its name, we must first transform people’s thinking,” Chen Duxiu founded Youth Magazine in Shanghai. Beginning with Volume 2, Issue 1, it was renamed New Youth. In 1917, after Chen was appointed dean of humanities at Peking University, the editorial office moved from Shanghai to Beijing, changing from Chen’s sole editorship to a collective publication with an editorial committee.

As the most influential journal of the New Culture Movement and the May Fourth Movement, New Youth struck like a sharp blade at the heart of old ideas. In his inaugural statement “A Call to Youth,” Chen Duxiu declared: “Youth is like early spring, like the rising sun, like budding flowers, like a keen blade freshly honed.”

Bai Ye, a research fellow at the Institute of Literature, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, noted that New Youth championed the new ideas of democracy and science, launched the New Culture Movement, and disseminated the theory and practice of Marxism-Leninism. It became the most powerful platform in modern China for spreading new culture and new ideas, and for opposing imperialism and feudalism. It marked the debut of new thought, heralded the coming of a new era, and ignited the flame of national spirit.

Hu Jun, director of the Li Dazhao Research Center at Peking University, emphasized that the combination of New Youth and Peking University greatly amplified the magazine’s influence. Together, the magazine and the university united academic authority with intellectual vanguardism, breaking through the geographical and “social circle” limits of the author base. It assembled the most substantial intellectual authorship—primarily composed of Peking University professors—thoroughly revolutionizing both the content and combative strength of New Youth. Peking University students became the most ardent readers and most active disseminators of new ideas, achieving a synthesis of intellectual enlightenment and educational practice that laid the intellectual and organizational groundwork for the May Fourth Movement.

New Youth became the stage for the most forward-looking ideas of its time. Hu Shi’s “A Preliminary Discussion of Literary Reform” signaled the start of the Vernacular Movement, bringing culture down from the ivory tower of elites to the people. Lu Xun’s “Diary of a Madman” exposed the “cannibalistic” nature of feudal ethics. Li Dazhao was the first to raise the banner of Marxism in China, proclaiming, “Look at the future of the world, it will surely be a world of red flags!” With fearless critique, its banner of science and democracy, and its open and inclusive stance, New Youth quickly became the heart of the New Culture Movement, attracting countless young seekers of truth.

According to Zhang Guanghai, an associate professor from the School of Literature at Zhejiang University, the magazine left an enduring legacy: a scientific mode of thought and spirit of rational inquiry, a sense of independence and egalitarian democratic concepts, a fresh vernacular style suited to modern society, and a critique of feudal morality. Rather than focusing only on political power struggles, it turned its gaze to culture, ideas, and modes of thinking. It addressed the public, striving to fundamentally reshape the national character at its roots and spread Marxist thought, catalyzing the modern transformation of traditional Chinese culture.

New Youth was a spark that set a prairie ablaze. The generation it inspired and nurtured directly joined the great patriotic May Fourth Movement and ultimately embraced Marxism, laying a solid intellectual and cadre foundation for the founding of the Communist Party of China (CPC).

Pioneering new Chinese literature

New Youth and the New Culture Movement advocated democracy and science while opposing autocracy, ignorance, and superstition. They vigorously promoted new morality against old morality, and new literature against old literature, setting off a wave of intellectual emancipation in Chinese society. Among these efforts, the Vernacular Movement proved the most influential.

In January 1917, Hu Shi published “A Preliminary Discussion of Literary Reform” in New Youth, proposing eight suggestions for literary improvement. Chen Duxiu quickly responded with “On Literary Revolution,” putting forward the “Three Great Principles” of the “literary revolutionary army.” Responding enthusiastically, Qian Xuantong and Liu Bannong staged a “double act” of debate to amplify the influence of new literature. Lu Xun published his vernacular works such as “Diary of a Madman,” “Medicine,” and “Hometown,” pioneering modern literary creation.

Liu Yong, president of the Chinese Modern Literature Association and a professor from the School of Chinese Language and Literature at Beijing Normal University, noted that New Youth gathered the voices of all the leading figures of the May Fourth new literature generation, encompassing nearly every aesthetic form and intellectual resource in the development of modern literature. Adopting the stance of building a new literature—literature for the people—it forged both the discursive strategies and forms of modern literary construction. Its influence among young people was substantial—evidence can be found in the works of Ba Jin, Qian Mu, Feng Youlan, Shen Congwen, Fu Sinian, Luo Jialun, Xia Yan, and others. Bin Jin’s Family, for instance, mentions New Youth 16 times.

The early main arena for Marxist advocacy

After Chen Duxiu and Li Dazhao embraced Marxism, New Youth gradually shifted from cultural enlightenment to Marxist advocacy, even launching special Marxist issues. In his article “My View of Marxism,” Li Dazhao provided the first comprehensive and systematic introduction to Marxist historical materialism, political economy, and scientific socialism, marking the beginning of systematic Marxist dissemination in China.

As the most powerful arena for exploring new ideas, spreading new theories, and preparing for new organizations, New Youth systematically translated, introduced, and spread classical Marxist theory, providing theoretical support for China’s revolution from the perspectives of historical materialism and scientific socialism. Tu Liangchuan, a professor from the School of Marxism at South China Normal University, noted that the magazine engaged in debates with anarchism and reformism, purifying the intellectual environment, highlighting the truth and revolutionary nature of Marxism, and laying a solid ideological foundation for the founding of the CPC. New Youth not only spread ideas but also shaped people. Under its influence, a large number of progressive youth and intellectuals transformed from democrats into Marxists and actively took part in party building—shaking the very foundations of traditional ethics. It thus formed a virtuous cycle linking “theory” and “practice,” achieving an organic leap from theoretical dissemination to the creation of a political party.

In June 1923, after the CPC’s Third National Congress, New Youth became a quarterly publication and served as the first theoretical journal of the CPC Central Committee, contributing to the construction of the Party and to the rise of the Great Revolution. The quarterly New Youth was under the chief editorship of Qu Qiubai, who had just returned from abroad. In the inaugural issue’s “A New Manifesto for New Youth,” he wrote: “The mission of New Youth is to provide correct guidance for Chinese social thought, to provide intellectual weapons for the Chinese laboring common people. New Youth must inevitably become the compass of the Chinese proletarian revolution.” He further proposed that New Youth “should be a journal of social sciences,” “should study the actual political and economic conditions of China,” “should reveal the origins of social thought and arouse revolutionary sentiments,” “should broaden the worldviews of Chinese society and comprehensively analyze world social phenomena,” and “should debate with various schools of social thought for the truth of social transformation.”

Huang Qiaosheng, former executive deputy curator of the Beijing Lu Xun Museum and executive vice president of the Chinese Lu Xun Research Association, explained that after moving from Beijing to Shanghai, the magazine entered a period of concentrated translation and study of Marxist works, publishing the “New Youth Series,” which included Marxist classics such as A History of Socialism and The Class Struggle—which played a vital role in the Party’s theoretical development and inspired successive generations of young people to join.

New Youth was the earliest main front for Marxist advocacy, Hu Jun added. From Li Dazhao’s “My View of Marxism,” to its role as the primary platform for early communist intellectuals, and later its development into the Party’s theoretical journal, it transitioned from intellectual enlightenment to the choice of path.

New Youth exerted immense influence and appeal on progressive youth, awakening a generation of Chinese young people who joined the fervent New Culture Movement. At the former editorial office site, one can still read the six hopes Chen Duxiu expressed for youth in “A Call to Youth”: “Be independent, not servile;” “Be progressive, not conservative;” “Be ambitious, not apathetic;” “Be cosmopolitan, not isolationist;” “Be practical, not formalistic;” “Be scientific, not imaginative.” Today, commemorating the 110th anniversary of New Youth not merely aimed to reflect on history but also to inspire the future—considering how, under new historical conditions, we can better cultivate a new generation capable of carrying forward national rejuvenation.

Editor:Yu Hui

Copyright©2023 CSSN All Rights Reserved