Appreciating and promoting public philosophy

Author : WANG YOURAN Source : Chinese Social Sciences Today 2022-02-11

Since the millennium, there has been a steady increase in the visibility of philosophy in public life, both online and offline. Apart from books on philosophy, there are online courses, television and radio programs, newspaper columns, podcasts, and live events. Philosophy today is just as likely to be found on popular websites as it is in a bookshop or library.

Many public-oriented philosophy “products” are very popular. Just to mention a few: “Justice,” an online course lectured by Harvard Professor Michael J. Sandel; “A History of Ideas” and “In Our Time,” both cultural programs produced by BBC 4; “History of Philosophy Without Any Gaps,” a podcast hosted by Peter Adamson, a professor at LMU Munich; “Philosophy Bites,” a BBC podcast series which interviews philosophers. Those “products” are generally classified as practices of public philosophy.

Engaging with the public

Public philosophy is understood to be activities, varying in format and purpose, undertaken by academic philosophers that are intended to bring philosophy into contact with the general audience, observed Justin Weinberg, who serves as an associate professor of philosophy at the University of South Carolina and runs the professional philosophy news site Daily Nous. In short, public philosophy aims to explore and embody philosophy’s value to the public.

Public philosophy is directed at the general public rather than academics. “Any piece of work that deals with philosophy through popular forms can count as public philosophy,” said Greg Littmann, an associate professor of philosophy at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville. The tradition of public philosophy is an ancient one. Philosophers from ancient times till now have been involved in public philosophy, even if they don’t necessarily call it “public philosophy.” In the last twenty years, the philosophical community has increasingly begun to recognize the importance of public philosophy and encouraged philosophers to get involved.

Not “beside the point”

Some academic philosophers consider engagement with the public a digression from work more useful to philosophy, a waste of time, or an activity of inferior “intellectual value.” In other words, they believe philosophical work ought only to be useful for philosophers and the field itself. Public philosophy is therefore “beside the point.” If the “usefulness” of philosophy is, in part, an empirical question, to whom philosophy should be “useful” is an evaluative question that is more difficult to answer.

Brian Leiter, a professor of jurisprudence and director of the Center for Law, Philosophy and Human Values at the University of Chicago, once made the remark that the likelihood of interesting philosophical insight provided by an ordinary person without advanced and specialized education is probably pretty limited, though what ordinary people think is often the data point philosophers are interested in. This may sound offensive to some, but Leiter sees himself as defending the concept of “expertise.” Philosophers are trained to engage in philosophy just as building engineers are trained to build bridges. Since non-engineers are not qualified to build a bridge, people should not expect non-philosophers to speak eloquently about philosophy.

Leiter’s remark is justifiable in terms of division of labor and specialization. However, building bridges is a task exclusive to engineering professionals, while philosophical thinking and judgment is omnipresent, sometimes with significant consequences. For instance, people resort to logic to determine the best means to an end and evaluate the possible consequences of an action; they take ethical concerns into account in their decision-making, and make use of aesthetic knowledge to assess the quality of cultural and artistic products. It’s obvious that people without specialized training in philosophy are unlikely to be recognized by the philosophical community for their contribution to the discipline. However, it doesn’t mean that they can’t come up with meaningful, sophisticated, even novel philosophical ideas.

Democratic theory presupposes the philosophical and rational capacities of the general public, including the ability to make complex moral and political judgments, and the meta-level skill of reflecting on and evaluating one’s own rationality, noted Jack Russell Weinstein, a professor of philosophy and director of the Institute for Philosophy in Public Life at the University of North Dakota.

The “capability approach” proposed by Amartya Sen, a professor of economics and philosophy at Harvard University, and Martha Nussbaum, a professor of law and ethics at the University of Chicago, gives credit to everyday intellect. Its focus is on what individuals are capable of, rather than mere rights or freedom. If we claim that non-philosophers are completely philosophically incapable, we have to give up on democracy.

In Littmann’s opinion, the significance of public philosophy rests in the fact that philosophers must share their ideas in order to benefit the public. Unlike science, philosophy can’t be of use to people who don’t understand it. Moreover, the questions philosophers try to answer are often questions that everyone is curious about, such as “what are my moral duties,” “is there a God,” and “what is the best political system.”

Public philosophy will become much more important in the post-pandemic era, as the public has shown great interest in public philosophy and academics are responding to that need by producing more, Littmann said.

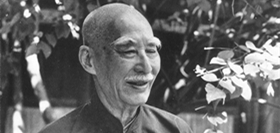

Ye Shengtao made Chinese fairy tales from a wilderness

Ye Shengtao (1894–1988) created the first collection of fairy tales in the history of Chinese children’s literature...

-

How northern ethnicities integrated into Chinese nation

2023-09-18

-

Mogao caves

2023-09-12

-

Mogao Grottoes as ‘a place of pilgrimage’

2023-09-12

-

Time-honored architectural traditions in China

2023-08-29

-

Disentangling the civilizational evolution of China

2023-08-28

-

AI ethics in science fiction

2023-08-23

2011-2013 by www.cssn.cn. All Rights Reserved

2011-2013 by www.cssn.cn. All Rights Reserved