Realistic spirit endows Lu Yao’s creations with enduring vitality

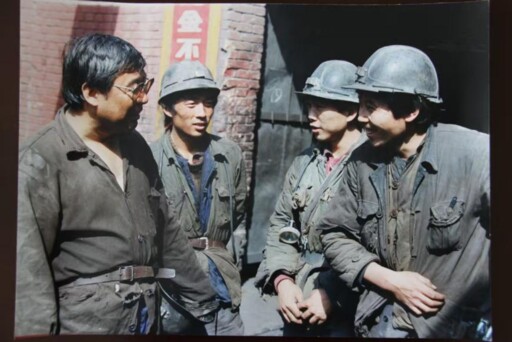

In-depth engagement: Lu Yao (first left) at the coal mines of Tongchuan, Shaanxi Province Photo: PROVIDED TO CSST

Lu Yao Photo: PROVIDED TO CSST

Thirty-three years have elapsed since the passing of writer Lu Yao in November 1992. Yet over the ensuing decades, his name has never receded from view, and his works—most notably the full-length novel Ordinary World—have continued to command a broad and lasting readership. The printed edition remains in steady circulation, while its television adaptation has likewise won wide acclaim. That a writer should retain such a vivid presence in the cultural imagination more than three decades after his death is, in itself, a rare phenomenon. Its deeper significance invites reflection on the essence of literary creation and on the enduring vitality of realism.

Lu’s literary success and the sustained appeal of his works arise from many personal and historical factors, but the most decisive lies in his unwavering commitment to realism and his principled innovation within that tradition. Because he adhered to a realist mode of writing, Ordinary World was initially overlooked by many and faced repeated obstacles in the search for publication. Yet precisely because he preserved the realist spirit, the novel later won the affection of a vast readership and became a perennial literary classic. The layered meanings embedded in this trajectory merit sustained reflection.

A rigorous realist writing method

In the early 1980s, Lu published the novellas A Shocking Scene and In the Difficult Days. Though grounded in ordinary subject matter, these works display an intense concern for human destiny and evoke a complex, painful emotional resonance, bearing a pronounced realist quality. His 1982 novella Life proved even more striking. It not only elevated Lu’s depiction of life in the urban-rural borderlands to a new level, but also endowed the narrative with openness and complexity through the protagnist’s inner conflicts and difficult choices. If these works exemplify a rigorous realist technique, then the novel Ordinary World may be regarded as the culmination of Lu’s realist practice.

Engels once offered a classic formulation of the realist method: Realism, he argued, requires not only truth in detail, but also the truthful representation of typical characters in typical circumstances. This formulation contains two core requirements—faithfulness to detail and the creation of representative characters within representative environments—which together constitute the basic elements of realist literature.

Lu clearly grasped the essence of this method. From the outset of his literary career, he rigorously upheld the realist demands of “truthful detail” and typified the “creation of typical characters in typical circumstances.” During the 1980s, as new literary concepts and techniques swept through China’s literary circles, Lu—then immersed in the writing of Ordinary World—remained notably calm and unswayed. He even remarked that “many works created using so-called realist methods actually diverge greatly from the spirit of realist literature.” Holding fast to his convictions, he persisted in his pursuit and, with almost paradigmatic determination, completed the three-volume Ordinary World.

In writing Ordinary World, Lu emphasized the authenticity and vividness of everyday detail, while paying particular attention to the interconnections between individuals, their environment, and their historical moment. By portraying how two rural young people—Sun Shao’an and Sun Shaoping—struggle through hardship to take control of their destinies, the novel captures social transformation, historical change, and the close entanglement of personal fate with national destiny. Emerging from situations of near powerlessness and despair, the protagonists encounter the invigorating momentum of reform and opening up, seize the opportunities of the era, and begin to reshape their lives. Sun Shao’an turns to household contracting and establishes a brick kiln, repeatedly rising after setbacks; Sun Shaoping becomes a factory worker and, through diligence and helpfulness, grows into an exemplary one. The novel also incorporates major historical events, including Chairman Mao’s passing, the convening of the Third Plenary Session of the 11th CPC Central Committee, and the land-contract reform in Xiaogang Village, Anhui Province. These moments function both as lived experiences of the characters and as faithful records of history. Through a northern village and two rural young people, Lu artistically reproduces the profound changes in rural society and the evolving spiritual outlook of farmers in the early years of reform and opening up. By foregrounding the interaction between individual destiny and historical forces, his fiction decisively transcends the conventional boundaries of rural-themed literature. At the same time, his protagonists are endowed with a distinctive inner strength—a tenacious resolve to press forward and a determination to take their fate into their own hands.

A full, vigorous realist spirit

Lu’s fiction not only rigorously employs realist techniques, but also embodies a full, vibrant realist spirit. This realist spirit bears his distinctive personal stamp—namely, his strong emphasis on the people and on human subjectivity.

At the heart of the realist spirit lies a commitment to the human being: an insistence on centering literary creation on people’s living conditions, mental states, and destinies, and on placing the people themselves at the core of representation. In practice, this means treating ordinary people as the protagonists of artistic expression, pouring their joys and sorrows onto the page. At the same time, realism requires writers to confront life with sincerity and to heed their inner moral compass. The projection of the writer’s own subjective force thus becomes crucial. Without sufficient inner strength or spiritual depth, a work’s own spiritual richness will inevitably be constrained. In this sense, a writer’s intellectual and moral resources determine the spiritual depth of the work, and the vitality of realism ultimately rests on the writer’s own subjective spirit.

In Ordinary World, the realist pursuit that Lu had demonstrated from A Shocking Scene to Life—his commitment to staying closely attuned to the times, portraying ordinary people, remaining close to the people, and speaking on behalf of the broader public—not only remains intact, but is in fact significantly deepened. This is apparent in his effort to interweave concise sketches of major historical events with finely textured depictions of everyday life, revealing both the great surges and the subtle undercurrents of history. It is also evident in his deliberate and distinctive use of the pronoun “we.” Throughout the novel, “we” repeatedly appears, blending a first-person sensibility into a third-person narrative. This device places the author naturally among the community of characters while simultaneously drawing readers into the narrative world. Author, reader, and character are subtly aligned within the same process of living and reflecting, forming a shared community of fate. The recurring “we” in Lu’s work thus serves both as an expression of his closeness to his characters and as a manifestation of his self-effacing immersion in the collective. It makes unmistakably clear Lu’s aspiration to speak and advocate for ordinary people, and reveals his realist stance of viewing life through the lens of the people themselves to portray human experience through their sentiments.

Resonating spiritually with broad readership

In Lu’s work, realist technique and spirit merge into an organic whole, forming a distinctive literary style. The close intertwining of the individual and the era is reflected in the lived conditions of ordinary people, the struggles of those who strive forward, and the renewed efforts of those who have suffered setbacks. What Lu writes about is precisely what readers have experienced—or what they seek to understand. Thus, from the outset, the “supply’ and “demand” of literature align, making the widespread resonance of his works both natural and enduring.

At the beginning of the 1988 China National Radio broadcast series of Ordinary World, a brief voice-over by Lu himself—in which he articulated his original intention in writing the novel—helps explain its lasting appeal. He remarked:

“Personally, I believe this world belongs to ordinary people. The world of ordinary people is, of course, a plain and unadorned world, yet it is forever a great world. As a laborer in this world, I will always regard the world of ordinary people as a sacred deity of my creation. Dear listeners, no matter how many difficulties, pains, or even misfortunes we encounter in life, we still have reason to feel proud of the land and the times in which we live!”

After Ordinary World won the Mao Dun Literature Prize, Lu made a special trip to Huangfu Village in Chang’an County (in present-day Xi’an, Shaanxi Province) to pay tribute at the tomb of Liu Qing. Choosing this setting for an interview, he expressed gratitude to his literary mentor and paid homage to a master of realist literature. Following in Liu Qing’s footsteps, Lu carved out his own creative terrain within the realist tradition, developed a distinctive literary voice, and achieved remarkable success. This trajectory points to a broader critical task: the need to reexamine realism—not only its connotations, extensions, methods, and spirit, but also its deep ties to Chinese literary tradition and its enduring connection with Chinese readers. Literary creation grounded in realist technique and animated by a realist spirit is not only demanded by its era, but also embraced by readers, and thus possesses broader influence and lasting vitality.

Bai Ye is a research fellow from the Institute of Literature at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

Editor:yu-hui

Copyright©2023 CSSN All Rights Reserved