Tracing poetic beauty of Chinese culture

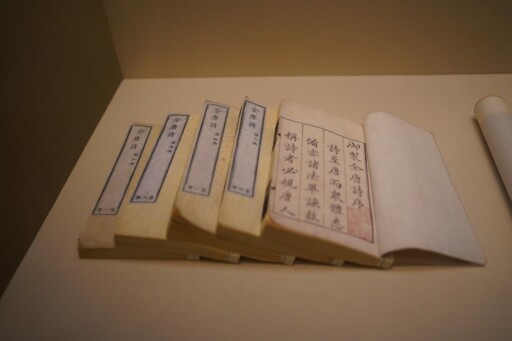

Part of The Complete Collection of Tang Period Poems displayed at the National Museum of China in Beijing Photo: Yang Lanlan/CSST

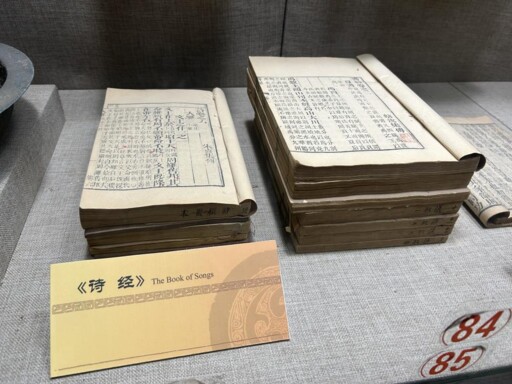

Shijing (The Book of Songs) displayed at the Imperial College in Beijing Photo: Yang Lanlan/CSST

Wenzhang huaguo (refined writing glorifies the nation) is a phrase that has captured the defining cultural tradition of the Chinese people since ancient times. Classical Chinese literature constitutes one of the most vital components of traditional Chinese culture, embodying the profound and vivid spirit of Chinese aesthetics. Among its many literary forms, poetry stands foremost as the genre that most distinctly reflects the aesthetic ideals of the Chinese nation. From Shijing (The Book of Songs) and Chuci (The Songs of Chu), to Tang (618–907) poems and Song (960–1279) ci (lyrics featuring lines of varying length), and further to sanqu (a type of verse drawn from folk music) of the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1911) dynasties, the 3,000-year history of classical Chinese poetry flows like a mighty, ceaseless river of literature. By observing this vast and magnificent current, one can truly perceive the poetic beauty that runs through the essence of Chinese culture.

The beauty of rhythm

The poems in Shijing are primarily four-character lines, most often following a 2–2 rhythmic pattern. By the Han Dynasty (202 BCE–220), five-character and seven-character lines had begun to appear. The five-character line, although only one character longer, adopts a three-beat structure—typically 2–2–1 or 2–1–2—allowing greater flexibility in rhythm. The seven-character lines, composed of four beats, expand semantic capacity and further diversify sentence patterns. Thus, the five-character and seven-character forms gradually became the dominant structures of ancient poetry and remain in use to this day.

A major distinctive feature of classical Chinese poetry is its tonal patterns—the interplay of ping (level) and ze (oblique) tones. Ancient scholars classified the four tones of Chinese phonology into these two categories, reducing the tonal system to a binary contrast: non-level is oblique, and non-oblique is level. This binary allowed poets to alternately weave the two tonal types within a poem, creating resonant and melodious sound patterns.

Exploring these tonal principles was a long and arduous process. In the “Nineteen Ancient Poems” of the late Han period, few verses achieved full tonal harmony. By the Southern Dynasties (420–589), poets such as Shen Yue began to articulate the theoretical basis for tonal regulation. By the late Southern Dynasties, some poets were able to write five-character poems that basically adhered to these standards. By the Tang Dynasty, the system of regulated verse in Chinese poetry was largely established. Early Tang poets had already mastered the art of antithesis, while heyday Tang poets such as Du Fu and late Tang poets such as Li Shangyin pushed it to new heights—transforming it from a formal requirement into a refined artistic pursuit. The integration of line patterns, tonal structures, and antithesis ultimately produced the rhythmic elegance characteristic of five- and seven-character poetry.

Ci poetry represents another major form of classical verse. It emerged alongside court “banquet music” of the Sui (581–618) and Tang periods, roughly taking shape in the Tang Dynasty. Prior to the Sui Dynasty, the court’s ritual music was dignified, slow, and relatively monotonous. New banquet music, by contrast, featured varied and intricate melodies that the symmetrical five- and seven-character lines could not match. Ci, with lines of irregular length—hence the name “long and short lines”—was better suited to these musical forms. Because most ci adopt mixed meters, their tonal patterns are more fluid, lending them particular strength in expressing subtle and delicate emotions.

The beauty of imagery

Classical Chinese poetry privileges imagery over realism in its techniques. What artists valued most was not reproducing the appearance and posture of the external world (including nature and society) but rather expressing the thoughts and emotions of the inner world. For instance, landscape and pastoral poetry could have easily been written as narrative or descriptive works. Yet in the hands of the most celebrated Tang landscape and pastoral poets, such as Wang Wei and Meng Haoran, scenes are often softened and etherealized through lyricism. The mountains, waters, and fields in their poems are depicted as outward manifestations of a tranquil mind and a life of serene detachment. Thus, the ultimate artistic pursuit of ancient Chinese literature and art lies in the vivid creation of subjective imagery.

The ancient Chinese revered the practice of observing things to derive images and expressing meaning through symbols, excelling at grasping abstract truths through concrete forms. The hexagrams in Zhouyi (The Book of Changes) and the pictographic nature of Chinese characters both embody this mode of thought. The ancients long recognized that the Dao—the underlying order of things—is subtle and difficult to articulate. Confucius often employed poetic language to express philosophical insight: “Only when the year turns deadly cold do we see that pines and cypresses are the last to wither.” Daoist writings go even further—Zhuangzi, for instance, reads like poetry throughout, its philosophy of life both profound and accessible through rich and evocative imagery.

Because poetic thought is intuitive rather than analytical—its language ambiguous and polysemous rather than clear and singular and its meaning always extending beyond its words rather than being exhausted by them—poetry becomes the ideal medium for reflecting on and comprehending the truths of life. Indeed, the beauty of imagery stands as one of the most essential sources of artistic appeal in classical Chinese poetry.

The beauty of emotion

Ancient Chinese life teemed with the pursuit of poetic sentiment. It was on this cultural soil that the idea of shi yanzhi (poetry expresses one’s will) took root as the foundational principle of Chinese poetics. Later generations sometimes distinguished between shi yanzhi and shi yuanqing (poetry arises from emotion) as two different theories, but originally the meanings of will and emotion were essentially the same. As the Tang scholar Kong Yingda explained, “When emotion stirs within, it becomes will; emotion and will are one.” Thus, expressing one’s will is in fact what later generations called expression of emotion. The emotions expressed by ancient poets can roughly be divided into two major themes: renzhe airen (the benevolent love others) and tianren heyi (the unity of heaven and humanity). The first pertains to the social realm—an emotional flow directed inward toward humanity; the second belongs to the natural realm—a projection of human feeling onto the external world. Classical Chinese poetry gives profound expression to the idea of “the benevolent love others.” Among these expressions, love poetry occupies a particularly prominent place. Shijing begins with “Guanju,” perhaps symbolizing the importance of the love theme in the eyes of the ancients. The Tang poet Li Shangyin’s love poems rarely adopt the third-person narrative of Southern Dynasties folk songs, nor do they recount a complete story of love. Instead, they delicately portray the poet’s inner feelings, especially the pain of longing, rendering love with exquisite sensitivity and emotional depth—tender yet hauntingly beautiful.

The ideal of harmony between humanity and nature reflects the unique worldview of the ancient Chinese toward the natural environment. They believed that humans and nature stood not in opposition but existed in a relationship of harmony and mutual resonance. Nature was not only a physical space for dwelling but also a spiritual homeland. This deep emotional connection explains why the Chinese developed an early and profound appreciation for landscapes, giving rise to the flourishing of landscape poetry. Such poetry had already appeared no later than the Southern and Northern Dynasties, with Xie Lingyun of the Southern Dynasties honored as a “master.” Yet it was in the Tang dynasty that landscape poetry reached its zenith. The great Tang poets delighted in roaming through nature. From this tradition emerged the school of landscape and pastoral poetry in heyday Tang, with its most famous poets being Wang Wei and Meng Haoran. In their verses, landscapes of mountains, waters, and fields are both real scenes of nature and idealized homes of the soul.

The beauty of character

Classical Chinese poetry records the genuine inner voices of ancient writers and vividly conveys their outlook on life. From the poetry of China’s great ancient masters, we can glimpse the beauty of character in Chinese culture.

Qu Yuan, one of China’s earliest famous poets, was a “martyr” in the poetic realm. His Chuci, together with Shijing, stands as one of the two great sources of Chinese poetry. His noble and lofty personality and his unwavering patriotism have become an eternal model of moral integrity. Qu Yuan tirelessly sought the meaning of life, and though he ultimately ended his own life through the drastic act of drowning himself, he nonetheless achieved eternal life in spirit.

Tao Yuanming, the most renowned recluse of the poetic world, wrote in a plain and unadorned style. Though his poetry attracted little attention during his lifetime, his posthumous reputation grew steadily, making him a cultural giant deeply revered by later scholars. By choosing a life of seclusion and farming, Tao Yuanming embodied the ideal of contentment in simplicity, giving profound meaning to an ordinary life and proving that even a modest, humble existence can possess deep poetic beauty.

Li Bai was a free-spirited hero in the realm of poetry. Genuine and unrestrained, he fully embodied the romantic optimism and grand vitality of the flourishing Tang period. His poetry is passionate and bold, flowing like a mighty river, creating transcendent realms filled with wonder and imagination, and featuring an unbounded spirit of exploration.

Du Fu, by contrast, represented the Confucian scholar within the poetic world. Deeply devoted to the Confucian ideals of benevolent governance and compassion for the people, he made common suffering his personal concern. With his brush, he expressed a sober awareness of the nation’s hardships and the plight of its people. For his moral excellence and incomparable mastery of verse, he is venerated as the “Sage of Poetry,” a title that signifies the heightened realm of life he attained.

Su Shi was a veritable “lay Buddhist” in the realm of poetry. Deeply influenced by Confucian thought, he also absorbed the spirit of freedom and transcendence beyond worldly constraints from Daoism and Zen Buddhism. With resilience, open-mindedness, and a generous heart, Su Shi embraced life’s ups and downs, finding beauty and meaning in all things, completing a spiritual transcendence over reality.

Xin Qiji occupies a unique place in the poetic world as a hero-scholar with the bearing of a knight-errant. As a military poet, he infused a heroic spirit into the elegant realm of ci poetry, filled with a fervent sentiment of patriotic self-sacrifice, founding the powerful and heroic school in the ci arena. Reading Xin Qiji’s works can awaken one’s patriotic passion and evoke deep emotional resonance.

China is truly a nation of poetry, and Chinese civilization itself is a civilization of poetry. Poetry permeates every aspect of its cultural life, shaping the unique character of Chinese civilization. By reading classical Chinese poetry, we gain an ideal lens through which to experience the aesthetics of China, allowing the beauty of poetics to continually nourish the mind, spirit, and cultural refinement—becoming an ever-flowing source that fortifies the cultural foundation for building a strong nation and achieving national rejuvenation.

Mo Lifeng is a professor from the School of Liberal Arts at Nanjing University. This article has been edited and excerpted from Qiushi Journal, Issue 13, 2025.

Editor:yu-hui

Copyright©2023 CSSN All Rights Reserved