Hou Renzhi and the modernization of historical geography

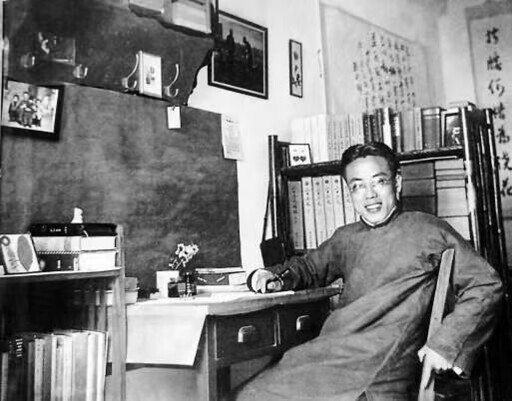

File Photo: Hou Renzhi

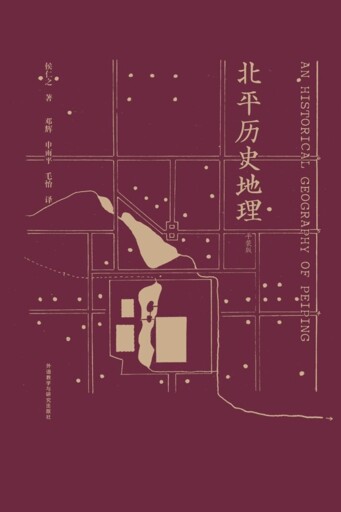

File Photo: A Historical Geography of Peiping

File Photo: Living Memory of Beijing City

Hou Renzhi (1911–2013), born in Zaoqiang County, Hebei Province, with ancestral roots in En County, Shandong Province, was a leading historical geographer in modern China. Throughout his life, he pursued scholarship with rigor and imagination, making enduring contributions to the transformation of the discipline from “traditional historical geography” to “modern historical geography.” His academic career stands as a key chapter in the modernization of Chinese historical geographical studies.

Passing on academic thought

Since the late Qing period, the steady introduction of Western academic ideas prompted sustained change within Chinese historical geography, even as it continued to draw on its own fine traditions. As a branch of traditional history, evolutionary geography likewise underwent gradual but significant transformation. In the 1930s, while studying at Yenching University, Hou was firmly grounded in this tradition while also participating actively in the broader project of academic modernization.

Hou’s initial understanding of historical geography was rooted in traditional historical geography, while his intellectual lineage was shaped by eminent historians such as Hong Ye and Gu Jiegang. Under Hong’s supervision, he received exceptionally rigorous training in historical methodology and also attended Gu’s course “The History of Ancient Chinese Historical Geography.” Through this training, Hou gained a preliminary grasp of the core concerns of traditional historical geography, including place-name verification, river course changes, and fluctuations in territorial boundaries.

In early 1934, Gu initiated the establishment of the Yugong Society and founded the semi-monthly journal Chinese Historical Geography. Hou joined the endeavor soon afterward. Judging from the journal’s inaugural foreword and its early articles, Gu and his colleagues not only emphasized the close relationship between history and geography but also broadened the scope of historical geography to include natural, economic, and borderland geography. Immersed in this intellectual environment, Hou began to develop his own reflections on the relationship between history and geography.

With Hong as his guide, Hou was also introduced to the works of Gu Yanwu, a late Ming–early Qing scholar whose emphasis on jingshi zhiyong (经世致用)—the application of learning to practical affairs—had a lasting influence on him. Hou’s master’s thesis, “Continuation of Treatise on the Advantages and Disadvantages of the Commanderies and States of the Empire: The Shandong Section,” moved beyond mere historical annotation to incorporate real-world social concerns into academic inquiry. This orientation toward practical relevance gradually crystallized into Hou’s enduring scholarly commitment and later became a driving force behind his efforts to reshape the discipline.

In 1938, Hong encouraged Hou to specialize in geography and recommended that he study under the renowned geographer Percy Maude Roxby at the University of Liverpool in the United Kingdom. The outbreak and expansion of the Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression, however, brought these plans to a halt. Only in 1946 did Hou regain the opportunity to study in the UK again, where he pursued doctoral training under Sir Henry Clifford Darby, head of the Department of Geography at the University of Liverpool and one of the founders of modern historical geography. Darby’s advanced understanding of the discipline enabled Hou to acquire, within a relatively short period, a far more systematic and modern conception of historical geography.

Hou’s precise grasp of disciplinary nature, research materials, and methodological approaches found its most concentrated expression in his doctoral dissertation, “The Historical Geography of Peiping.” Using a cross-sectional reconstruction method, he divided the city’s development into three major stages—“frontier city,” “transitional phase,” and “dynastic capital”—and traced the changing political status of the city across time. From the perspective of disciplinary history, this work was the first urban historical geography study independently completed by a Chinese scholar in accordance with the paradigm of modern historical geography. It thus occupies a landmark position in the development of the field and signaled that Hou had already reached the forefront of disciplinary innovation and glimpsed its future directions.

Initiating disciplinary transformation

After the founding of the People’s Republic of China, Hou politely declined Darby’s invitation to remain in the United Kingdom and conduct research, choosing instead to return home. At a time when newly established institutions of higher education urgently needed to advance modern disciplinary construction, Hou quickly recognized persistent shortcomings in existing courses on “traditional Chinese historical geography.” In response, he published the article “On the ‘Chinese Historical Geography’ Course,” in which he explicitly called for curricular reform and disciplinary transformation.

Hou argued that reform should go beyond renaming the course—from “Chinese Evolutionary Geography” to “Chinese Historical Geography”—and extend to a thorough reorientation of its content. Taking Beijing as an example, he pointed out that traditional studies focused primarily on changes in administrative divisions offered little practical insight into the development of the contemporary metropolis. Instead, he contended that teaching and research should concentrate on transformations in the geographical environment across historical periods, thereby breaking decisively with the conceptual confines of traditional evolutionary geography. This proposal marked a clear intellectual rupture with earlier approaches and reflected the maturity of Hou’s understanding of historical geography.

During this period, dialectical materialism played a crucial role in shaping Hou’s views on core issues such as the relationship between humans and the environment. It enabled him, at a theoretical level, to recognize the dialectical interaction between human society and geographical conditions, thereby rejecting the deterministic separation of “geographical environment” from “humans and history.” At the same time, it reinforced his emphasis on human agency in historical struggles with nature, further underscoring the broader significance of historical geography as a field of inquiry.

Hou’s understanding of the discipline did not immediately command universal agreement within the academic community. Aware of this, he published another essay, “Humble Opinion on Historical Geography,” in which he carefully distinguished historical geography from traditional evolutionary geography and offered a systematic exposition of the field’s disciplinary attributes and research scope. He argued that historical geography belongs firmly within geography as a discipline, and that its central task lies in reconstructing past geographical environments, identifying patterns of geographical change, and explaining the formation and characteristics of present-day landscapes. These clarifications helped consolidate scholarly consensus and significantly accelerated the discipline’s transformation.

Shouldering responsibility through practice

Following the establishment of the PRC, debates over the nature, content, and methods of historical geography unfolded alongside a growing emphasis on ensuring that academic research served production and national construction. Hou’s accurate positioning of the discipline facilitated the expansion of research practice, which in turn deepened his understanding of historical geography and contributed to its institutional development.

Hou’s research on urban historical geography, with Beijing as a representative, during the 1950s offers a particularly compelling illustration. Shortly after his return to China, the architect Liang Sicheng posed a pointed question to him: “What can your research on historical geography do for Beijing?” Hou pursued this question persistently, and his subsequent scholarship provided a substantive answer. His article on the “Topography, Waterways, and Settlements in the Vicinity of Beijing’s Haidian District” offered valuable reference points for planning the capital’s cultural and educational districts, while his article “The Water Source Problem in the Development Process of Beijing City” proposed feasible solutions to pressing practical problems. Through the efforts of Hou and his contemporaries, historical urban geography emerged from obscurity, gaining recognition for both its academic rigor and practical relevance.

From the 1960s onward, Hou’s engagement with historical desert geography further solidified his reputation and exemplified his commitment to advancing the discipline through practice. Responding to the national call to “march into the deserts,” he led research teams into areas such as the Heda Desert in Ningxia, the Ulan Buh Desert, and the Mu Us Sandy Land. These investigations yielded a series of important findings, including the methodological insight that the spatial distribution and rise-and-fall cycles of ancient city sites could serve as indicators of environmental change in arid regions. This work not only opened new research directions for historical geography in China but also laid a firm theoretical foundation for subsequent studies. Under the impetus of scholars such as Hou, subfields including historical desert geography and historical urban geography developed rapidly, and the overall disciplinary system of historical geography was progressively enriched and refined.

Through a continuous movement from practice to reflection and then to more advanced forms of practice, Hou played a decisive role in guiding the transformation from traditional evolutionary historical geography to modern historical geography. The successfully transformed discipline, distinguished by its integration of scholarly depth and practical relevance, subsequently entered a period of sustained growth and vitality.

Ma Zhouqun is a lecturer from the School of Marxism at Shandong University of Technology. Li Lingfu is a professor from the Northwest Institute of Historical Environment and Socio-Economic Development at Shaanxi Normal University.

Editor:Yu Hui

Copyright©2023 CSSN All Rights Reserved